Timur Nowikow, "The Happieness in the Gardens" (1993-1994), atłas, druk, 214x168cm, 218.5x170cm. Zdjęcie: Anna Marczenkowa. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki

Time is what a clock reads. But this linear observance of time, from one second to the other, was actually invented once, no matter how profoundly embedded in our consciousness it may now be. The observance of clock-time, unlike the cyclical time of religion and myth, was a consequence of the industrial revolution and became closely tied with the rise of disciplinary institutions: schools, hospitals, factories. It would have been impossible for us to live in capitalism without synchronized time for labor. And this “industrial time” has not only changed the world, but it has become in fact our world. Is time then only a measurement? Of course the physical reality of time as a phenomenon, rich with intervals and irregularities, is very distant from the 24/7 timetable of labor in late capitalism.

Living, as we are, in the seamless time zone of the Internet, an apparently silent and invisible place, we have often forgotten the heavy industrial reality behind our networked condition: countless processors, heaters, coolers, and hours of actual labor. Set across the Ural region, a former industrial powerhouse of the Soviet Union and now a rather neglected region attempting to reposition itself, the 4th Ural Industrial Biennial is a laboratory to understand the possibilities (from within our inescapable situation) to turn around the inconsistencies of human time, our vulnerabilities, into a mechanism of defense that will keep us remotely safe from our own world, from the predictability of industrial time and the condition of labor. Is it possible to decolonize time, to free it from the role of authority?

During the six-hour journey from Yekaterinburg to Tyumen, you could stare into nothing but a vast white tapestry – grain fields fallen into a winter sleep, punctuated by makeshift hotels for long-distance drivers, gas stations and thick, kilometers-long forests. As a sojourner, you seemed trapped on an infinite straight line going nowhere. Upon arrival at the far-flung but oil-rich province, the first Russian settlement in Siberia, to visit the inaugural exhibition at the Tyumen Museum (special project of the Ural biennial), the sense of dread about the ubiquitousness of industrial time would drag on: a nondescript city, without a particular style, sprawling skywards, and reproducing anew the capitalist template.

In that sense, the exhibition Work Never Stops curated by Svetlana Usoltseva, was such an apt meditation on the transition from labor to laboratory, which is the issue that lies at the heart of the three-part biennial. Taking as a starting point the colorful floral ornaments of the traditional Tyumen carpet, the title paraphrased Eliza Bennett’s celebrated video A Woman’s Work is Never Done (2012), on show in the exhibition, showcasing a woman embroidering onto the skin of her own hand, placing it in the regional context where women’s labor is assumed to be unimportant, in contrast with the industrial labor of men. But the long and time-consuming act of weaving, without definite beginning or end, belongs nonetheless in the chain of industrial production and is a very acute metaphor for the architecture of power.

It is a structure so dense that while visible from above, it is impossible to reduce it to its basic units. There had to be the obvious works in the exhibition about weaving, such as local artist Alisa Gorenina’s textile installations or the well-known carpet deconstructions by Azeri artists Faig Ahmed, addressing the challenge to tradition. Yet, rapidly enough, the exhibition moves from act to question with the melancholic textile banners, Happiness in the Gardens (1993–1994) of the late Timur Novikov, one of the most influential figures in Russian non-conformism, who sought a place for aesthetic experience in a technological society yet to come (by the end of the Soviet era, it was believed that it would come much faster).

And in-between there is a lot of other work that references traditional weaving, from the photographs of Roman Mokrov to the activist art of Nadenka Creative Association, or the appliqué bear series by Olga Subbotina and Mikhail Pavlukevich. But it is in the last section, Time / Process that the reflection comes to fruition: the mesmerizing text time-frames of Irina Korina (five minutes, a minute, a couple of years) from the Temporary Phenomena series reveal the actual “quantity” of time to be such a strange promise. They are complemented by videos by Vladimir Logutov, Svetlana Spirina, and Provmyza, which address infinity in terms of its tortuous interminability. When will time end at last? Is there a way out?

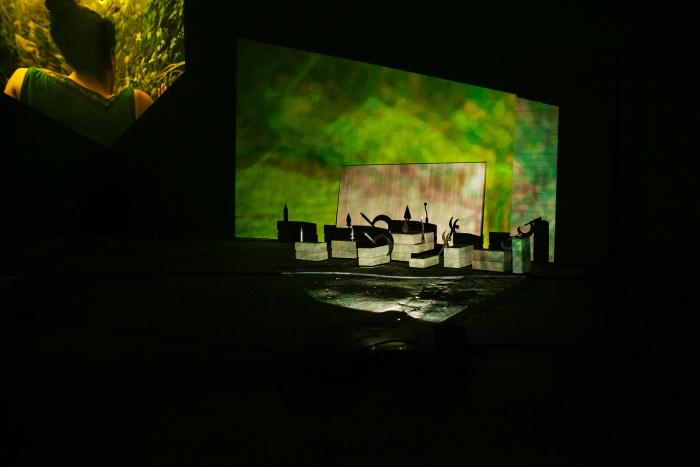

Irina Korina, z serii "Zajwiska tymczasowe" (2016). Instalacja, papier, akryl, pleksiglas, metal. Zdjęcie: Anna Marczenkowa. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki

The central piece of the exhibition, however, is the performance/installation of Yekaterinburg’s collective Where Dogs Run, Knitting and Crocheting a Mandelbrot Set (2006–present), in which a guest performer is knitting crochet patterns for several hours; a scheme generated by the two parameters that make up the Mandelbrot set, the first fractals in history. Through intensive labor, the two-dimensional set is transformed into a three-dimensional volume. How does something appear from nothing? The delicate performance dissolves the boundaries between labor and creative process, relying on a rather simple mathematical formula, endowing complexity with a physical body. A transubstantiation between a creative act and objective authorless knowledge.

Where Dogs Run, Dzierganie i szydełkowanie zbioru Mandelbrota (2006-obecnie), performans, instalacja. Zdjęcie: Daniil Savinykh. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty

The poetry of time as a medium and material continues and expands greatly at the main project of the biennial in Yekaterinburg, New Literacy, curated by João Ribas. The ambitious exhibition frames the question of capitalist temporality and the mechanisms of its interruption: prisoners as we are of uninterrupted time (the sleeplessness of the marketplace), are we perhaps in the middle of a revolution comparable in scale to the previous industrial revolutions, but based entirely on information? The question of information is of course tricky, because information is not knowledge or history. How do we move on towards infinity without a history to show us the way? Tackling the disenchantment with the imaginary of technologyin the post-Soviet world is an act of reimagining oneself for the future.

Reading the exhibition in reverse, from Tyumen to Yekaterinburg, the factories have already closed (the biennial site was in fact an industrial site, about to be gentrified), and the current “network structure” presents us with a rather formless and incomprehensible world. The text installation of Azeri-French artist Babi Badalov opens up our senses to the interface we are about to enter. RainCarNation (2017) is a lexicon of late capitalism that playfully oscillates between slogan, poetry, ideology and everyday language: “Manipulation, womanipulation,” “Formal East, Formal Easm,” “Political Prisoners, Poetical Prisoners,” “Com Moonism.” What does it mean when we say something? Utterances become devoid of meaning in the massive overload of our limited senses before the power of the Internet.

Babi Badalov, “RainCarNation” (2017), technika mieszana, instalacja. Zdjęcie: 4th Ural Industrial Biennal, dzięki uprzejmości organizatorów

Yet, technology is both dystopian and utopian. Urban Fauna Lab’s Sauna (2017) is a hothouse heated by the cooling of processors that mine crypto-currency. Although the currency is analogous to real money, the most abstract symbol of capitalism, crypto-currency is in fact digital information, one of the core materials of contemporary life. Hereby, it acquires a physical dimension that can also interfere with biological and ecological processes; from processor to natural process. Where Dogs Run, on the other hand, are present in Yekaterinburg as well, with Evaporation of the Constitution of the Russian Federation (2017), a playful installation in which the text of the Russian constitution is translated into Morse code and transmitted in the form of steam through drops of water on hot irons. Perhaps data and information are not completely neutral anymore.

Where Dogs Run, “Evaporation of the Constitution of the Russian Federation” (2017), instalacja. Zdjęcie: Zoom Zoom Family. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty

Amidst this flow of failed utopias and nascent heterotopias, the forms of knowledge that this new “literacy” seeks are not merely historiographical corrections or sociological diagnoses, but a calm and sober question: how do we tackle historical change if we are the subjects thereof. In And yet my mask is powerful (2016), an installation by Palestinian artists Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme, the question surfaces of how to reconstitute living matter (people, places, things) from ruins? Young Palestinians take trips to destroyed villages in order to rethink what it would be like to reconstruct something once the referents who can identify its characteristics have gone missing. Against a perennial cycle of violence and destruction that has metastasized with the fabric of the real, in the context of Yekaterinburg, the mask is a metaphor for the present; a way to interrupt the condition of hopelessness.

Basel Abbas & Ruanne Abou-Rahme, “And Yet My Mask is Powerful (część 1)” (2016), wideo 8'44. Zdjęcie: Anna Marczenkowa. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki

Yet there would be no notion of the faraway, of the gap between history and technology, and the distance between our world and ourselves, if we did not have points of comparison. In Impossibility of One Page Being Like the Other (2014), Arab artists Ala Younis and Oraib Toukan use discarded footage from now defunct Soviet cultural centers in Amman as a commentary on the oversupply of images from the past, which is a very present trope in present-day Russia. Young Russian artists are also taking part in the historical reframing: the paintings of Pavel Odetnov depict industrial ruins from the city of Dzerzhinsk, the capital of the Soviet chemical industry, in which his family has worked for generations, and Alexei Shchigalev’s drawings feature industrial machinery from the Chusovskoy Metallurgical Plant.

Aleksiej Szczygalew, “Surface Tension (Napięcie powierzchniowe)” (2015), instalacja. Zdjęcie: Zoom Zoom Family. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty

A project at the heart of the Ural biennale that stands out in highlighting the complex relationship between history, technology, politics and the built environment is: Alexandra Paperno’s On the Sleeping Arrangements in the Sixth Five-Year Plan (2017), based on her eponymous 2012 paintings. It refers to the 1955 resolution of the Communist Party, “On Eliminating Excess in Design and Construction,” which gave rise to a mass construction program that would make housing affordable and available within a short time frame. How much space is necessary to undress and lie down in bed? Housing size was regulated down to the centimeter. The installation cleverly reproduces the rooms based on the plan. At the entrance, there is a concrete monument with the engraving “Non Finito,” which bears witness to the extraordinary scale of this program. Modernity in ruins as commentary rather than imaginary.

Aleksandra Paperno, “On the Sleeping Arrangements in the Sixth Five-Year Plan (O układach sypialnych w Szóstej Pięciolatce)” (2017), instalacja, technika mieszana. Zdjęcie: Anastazja Sobolewa. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki

Aleksandra Paperno, “On the Sleeping Arrangements in the Sixth Five-Year Plan (O układach sypialnych w Szóstej Pięciolatce)” (2017), instalacja, technika mieszana. Zdjęcie: Anastazja Sobolewa. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki

Aleksandra Paperno, “On the Sleeping Arrangements in the Sixth Five-Year Plan (O układach sypialnych w Szóstej Pięciolatce)” (2017), instalacja, technika mieszana. Zdjęcie: Anastazja Sobolewa. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki

Sites of nuclear disaster (or oblivion) from Soviet history are reimagined by Tasya Korotkova in tempera on gesso on wooden panels, which imitate historical narrative paintings from the 16–17th century, thus producing the impression of a long-foregone past, pointing to the condition of modernity as an archaeological artifact, subject to decay. Grand narratives are hereby reduced to souvenirs of the past. These imaginaries of remote futures that run deep in Russian cultural and political life, often with the connotation of catastrophe, are placed side by side in the exhibition together with the anxieties of Western contemporary art in its obsession to break out of our current future-present into a far less self-contained notion of subjectivity that can accommodate plurality not only as divergence of opinion, but as a worldview; political, scientific, economic. The belief that new systems might yet become possible.

Aleksandra Paperno, “On the Sleeping Arrangements in the Sixth Five-Year Plan (O układach sypialnych w Szóstej Pięciolatce)” (2017), instalacja, technika mieszana. Zdjęcie: Anastazja Sobolewa. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki

Aleksandra Paperno, “On the Sleeping Arrangements in the Sixth Five-Year Plan (O układach sypialnych w Szóstej Pięciolatce)” (2017), instalacja, technika mieszana. Zdjęcie: Anastazja Sobolewa. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki

Aleksandra Paperno, “On the Sleeping Arrangements in the Sixth Five-Year Plan (O układach sypialnych w Szóstej Pięciolatce)” (2017), instalacja, technika mieszana. Zdjęcie: Anastazja Sobolewa. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki

With long dark corridors of videos and installations across several floors, sound and images bombarding you from everywhere, New Literacy is the closest you could get in a physical space to a thread on Reddit or Twitter; the intoxicating angst of freedom, the vertigo of information surplus. How can a distinction be made between man and machine given today’s technology, asks Harun Farocki from one of the video booths in his iconic Eye/Machine II (2002), collecting data from machines and warfare technology, making us wonder what it is that we see, what is the gaze from nowhere looking at, and pondering on the obsolescence of our own eyes: most of the images that we see, that we carry in our pockets, are not man-made. Perhaps we are learning to look at our own world through the eyes of satellites and surveillance devices.

Turning to the same technology in order to create the most heart-wrenching piece in the exhibition, tucked in a distant corner is Forensic Architecture’s The Left-to-Die Boat (2014), which relies on forensic oceanography to reconstruct how different state actors operating in the Mediterranean deliberately refused to aid a boat from which sixty-three migrants drowned after being adrift for fourteen days on the most surveilled waters on Earth. The straightforward storytelling, accompanied by overwhelming amounts of data, make the viewer feel both hypnotized and helpless. Sometimes you wonder whether this is a video game, followed by the shocking realization that real-time data actually exists. Is it through moments like this that the exhibition opens up an abyss before you, offering no glimpse of salvation or a navigation map. It is almost a cosmic viewpoint: you and I are alone down here.

Forensic Architecture, “The Left-to-Die Boat (Łódź pozostawiona na śmierć)” (2014), wideo, 17'59”. Zdjęcie: Zoom Zoom Family. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty

But of course, thinking about these new forms of knowledge and the possibilities of revolution today (it is noteworthy and paradigmatic of our situation today, for example how Russian parliament is currently discussing a proposed bill that would forbid private military contractors from the country to participate in uprisings and revolutions anywhere) is not a solipsistic conversation between the ego and myself, but one about our own agency for politics (what was once called the social question), and therefore the relational ability to bear our own condition. Faced with an unpredictable past, ahead of us, the reality of labor time is not a sociological construction, but another phase in the omnivorous and rather unquenchable thirst of colonial space.

The transformations that the world has undergone in the industrial era are in fact irreversible: from the abandoned industrial sites throughout Russia and the former Soviet Union (here we are not talking about nuclear waste even, but the large-scale deindustrialization and impoverishment of vast swathes of territory) to the agro-environmental disasters throughout the former colonial domains: Africa, Latin America, Southeast Asia. The irreversibility of these processes is not necessarily the end result of capitalism, but in fact capitalism itself. And the fact that the bio-consumption of the earth continued at the same speed under the socialist program can only indicate the degree to which the temporality of industrialization is supra-political; it aims to be contained within the human condition.

Colonial space and industrial time are not one and the same; the former precedes the latter. At first, the living ecosystem that contains our living places is spatialized (in mathematical terms, statistics and maps, the entity is defined – there is no longer a promised land), atomized into an abstract whole and along the way, devoid of its primary content (from now on, there will be only secondary content, “renter,” “leaser,” “inhabitant”). Once the territory has been cleared out, clock-time can enter the picture. In this spatial-temporal continuum, reproducing the template of capitalism, there is no end to resources. In theory, the creation of value will lead to the multiplication of value. Yet in reality, like the Biblical locust, once resources have been depleted in one site, new colonies ought to be established.

Desertification and erosion, these are not only notions of the natural world – we have not lived there for a long time; we are only reminded of it when the processes set in motion by industrial time clash with its finitude, and send us notifications in the form of drought, famine, natural disaster. There is also a process of desertification inside of our cities, and therefore in the social fabric. Is the urban desertification fast-tracked by industrial time, potentially deadly? We know that the answer is yes, but because industrialization is a form of the past (earlier glories, dominion over nature, empire) rather than the future, we seem to be adamant in our conviction that it can be neither changed nor stopped. The economy of environmental engineering and post-apocalyptic (upscale) urbanism is very much alive.

But today, the logic of industrialization and the logic of technology have parted ways. While the imaginary of technology is still almost naively ahistorical, the transition from the factory to the digital space (where there is real value) has liberated technology from vertical hierarchies. Nevertheless, as the reconfiguration of capitalism takes place, it begins to attempt to colonize time again. This time of the postmoderns, on the other hand, is a seamless and almost unembodied whole, a kind of “nunc stans,” without beginning or end, so vast that it encompasses almost infinity but so fragmented that it is ungovernable. Is it perhaps what Ribas meant to grasp within the exhibition? Immersed in so many images as we might now be, are we perhaps losing the understanding of the grammar that articulates power?

As a whole, the Ural biennial never turns to despair and remains rather firmly anchored in the real as the only currency to buy our way out of this current Machiavellian moment. At times claustrophobic and interminable, the exhibition is often a test in visual and emotional saturation, combined with the paralyzing effect of the geographical distances covered and the urgency of the questions proposed, adding a layer of unambiguous political commentary on Russia. The recovery of the public domain from a neoliberal strangling seems to be at stake here in the active transition from labor to creation that we witnessed in works such as the performance by Where Dogs Run. As Hungarian philosopher Agnes Heller put it, “Curious as we are, we do not know when, how and where we are to arrive, or whether we will arrive at all. What we know for sure, is that the next installment of the story will be written by us.”1

BIO

Arie Amaya-Akkermans is a writer based in Istanbul and Moscow. His work on contemporary art appears regularly in Hyperallergic and has been published previously in Canvas, RES Art World, Art Asia Pacific, San Francisco Arts Quarterly. Moderator in the programme of talks at Art Basel in Miami Beach and Basel (2015–2016), expert fellow at IASPIS (Stockholm), guest speaker at the Royal Institute of Art (Stockholm). Amaya-Akkermans is the author of several publications devoted to artists, co-author of the monograph Michel Basbous about the eponymous Lebanese sculptor (2014), guest editor of ArteEast quarterly, and a speaker at the conference Modern Oriental Art: Key Processes, Methods of Study, Problems of Museification held at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art in 2017. His most recent publications include the catalogue Massoud Arabshahi: Early Works from the Azari Collection, alongside Mahnaz Fancy (Lawrie Shabibi Gallery, Dubai) and Pictures of Nothing devoted to the eponymous group exhibition (curated by him at PG Art Gallery, Istanbul), alongside Bilge Friedlaender, Jeniffer Whittier Mackenzie, and Keyla Cavdar.

* Cover photo: Alexei Shchigalev, “Surface Tension” (2015), installation. Photo: Zoom Zoom Family. Courtesy of the ZZF

[1] Heller, Agnes. “Can Modernity Survive?”, pp 173, University of California Press, 1990