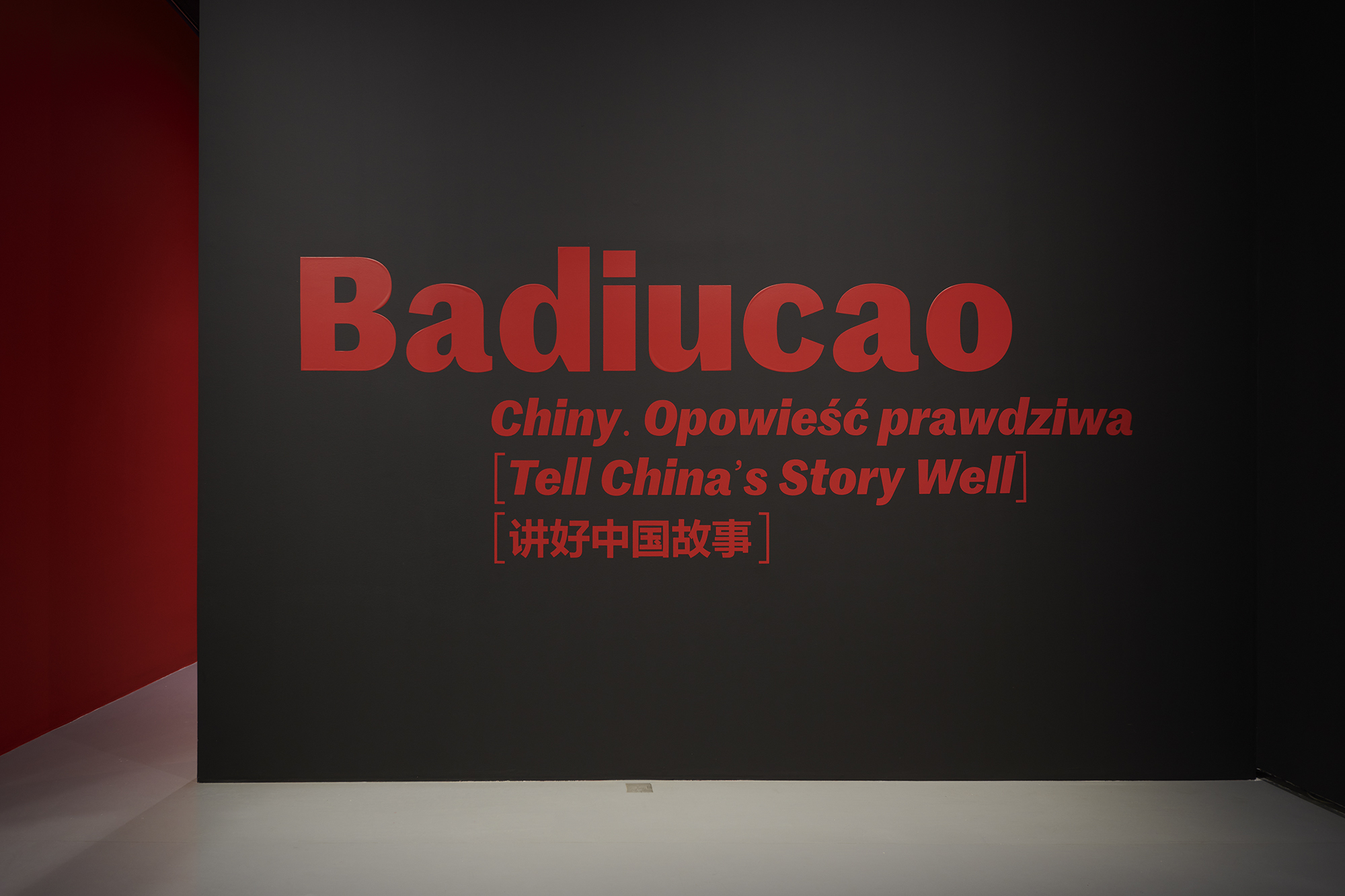

The article introduces the work of Chinese dissident artist Badiucao, whose exhibition was held at the Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw last year[1]. Titled 'Tell China's Story Well', the exhibition referred to an official Chinese Communist Party (CCP) propaganda slogan. It was an ironic portrayal of the Middle Kingdom as it is, rather than as conveyed by official propaganda. The repression of the artist and his art by the authorities of the People's Republic of China (PRC) is linked to the position of the Party and its approach to governance. Citizens of Western democracies hardly understand a Far Eastern country that differs from us in almost everything: value system, political understanding, culture, language and writing. It has thus become an important game, with the Asian superpower's position in the modern world at stake, to provide the West with an adequate narrative of Chinese history.

Badiucao. Artist on Duty

The day following the official announcement of the Badiucao exhibition at the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, a high representative of the Chinese Embassy visited the the institution, demanding a meeting with the director. The subject was an explicit demand to cancel the exhibition, which, according to the diplomat, could have a negatively impact on Polish-Chinese relations. Similar demands were made to the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage. It was the first time in the Centre's history that a foreign representative attempted to directly influence the institution's programme.

The embassy's strong reaction is in line with the Chinese government's strategy of presenting a single official narrative about China. This narrative is at odds with the narrative of Badiucao's art. In what follows, I'll try to identify the fundamental causes of this incompatibility between the two visions - the official one and the completely different one - based on the experience of an artist who was forced to flee his country. This should help us to understand the significance of Badiucao's art, which is an attempt to translate the way the People's Republic of China functions into a language comprehensible to a Western public.

Baduciao is a Chinese-born artist and activist fighting against censorship and the current political system in the Middle Kingdom. Faced with the threat of repression against him and his family, he settled and worked in Australia. At the beginning of his artistic career, he was a meme artist. Today, he works in a variety of media: through painting, drawing, performances and actions in public spaces, the design of neon signs and the use of ready-mades. The exhibition at the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art was Badiucao's fourth attempt to have his work on display in a gallery space. The Chinese artist's first exhibition was due to open in Hong Kong in 2018. It was cancelled for security reasons after the artist received threats from the Chinese authorities[2]. Despite a letter of protest from the Chinese Embassy to the director of the institution, he managed to present the exhibition in 2021 at the Civic Museum in Brescia, Italy[3]. The same thing happened a year later with the next edition of the exhibition at the DOX Centre for Modern Art in Prague[4].

When we began preparations for the Badiucao exhibition in Warsaw, we had reason to fear that the planned exhibition would also be opposed by the Chinese authorities[5]. Following the diplomat's visit, the Director decided to issue a statement unequivocally condemning the Chinese authorities for what happened. The statement called the diplomat's visit an attempt to impose preventive censorship, incompatible with the standards of a democratic country. It also referred to the English title of the exhibition, "Tell China's story well". The director pointed out that Badiucao's artistic narrative about China differs from that presented by official Chinese propaganda. He concluded the statement with an appeal to all those who are interested in the struggle for freedom of speech and freedom of artistic expression to attend the exhibition.

Badiucao. Tell China’s Story Well, Exhibition at the Center for

Contemporary Art, Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw , Photo by A. Gut

Tell China’s Story Well

The title of the exhibition, "Telling China's story well", was an ironic reference to the propaganda strategy adopted by the PRC following Xi's appointment as General Secretary[6]. Its primary goal is changing the public image of China in the West. China was to open up to the West and become a benchmark for setting global standards in technological development, entrepreneurship and governance, rather than being perceived as a country with socio-economic problems. Conceived as a multidimensional shift in the perception of China, the propaganda campaign focused on two levels. The first, described as 'new ways of expression' (pinyin xin biaoshu), is based on the assumption that stereotypes and a lack of understanding of the mentality of the people of the Middle Kingdom are at the root of Western societies' negative view of China. In response, xin biaoshu focuses on showcasing the originality and significance of Chinese cultural achievements. One of the most important tools for the dissemination of knowledge about the country is the pinyin, the official transliteration of Chinese terms into the Latin alphabet. The Chinese are keen to ensure that the meanings of expressions from their language that reach the West remain as unaltered as possible, which is why they encourage the use of pinyin rather than transcription. Transliteration gives the Chinese more control over how their country is portrayed.

The speeches of Chinese politicians and experts presented in the media are another way in which 'new forms of expression' are disseminated. These include historical references to great chapters in Chinese history, invoking thinkers such as Confucius, and pointing to Chinese achievements in solving economic and social problems. In the first place, the speeches available in the Western media promote China to a foreign audience. Secondly, they have an impact on the party's internal image through the portrayal of China as a major player in the geopolitical arena.

There are two forms in which another dimension of the Middle Kingdom's propaganda strategy manifests itself: "new categories" (pinyin xin fanchou) and "new concepts" (pinyin xin gainian). The former involves using concepts specific to liberal democracy, such as 'rule of law', 'globalisation', 'terrorism' and 'democracy', while changing their original meanings. Liberal notions of democracy include not only electing political agents but also procedures and measures to ensure security for minorities not represented by winning political parties. In Chinese socialist democracy (pinyin shehui zhuyi minzhu), the choice is limited to a single Communist Party, and the political balance is achieved through competition between the internal factions. The lack of free choice for the electorate is explained by the establishment of a control system that denies the danger of populism that the Chinese authorities accuse Western democracies of. Similarly, China's propaganda uses other well-known concepts of social thought and understands them in a way that completely distorts their commonly accepted meaning in the West.

The other form is ‘new concepts’ (pinyin xin gainian), which is the creation of ideas based on an Eastern system of thought that is peculiar for China. These are then disseminated across borders as alternatives to dominant Western discourses. In the face of escalating global problems, Asian countries, including China, are proposing their own solutions. In the case of the Middle Kingdom, these are collectively referred to as 'Chinese solutions', which conceal much more detailed ideas.

One example is the 'community of shared destiny' (pinyin zhengque yili guan), which is seen as a response to Western globalisation. In doing so, China projects itself as a country that protects those who have been, or continue to be, victimised by Western hegemony. The propagandistic dimension of this concept involves shifting the focus from business and the desire for unlimited profit, which supposedly characterise the United States, to basing international relations on morality and justice (derived from ancient Chinese philosophy - the thought of Confucius and Mencius). According to this, under the ideological leadership of the Communist Party of China, a global balance of interests and a peaceful co-existence of states is possible.

Warsaw Proposal from Badiucao

In his exhibition in Warsaw, Badiucao presented his own interpretation of the slogan "Tell China's Story Well", referring to the following themes explored in the exhibition: "Artist on Duty", "Power Challenge", "Wuhan Diary", "Faded and Forgotten", "Voice of Protest", "The Art of Measuring Pain", "Ukraine" and "Tribute to Resistance".

"Artist on Duty" focused on the artist's relationship with the Chinese authorities. The opening of this exhibition was a portrait of another artist-activist, Ai Weiwei, an icon of the struggle for freedom of expression and human rights in China. This was a clear reference to the ideological patron of both this exhibition and other activities undertaken by Badiucao.

Badiucao. Tell China’s Story Well, Exhibition at the Center for

Contemporary Art, Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw , Photo by A. Gut

Throughout the first part of the exhibition, we also saw masks hanging on mirrors. These were successive manifestations of the artist's alter ego - used during the period when he was forced to hide his identity completely. Here we enter a reality in which Badiucao's 'self' - as a Chinese citizen, artist and human being - is subordinated to the duty of resisting his own government's policies. This is also indicated by the object bed, which has been scratched with sharpened pencils like a procrustean bed. That work of art can be understood as an expression of the duty that is imposed on the artist, who must always be prepared to stand up for his or her own convictions.

Badiucao, Tiger Chair,

Exhibition Tell China’sStory Well at the Center for Contemporary Art,

Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw , Photo by A. Gut

A significant artwork in this part of the exhibition was „The Tiger Chair” (2018). This authentic piece of furniture, used by the Chinese authorities for interrogation and torture, was purchased by the artist at an online auction. After several modifications, the object was presented as a ready-made. The work of art makes a direct reference to the activities of the Chinese authorities, which violate the most elementary rules of a fair trial. At the same time, as if in a distorting mirror, it repeats Marcel Duchamp's gesture. Whereas the ready-mades of the Dada classic were a perverse critique of the institutional artworld, the Tiger's Chair is an uncanny update of this action. The object is an allusion to the artist's obligation to confront the socio-political reality of his surroundings.

Badiucao. Tell China’s Story Well, Exhibition at the Center for

Contemporary Art, Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw, Photo by A. Gut

The next part of the exhibition was filled with satirical images of the General Secretary of the CCP, as a symbol of resistance to the Chinese government. In China, it is strictly forbidden to display mocking images of Winnie the Pooh. The friendly character from the children's cartoons is functioning in the memosphere as a symbolic representation of Xi Jinping because of his distinctive appearance. This section of the exhibit also featured artistic commentary on the actual legacy of the General Secretary. This was demonstrated by a painting showing the Chinese leader resurrecting the body of Mao Zedong.

A major theme of the exhibition was the Covid-19 pandemic. One of the paintings pays tribute to Dr Li Wenliang, who was among the first to warn the public about the new, potentially dangerous virus[7]. However, the doctor was imprisoned and forced into self-criticism. Shortly afterwards, he himself contracted the virus and died of severe respiratory failure. He was rehabilitated by a Chinese court after his death and hailed as a hero under public pressure.

Badiucao. Tell China’s Story Well, Exhibition at the Center for

Contemporary Art, Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw, Photo by A. Gut

The cynical use of the pandemic by the Chinese authorities to control society was highlighted in other works in the exhibition. Initial attempts to ignore and mute the problem were followed by a period of radical control of the outbreak. This was done with a total disregard for basic civil rights. People were confined to their homes. There were cases of death and mental illness caused by a state of prolonged isolation and functioning in a situation of constant threat[8]. This is referred to in the “Wuhan Diary” (2020) - the anonymous notes of a person who has experienced life in a city isolated by the authorities - which was given directly to Badiucao and included as a work of art in the exhibition.

The following two thematic sections: 'Faded and Forgotten' and 'Voice of Protest', commemorated events that Chinese propaganda has tried to erase from the Middle Kingdom's recent history. A very touching work was „This is Why They Buy Our Baby Formula” (2018). Featuring images of infants covered in powdered milk, the installation referred to the 2008 scandal in which several children died and thousands were hospitalised after consuming milk contaminated with the highly toxic chemical melamine[9]. Since then, China has seen similar situations involving the consumption of toxic baby food.

Other works in this section deal with sensitive issues suppressed by China's official narrative. These include the Uighur genocide - a forced assimilation of a Muslim ethnic minority. More than a million residents of Xinjiang Province were imprisoned without trial in re-education camps. Further artworks addressed the plight of the persecuted people of Tibet and paid tribute to the Tibetans who have set themselves on fire in protest at the repression of the Chinese authorities. Many of the works in this part of the exhibition used symbols of well-known clothing and media brands. This was a nod to the PRC's links with the big, global business world.

Badiucao. Tell China’s Story Well, Exhibition at the Center for

Contemporary Art, Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw, Photo by A. Gut

The focal point of the exhibition was a monumental portrait of Mao Zedong, a replica of the image displayed in Tiananmen Square in Beijing. At a press conference prior to the exhibition's opening, the artist staged a performance in which he pelted the portrait with eggshells filled with coloured ink. The action was a reference to the events of 1989, when mass protests against the authorities took place in the PRC capital. In one of the incidents, three demonstrators threw eggs filled with ink at a portrait that was towering over the square. The three - Yu Dongyue, Lu Decheng and Yu Zhijian - were arrested and sentenced to lengthy prison terms. They remain symbols of resistance to authority for those fighting for human rights in China. Badiucao's performance was an homage to the protesters' heroism and a symbolic climax to their gesture.

Badiucao. Tell China’s Story Well, Exhibition

at the Center for Contemporary Art,

Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw, Photo by A. Gut

The Tiananmen Square tragedy was also alluded to in another work in the exhibition, an installation of dozens of cubes containing drawings in the artist's blood. The coagulated spots formed shapes that resembled clocks and watches. The artwork was a reference to the commemorative watches given to officers in recognition of the party's violent suppression of demonstrations. The inscription on each watch was ”89.6 - in commemoration of the suppression of the rebellion” in Chinese. Over time, the authorities realised the watches were inconvenient evidence and demanded their return. Some of the items were able to be salvaged, and Baduciao has come into possession of one of the watches and has incorporated the case into his exhibition.

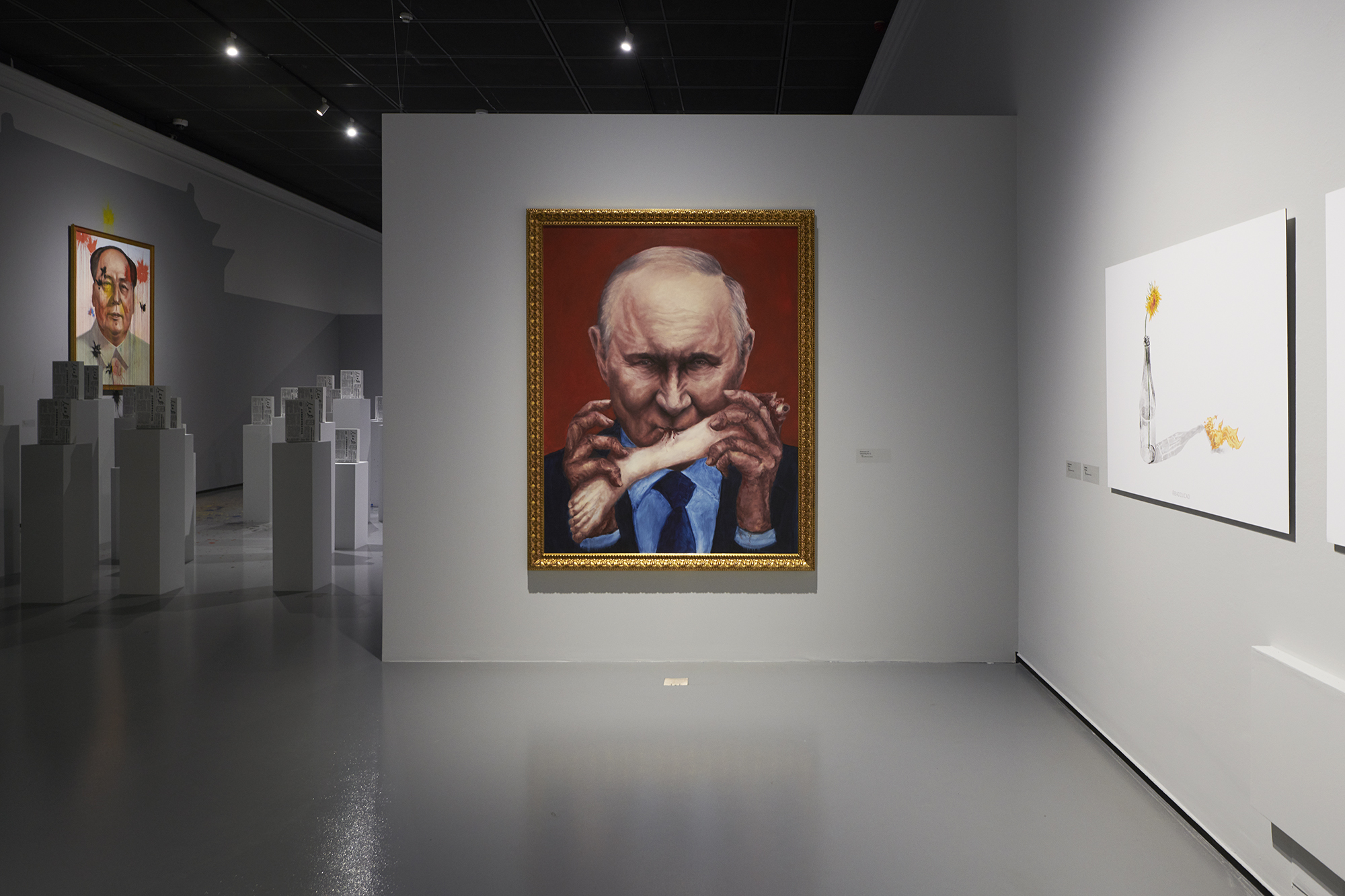

Badiucao, Devouring No. 2,

Exhibition Tell China’s Story Well at the Center for Contemporary Art,

Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw, Photo by A. Gut

The European context of the exhibition is introduced by a section entitled 'Ukraine', which brings together works that refer to the relationship between China and Russia. The paintings, which allude to Francisco Goya's „Saturn devouring his own children”, show Putin and Xi Jinping destroying their potential successors, turning themselves into parasites exploiting their own countries.

Badiucao, Tribute to Resistance,

Exhibition Tell China’s Story Well at the Center for Contemporary Art,

Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw , Photo by A. Gut

The exhibition closed with a ”Tribute to Resistance”, consisting of just two elements: a monumental neon sign and a sound installation. Again, the reference to Goya's classic painting 'The Shooting of the Madrid Insurgents' is significant. In Badiucao's version, made as a neon sign, the building from the Spanish painter's canvas is replaced by the contours of an architectural hybrid of Beijing's Tiananmen Gate and Moscow's Kremlin. Towering over the scene is an inscription in Chinese. One of the students who took part in the protest, when asked by a journalist about the reasons for his resistance, replied: "It's my duty". Recalling the events of 1989, this phrase became a slogan of rebellion against authority. Badiucao uses it to crown his monumental neon sign and in the sound installation, a collection of voices repeating "It's my duty".

Badiucao, Tribute to Resistance,

Exhibition Tell China’s Story Well at the Center for Contemporary Art,

Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw , Photo by A. Gut

Badiucao's role in his exhibitions goes beyond presenting interesting works of art. The exhibition allowed us to see China from a perspective that has been erased by the authorities. Through his work, the artist takes on the role of an interpreter, in an attempt to familiarise and explain a reality that is inaccessible to us. Using the language of contemporary art, he has to convey the truth. In doing so, he is competing with a state whose propaganda machine creates a completely different vision of China's history. This is even at the cost of the suffering of its own citizens.

[1] The exhibition "Badiucao Tell China's Story Well" was on display from 16 June to 3 December 2023. It was curated by Michaela Šilpochová.

[2] See: Chinese dissident Badiucao's Hong Kong show cancelled over 'threats', published 3 Nov. 2018 at www.bbc.com, (accessed 29.02.2024).

[3] See: E. Povoledo, The Show Goes On, Even After China Tried to Shut It Down, published 12 Nov. 2021 at www.nytimes.com, (accessed 29.02.2024).

[4] See: K. Brown, China Tried to Shut Down Dissident Artist Badiucao’s Show in Prague. It Only Made Him More Famous, published 13 May 2022 at www.news.artnet.com, (accessed 29.02.2024).

[5] The author of this text is an employee of the Centre for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle, involved in the organisation of the Warsaw exhibition.

[6] The description of China's propaganda strategy is based on: J. Szczudlik, 'Tell China's Stories Well': Implications for the Western Narrative, in Policy Paper, No. 9 (169), September 2018, online: at www.pism.pl, (accessed 29.02.2024).

[7] See: Li Wenliang: 'Wuhan whistleblower' remembered one year on, pubished 6 February 2021 at www.bbc.com (accessed 29.02.2024).

[8] See: H. Markel, Will the Largest Quarantine in History Just Make Things Worse?, published 27 January 2020 at www.nytimes.com, (accessed 29.02.2024).

[9] Por. A. Jacobs, Chinese Release Increased Numbers in Tainted Milk Scandal, published 8 December 2008 at www.nytimes.com, (accessed 29.02.2024).