Senghor needed both the soil and the stone in order to be able to create a physical frame, to envelop his thinking. In the early 1960s, he chose three strategic locations. Let us take a brief moment to look at these locations, which have connected us with Léopold Sédar Senghor by an unbreakable bond.

“When will the year 2000 come?” This question was asked by a friend of mine from high school, while he was looking from afar at a large billboard towering over Independence Square; it painted a rosy picture of Dakar in the future. However, neither Voltaire nor Rousseau was to blame. It was Senghor’s fault [1]. This wily statesman managed to sow the seeds of doubt in our urchin minds; we the survivors of the May 1968 protests in France. Thus, he managed to replace the ideals of the time such as class conflict, the proletariat, Communism, the Cold War, and Capitalism, with milder synonyms, softer and less alarming in tone, more human and essentially in-line with our Negro concerns (émoi nègre). Concepts such as giving and receiving, cultural diversity (métissage culturel), a universal civilization or Black African architecture appealed to us. And precisely on that day, that big sign brought up the issue of architecture. “Dakar,” Sédar would tell us, “will be a town of diversity, somewhere between the Cardo Decumanus and asymmetrical parallelism; between the reasonable use of asphalt and a tar flow leading to a garden of Palaver trees; between the feverish bitumen and the merry concrete, between the calm neon and the pristine glow of the moon.”

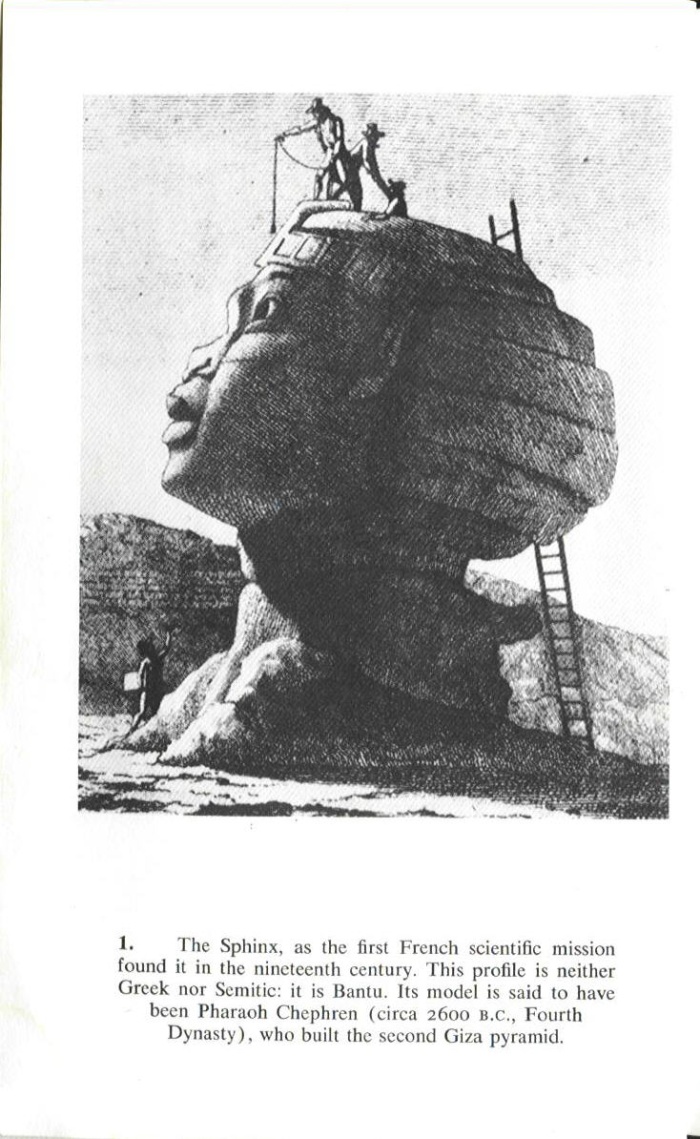

Cheikh Anta Diop, ilustracja z jego książki The African Origin of Civilisation. Myth or Reality (Nowy Jork 1974), źródło: archive.org

But alas, soon it turned out how wrong Mr. Senghor was. Yes, the Grand Master was wrong! When one promises something, they should keep their promise and he did not. He fell into a trap of false kindness and dubious loyalty. One should always be wary of faithful people, all the more so when they are unleashed. It is enough to whistle to a dog to call it back. It is a bit more complicated with a man: the more we whistle to him, the farther he moves away from us, taking with him half a century of patiently and judiciously built life, layer by layer, step by step, piece by piece. Just ask Mozart, let him tell you about Salieri! The history of humankind is full of these little stories of disloyalty, and coincidentally, inheritance always plays quite an important role in these stories. In this case and in this context, it was all about the legacy of Senghor.

His legacy is powerful and endowed with the virtue of ubiquity. It is everywhere, talking about everything and thinking about everything – in the broadest possible sense of this word. Culture, art, economics, education, health, science, nothing – absolutely nothing – is cast aside or left to its fate. The discourse is methodical and well-structured.

This way of thinking is two-faceted, like the head of an elephant with two tusks, symbolizing both wealth and weapons at the same time. The first one is immaterial and rooted in the collective memory. The second one is deeply implanted into a real and concrete place, connecting itself with the soil and coming up to the surface incarnated as a stone. And Senghor needed both the soil and the stone in order to be able to create a physical frame, to envelop his thinking. In the early 1960s, he chose three strategic locations: the first, suspended on a cliff near the Western Corniche road, stretching along the coast, was the National School of Fine Arts. The second, nestled in the heart of a modern building in Dakar’s Plateau district, was the National ‘Daniel Sorano’ Theater. And the third location was the Dynamic Museum (Musée Dynamique), scattered carelessly across the esplanade of a beautiful bay, one of many in Dakar. Let us take a brief moment to look at these three locations, which have connected us with Léopold Sédar Senghor by an unbreakable bond.

Lokalizacja pierwszej Ecole des Arts (obecnie całkowicie zniszczona). Zdjęcie: Nicolas Cissé

The National School of Fine Arts (L’École Nationale des Beaux Arts), called “the school of Dakar”

Initially, it was a place like any other, with no personality, just a former military base which happened to be a suitable home for a school for the blind. At the end of the 1960s, it was transformed into the National Institute of Arts (French: INA – Institut National des Arts). No one before this extraordinary conversion had ever imagined that these former barracks could be transformed into one of the pillars of contemporary African artistic thought.

It all started with the desire to create a research workshop. Research is inevitably linked with inquiry, i.e. with an effort consisting in presenting doubt as an initial assumption, and then gradually verifying its validity by the means of acquired and tested knowledge. Senghor, quite rightly, knew it. He had already experienced that: the West denies our contribution to a well-thought out, organized and architectured development, one that is reflected in our modern world. In the eyes of Western civilization, history has no examples of our utility or intelligence, as has already been said, written or suggested by many, most recently by Nicolas Sarkozy. [2] The legacy of Senghor stands as the only counter-argument to this grotesque thesis. The problem is that Sarkozy not only brashly advances his theses as Goethe, Voltaire, Hegel and others had done before him, but what is more – he did so from the sanctuary of Senegalese knowledge – at Cheikh Anta Diop University – and in front of a group of distinguished heads of states and African intellectuals.

Therefore, let us frankly admit that, at the time, that Senghor, as a young president, had a lot of work ahead of him! He had to quickly build a new school of art writing (écriture plastique), a school of architecture, theater and dance schools. It almost seemed like a herculean task, but Léopold Senghor took up the challenge without hesitation. Very soon he needed a contractor who would take it upon himself to perform this work. Clearly, the president elect was a man with a lot of experience and worldly wisdom, an actor capable of both astounding people and establishing deeper ties with them. A man of great courage who “dared to be black” in the heart of the African forest. An indomitable man capable of confronting irrational thought; geometry without a matrix; the forgotten colour.

Senghor could finally prove to his friend, Pablo Picasso, that modern Senegalese art has a place in European museums alongside the works of Kandinsky, Braque, Miró and Chagall. Léopold expected that his painters might become “big-headed”, but found it justifiable.

As if by chance, such an indomitable man was found! He had white skin and his name was Pierre Lods. He had just made himself comfortable in the Congo with the so-called Poto-Poto school which can be translated as “putting one’s hand to the dough.” In Senegal, two of his colleagues were waiting for him: they gained their ‘paintbrush & spatula’ experience in metropolitan France and their names were Papa Ibra Tall and Iba Ndiaye. The three of them had to work together and sharpen their skills in order to quickly educate the first generation of painters capable of imparting graphic expression to the message of renewal that had been formulated by the head of state, and make them available to the president-poet.

Soon, they gain the favor of heaven and fate is drawn to their side. The first generation undoubtedly enjoys baraka, the benevolence of the gods. Young artists of multiple and diverse talents have come to the fore. Today, despite the passage of time, we can still appreciate their art. Our memories of them are still vivid in us and the names of artists such as Ibou Diouf, Pathé Diongue, Amadou Sow, Souley Keita, Mor Faye, Mbaye Diop, El Hadji Sy are still engraved in our memory.

Pierre Lods, as befits a good teacher, knew how to reach out to his pupils. He allowed them free rein over their creative freedom. His teaching was based on the fundamentals of Black African aesthetics, such as sacred ritual masks or shapes and colors found in busy areas of everyday life, i.e. markets or places of celebration, in which the refined posture and the gait of our women lends ‘elegance’ its raison d’être.

Those fabulous moments of total creative freedom have enabled some of these Senegalese art students to gain recognition abroad, while others have decided to use their talents in other areas. A few, however, chose to stay alongside Pierre and join forces to enrich and consolidate Senegalese art. President Senghor needed to show the entire world that Senegalese art does in fact exist and is doing well.

And so art has become the showcase of Senegal which can be seen, touched, and almost felt. Exhibitions of Senegalese art are organized in many countries. The year 1973 will go down in the history of art – a ground-breaking exhibition of Senegalese art, entitled Senegalese Art Today, was held at the Grand Palais in Paris. Its poster continues to inspire many artists to this day.

Senghor could finally prove to his friend, Pablo Picasso, that modern Senegalese art has a place in European museums alongside the works of Kandinsky, Braque, Miró and Chagall. Léopold expected that his painters might become “big-headed”, but found it justifiable. His négritude is no longer left to itself. Now, it is supported by the artistic practices of the following artists: Ibou Diouf, Pathé Diongue, Amadou Sow, Souley Keita, Mor Faye, Mbaye Diop and El Hadji Sy. The great poet was aware that he was holding a pen in his right hand, and a brush in his left. He cared about his artists. He listened to them, indulged and pampered them. What he needed was the rebelliousness of Mbaye Diop, the visionary imagination of Ibou Diouf or the inspired cheek of El Hadji Sy. Sédar enjoyed their company and whenever he could, he spent time with them. Let the economy wait! And let the politics wait too! A thread of mutual understanding was established between Sédar and his artists. The president listened not only to the painters. He also made an attempt to establish the first school of architecture. It would be housed at the art school, quickly gaining recognition thanks to two of its students, Habib Diène and Nicolas Cissé, who, in 1977, won an international architectural competition in Paris, organized by the governmental agency for cooperation AGECOP (the predecessor of the International Organization of La Francophonie) which was attended by all French-speaking countries. The painters are no longer alone. Theater is also thriving thanks to the World Festival of Black Arts (French: Festival Mondial des Arts Nègres). The outstanding Douta Seck and his Haitian friends Félix Morisseau Leroy, Lucien, and Jacqueline Lemoine teach the rules of diction and declamation, and instill a love of the stage in actors. But the boards are not reserved solely for actors; they are also the domain of dance. The dancers move to the music of new rhythm and use new gestures. Dance is given a new face, the face of Germaine Acogny. The arch of her back exalts her roots, while the bulge of her breasts celebrates her sincerity among the rhythm of tam-tam drums played by the incomparable Doudou N’Diaye Rose. Thus we reach the second of the locations mentioned in the introduction, namely theater.

The National ‘Daniel Sorano’ Theater or the Advent of the Sorano School

When did Senghor happen upon the idea of encouraging the entire world to discover the achievements and values of Black African culture, to commune with it and appreciate it?

Was it in the aftermath of the International Congress of Black Writers and Artists held in Paris at the Descartes Amphitheater of the Sorbonne? Or was it during those sleepless nights when Alioune Diop and Aimé Césaire discussed the fundamental values of négritude? Or was it perhaps under the influence of the euphoria caused by the newly-won independence and the intellectual achievements which have contributed to such a coveted sovereignty? It doesn’t matter! In any case, everyone knew that the young president had an ambitious dream: to organize a large-scale festival of art and culture of the Black African population on the African continent, specifically in Senegal. Finally, the capital, Dakar, was chosen. Léopold could count on the resources and support provided by the international community. When he took the initiative, black people from all over the world, especially from the African Diaspora (Haiti, the United States of America, Martinique, Brazil, Latin America), enthusiastically welcomed the idea; for the first time in their life, they would be able to set foot in the land of their ancestors. Thus Senghor had a chance to test Senegalese hospitality, known as teranga, which is the reflection of his own philosophy of giving and receiving.

“For the first time in history, a head of state takes in his mortal hands the fate of an entire continent...”

Numerous guests representing rich and varied traditions were expected. The question arose, “Where should the event take place?” One had to act quickly. Senghor chose the theater which had been named after the late Daniel Sorano, who had passed away not long before. The choice was not accidental because Sorano, a leading French actor of the Comédie-Française, was of Senegalese origin on his mother’s side, and his contribution to culture in its universal scope was undeniable. He is a figure of considerable stature, not unlike Senghor’s friends from the intellectual and artistic milieu: Picasso, Sartre, Pompidou, André Breton and Paul Eluard; all the Parisian intelligentsia of the post-war years in other words. The project was entrusted to Sonar Senghor’s, the President’s brother’s care. Sonar did not disappoint him. Together they set up a modern theater hall with excellent acoustics and contemporary decor. The work neared the end in 1966 when the theater, equal to l’Opéra Garnier in Paris, La Scala in Milan or La Fenice in Venice, was established. From the very beginning of the first World Festival of Black Arts, the audience filled the theater to capacity, and black virtuosos from around the world performed on stage: Duke Ellington and his orchestra, the chorister Soundioulou Cissokho with his partner, Mahaweli Kouyaté, a singer herself, gospel choirs from Louisiana and the ‘Ballets Africains’ ballet company, with the young Isseu Niang whose feet did not seem to touch the ground. The place opened up to the entire world. The trembling voice of André Malraux declared in his inaugural speech that the ephemeral can become one with the permanent. We have the pleasure to quote an excerpt from his speech: “For the first time in history, a head of state takes in his mortal hands the fate of an entire continent...”

Thus the National ‘Daniel Sorano’ Theater, which eventually became a social phenomenon, was born. The most prominent Senegalese artists performed on its stage for over twenty years. The ‘Sorano’ Theater became an incubator of excellence, a must-stop for any representative of the world of Senegalese art and culture who wanted to be famous in Senegal and abroad.

The ‘Sorano’ Theater is also an important place for the emancipation and empowerment of Senegalese women: Henriette Bathily, Annette Mbaye d’Erneville, Mariama Ba, Line Senghor, Jacqueline Scott Lemoine Younousse Seye, and Isseu Niang. Female writers, actresses, visual artists, and choreographers took their place in the pantheon of knowledge and joined in the struggle for women’s rights. They followed in the footsteps of the inspirational Maria Skłodowska, best known as Maria Curie, an outstanding representative of her gender who brought the fight for women’s rights to a higher level and laid the foundation of modern physics with her discoveries.

But the ‘Sorano’ Theater is also a place of marriage between theater and cinema, a place of fruitful cooperation between prominent representatives of the Senegalese theater and the stars of Senegalese cinema. Thus great directors such as Paulin Vieyra, Sembène Ousmane or Djibril Mambéty Diop worked within the theater’s walls with such talented actors as Douta Seck, Iba Guèye, Line Senghor, Bachir Touré or Doura Mané Ndiaye Doss.

On the stage of the ‘Sorano’ Theater, a separate school of Senegalese film and theater is being developed, built step by step by the artists listed above, as well as by representatives of the cultural life of the African Diaspora (Haiti and the Antilles) who, after Fesman (The World Festival of Black Arts), decided to settle down in Senegal. They include: Lucien and Jacqueline Lemoine, Gérard Chenet, Joseph Zobel, Jean Brière, Félix M. Leroy, and Jacques Césaire among others. By putting down roots in the country of teranga, they bring the culture of diversity to the top of cultural universality.

Hall w Teatrze Narodowym Daniela Sorano. Zdjecie: Nicolas Cisse

Hall w Teatrze Narodowym Daniela Sorano. Zdjecie: Nicolas Cisse

Wejście do Teatru Narodowego Daniela Sorano. Zdjęcie: Nicolas Cisse

Wejście do Teatru Narodowego Daniela Sorano. Zdjęcie: Nicolas Cisse

Wejście do Teatru Narodowego Daniela Sorano. Zdjęcie: Nicolas Cisse

The Dynamic Museum or the School of ‘Broken Wings’

How many African museums could host, back in 1977, an exhibition of Pablo Picasso’s works? The Western world has very few museums which could stand up to the challenge. In Africa, there is not a single one.

But no one could refuse Senghor, especially since this is also an opportunity to give back to Africa what had been borrowed from it, in order to transform its art and guide it towards modernity. The Museum in Dakar, where the Picasso exhibition was held, is strangely reminiscent of the Parthenon in Athens. Helped by the ethnologist Jean Gabius, Senghor establishes a museum emphasizing the affinities and connections between Black African culture and Hellenic civilization. Thus, the architecture of the Dynamic Museum is a black Parthenon facing the Atlantic Ocean.

Picasso, the Museum’s guest of honor, behaved during his visit to the museum in a sincere and earnest manner, similar to the other outstanding visiting artists (Manessier, Soulages, and Hundertwasser) who graced the exhibition with their presence. Thanks to the high walls and the ceiling, the paintings could be hung three times higher than usual. Details are no longer important: the paintings gain in scale and some even gain depth. Under the influence of Soulages’ paintings, Senegalese artists attempted to paint giant-sized paintings. Mbaye Diop became the forerunner of this trend. A high-ranking government official who visited one of the exhibitions exclaimed: “How small we feel in the face of these paintings, despite our stature…”

It was Senghor who shaped a new vision of politics subservient to art, and not vice versa. It’s the culture which has seized power; the economy and the judiciary are its allies. During the first eight years of its existence, the museum hosted prestigious exhibitions of Senegalese and foreign paintings. Art was in its element. The Museum was preparing to welcome a distinguished guest who had links with this land. It was Maurice Béjart, the son of Gaston Berger, born in Saint-Louis, Senegal, the son of a mixed-race father and a Senegalese mother. A modern dance choreographer, the founder of the prestigious ‘Mudra’ dance school, who had won recognition on other continents, and was ready now to conquer Africa. His project won Senghor’s support. Maurice Béjart created a dance troupe known as ‘Mudra Afrique’ in cooperation with Germaine Acogny. The troupe prospered until the President departed from office. Once he left, the lights went out, and the judiciary came to the fore. Again, culture broke its wings. The Museum’s doors close, leaving twenty years of toil for the future prosperity and vision of society behind them.

Muzeum Dynamiczne (od 1988 przekształcone w Pałac Sprawiedliwości). Zdjęcie: Nicolas Cisse

Muzeum Dynamiczne (od 1988 przekształcone w Pałac Sprawiedliwości). Zdjęcie: Nicolas Cisse

Muzeum Dynamiczne (od 1988 przekształcone w Pałac Sprawiedliwości). Zdjęcie: Nicolas Cisse

*

Yes, the Grand Master was wrong! When one promises something, they should keep their promise and he did not. He fell into a trap of false kindness and dubious loyalty.

Now what conclusions can we draw from this? The effects of the painstaking work of many outstanding individuals, inspired by the president-poet’s lofty ideals, are in danger; men destroy faster than they create. We can only hope that, in the face of adversity, the legacy of Léopold Sédar Senghor and the artists who shaped the identity of négritude under the conditions of a young Senegalese state will not be lost.

However, the fate of these three places, so important for the Senegalese cultural and artistic life, is not the only flaw in the educational structure of our culture.

There is a fundamental omission of a very important element in this set of dialectical exercises, namely the revolutionary thought of Professor Cheikh Anti Diop. In the early 1950s, the then young black scholar, as audacious as he was talented, stunned the world of social sciences and anthropology with his opinion. His point of view was met with scorn from the Western academic community (as well as with indifference from the African scholars, including a lack of interest even from his compatriot, Léopold Sédar Senghor). It should be mentioned that at the beginning of the second half of the twentieth century, various rebellious ideas undermined all scientific, historical and cultural achievements of the white establishment. Anta Diop’s sharp and clear conviction can be summarized as follows: African civilizations predate Western and Eastern civilizations. Cheikh A. Diop also pointed out that the Greco-Roman civilization, the “cradle” of our civilization, was nothing but the heir to the civilization of Ancient Egypt. So far nothing new, but matters became complicated when the Senegalese scholar went further, explaining that the civilization of Ancient Egypt derived from the civilization of Black Africa which had been formed in Upper Egypt, on the banks of the Nile, in the area of modern-day Sudan. Diop argued that the European (Greco-Roman) part of that civilization was much more recent, as it was formed in fact only after the cultures of Lower Egypt and the Mediterranean metat the time of the Ptolemaic dynasty. Thus far, the tug-of-war between the West and its colonies had been limited to the peoples’ struggle for self-determination. Thus, the confrontation took place either directly on the battlefield, or as part of a dialectical, economic, cultural or social dispute. In other words, two opposite arguments clashed: the argument of the dominant white master and the argument of the subordinate black slave. This task was all the easier as it was based on the white master’s opinion that Africa had never been part of history. However, Cheikh A. Diop belied these fallacious assumptions, by stating more clearly than any other leader of that time that Black Africa was the founder of the civilizations which created the modern world. The world we live in.

To sum up, C. A. Diop was ahead of his own society. He was also ahead of Western society. The research and writings of the great anthropologists of twentieth century ideas stop in the same place as Diop’s ideas: this authentic heritage which, after presenting a new horizon, opened the way for a fair interpretation of a vision of the history of mankind.

Translation from the French by Monika Fryszkowska

BIO

Nicolas Sawalo Cissé is a Senegalese architect, film director, designer and activist. Since 1994 he served as president of the Association of African Designers, representing all African countries. The association cooperated with the organization "Afrique en Créations"; In 2005 he presided over the association "Coalitions Nationales pour la diversité Culturelle", which brings together all participants of cultural life (theater, literature, theater, architecture, fine arts); He took part in the struggle for the legal acceptance of diversity in the francophone filmmaking; He was awarded the Order of Chevalier of Arts and Letters [Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres] of the French Republic; Member of the Council of the Republic of Senegal in 2007-2010; Architectural Adviser for the President of the Republic of Senegal in 2009-2011; He made the first African film devoted exclusively to the environment, Mbeubeuss, le Terreau de l'espoir.

*Cover photo: (c) Joanna Grabski.

1. In Senegal, one can often find emotional use of the names of the first president, Léopold Sédar Senghor. Senghor - usually deals with his overall political program, Sédar refers to the person-president, poet and friend of the artist (ed.).

2. The author refers to the first visit to Dakar of Nicolas Sarkozy after taking office (in July 2007), during which he greatly angered the public opinion by allusions to the colonial past and the underdevelopment of Africa. (Le discours de Dakar). (ed.).