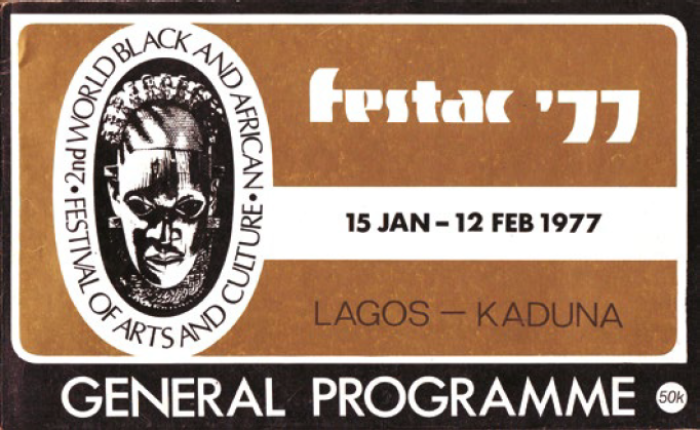

The Nigerian National Theater located in Igamu, Lagos state, was constructed as the great architectural showpiece of FESTAC '77. Festac '77 is the acronym for the Second World Black Festival of Art and Culture, an event that Nigeria hosted in 1977 as a sequel to the first world black art festival hosted by Senegal in 19661. Constructed by a Hungarian firm and shaped as a crab, the National Theater has remained perhaps the most lasting iconic symbol of the historic Festac event. But apart from its importance as a national/pan-African monument to the triumph of the spirit of cultural-nationalism and Afrophilia that had seized hold of post-Independence Africa, the National Theater is perhaps better known for its unenviable fate at the hands of the successive governments of Nigeria. Left for long stretches of time in various states of neglect, disrepair or near-total ruin, it's successive managements notoriously corruption-ridden and its cultural role and impact long faded from public memory, the National Theater has come to symbolize all that is wrong, ill-formed and sick not just in the arts and culture sector but also concerning the very structure, architecture and functionality of nationhood in Nigeria. Today, the ill-fated condition and dysfunctionality of that modern monument to national and pan-African artistic consciousness appears to be at its nadir. As recently revealed by a top government official before the National Assembly, the latest about the National edifice is that the Federal government is considering selling it to raise money to fund the 2018 national budget 2. In this piece, I want to read the many vicissitudes of the National Theater as mostly symptomatic, first of modern art’s neurotic struggles with the unmodern reality in Nigeria; secondly, as the aporia of nationhood and of modernity in Nigeria. Some of the questions that will guide my reflections include: Given the peculiar architecture and structure of post-colonial Nigeria, what are the aesthetic possibilities available here? Can a monstrous mechanical aggregation of largely untransformed tribes make a modern nation? What is the fate of modernity and national art in a setting like ours? Under what contrary conditions can a modern national art thrive? In answer to these and other questions, I will examine how the misfortunes of the National Theater as well as of national art and culture mirror the inner dysfunctional hybridities of the post-colonial mind of the Nigerian elite. I will start by returning to the peculiar cultural-nationalist/anti-colonial ferment that birthed Festac, the National Theater and what can be called, “the Festac spirit” of modern art and politics in Nigeria.

Front teatru narodowego i flagi krajów uczestniączących w Festacu.

Festac and the birth of Afrophilia in art and culture

As stated earlier, the National Theater was the by-product of Festac’s massive revival of the ancient past, the traditional arts and cultures of Africa and the Black world. Monumental in its architectural design and ambitious in the pan-African reach of its symbolic efficacy, the edifice was conceived mostly to embody, celebrate and showcase the emergence and exemplary flourishing of national arts and culture in what was supposed to be a modernizing Nigeria awash with oil wealth and the swollen will to remain the giant of Africa. Though the architecture of the theater was wholly modern in its conception and execution, the spirit that engendered and drove Festac was emphatically not; Festac was the apotheosis of traditionalism. The term cultural-nationalism can be said to capture the conscious anti-modernity traditionalism that gave birth to Festac and its aftermath in Nigeria and the rest of Africa. Cultural-nationalism encompasses the whole gamut of ideas, race worries, nativist nostalgia and anti-colonial anxieties which, drawing inspiration from the Negro Renaissance movement in America and Negritude made in France, had seized hold of the acculturated elite of Africa and the Black world and caused them instrumentalize native traditions, cultures and arts as weapons of self-affirmation and self-assertion as well as anti-colonial emancipation. Festac was all those grand theories of Black/African specific racial/cultural identity removed from books, embodied in performances, taken to the market place and performed live on the world stage. A grand celebration of the uniqueness and wonders of the negro-African heritage all over the world, it was also the grand ritual act of the final redemption of Africa from the pre-civilizational none-entity where Europe since Hegel had dumped the Dark continent. For two months between January and February 1977, thousands of artists, musicians, performers, etc. from all over the Africa and the Black Diaspora gathered in Lagos to celebrate and showcase the infinite riches of Africanness/Blackness.

However, the trouble with Festac was that most of the cultures, traditions and arts showcased as quintessentially African belonged exclusively to the archaic pre-colonial ancestral world. Cultural/artistic Africanism was framed mostly as a hypertrophy of nativist nostalgia; the African identity celebrated was captured as suspended and fixed in a pre-colonial ancestral past. Ancient traditions extracted from the living forces of colonial and postcolonial histories were presented as the embodiments of an essential and unchanging Africanness. This obsession with an image of Africa subtracted from the historical dynamics of the postcolonial becoming of the African world defined the essential and unyielding Afrophilia of Festac. Afrophilia, is about the obsessive love for Africa, the compulsion to assert and defend our Africanness, to project in all we do and say, the African way of life, or the African identity etc. This Afrophiliac impulse was the driving force of Festac, the spirit behind the nativist narcissism of its many shows. But we must also note that that which triggered and fueled Festac Afrophilia was none other than the elites’ anti-colonial paranoia. Colonialism was accused of having not just dis-membered Africa but more importantly, of having badly damaged the African soul. Festac was a soul-restoring ritual response to colonialism’s cultural and spiritual vandalism in Africa. Given its symbolic healing and restoration value, the Festac/ Afrophiliac spirit was to take over and rule art and culture in Nigeria by deflecting all creative energies of the nation from the modernizing historicity of our postcolonial condition to a near-exclusive preoccupation with the revival and replication of the antiquated forms of the ancestral world. Art and culture rather than learning from the past and overcoming the counter-evolutionary blockages of the old world, stagnated for several decades at the reproducing replicating often under new guises, the mostly magico-mythic lifeforms and other cultic symbols and images of the archaic world. Art and culture in Nigeria post-Festac was essentially centered around reproducing tribal masks, juju shrines, traditional dance, tribal stage epics, ancient animist cults, and tribal folktales. Art and culture became not explorations of the newer creative possibilities of life in the postcolonial theater of world history but what were done to cage the imagination and shield ancient tribal cultures and traditions from the transformational impact of modernity. In other words, art and culture became knowingly or unknowingly, instruments for the continual defeat of modernity and progress in Nigeria. Having infected the national spirit, inoculating it with the virulent virus of neo-nativism, the Festac impulse was to affect most other aspects of national life including politics and development. Afrophilia glamorized and diffused by Festac had already infused the elite with a militant nativist self-conception along with a victimly anti-colonial world interpretation.

Enveloped in these twin paranoid shells, the Post-Festac Nigerian elite along with other African elite was to embark on a specific African path to development [The Lagos Plan 1980]3 rooted in the revival of African traditions and values and fuelled by an essentially anti-west interpretation of our location in post-imperial modernity.

What is this Festac spirit that birthed both the exquisite modernity of National Theater and the anti-modernity nativist spirit that gnawed at the very roots of the edifice and ensured its non-functionality under our climes? The Festac spirit is essentially the spirit of Afrophilia. It is a deep emotional yearning for the lost ancestral warmth of the tribal hearth; it is nostalgia for life in the quasi-state of nature, of fusion between man and nature. It is the longing for what Senghor had poetically sung as the kingdom of childhood, the animist state of participatory consciousness from which colonialism had so wickedly snatched the African. The Festac spirit in the arts consists of reliving the diremption or alienation from Africa’s ancient wholeness as the primal trauma of the African condition. Literature but most especially the visual and performance arts including dance, theater, film etc. exist and are continually mobilized to heal the loss of our Negritude or original ontological wholeness, and also to work towards the actual embodied or symbolic retrieval of the lost wholeness. Post-Festac art and culture have remained mostly instruments of nativist nostalgia as well as vehicles of unfinished anti-colonial resentment. In other words, the combination of nativist narcissism and anti-colonial paranoia drives the essential Afrophilia of post-Festac art and culture in Nigeria. A most instructive case of how the Festac spirit of unremitting cultural nativism/anti-colonial paranoia in Nigeria has interfered with a normal aesthetic evolution in Nigeria is the advent and proliferation of the Nigerian version of what has come to be known as African modernism.

Festac spirit and Nigerian Modernism

One version of the story of African modernism in Nigeria centers around the pioneering activities of the German couple Uli and Georgina Beier, and Susan Wenger with a few other Europeans who, in the 50s and 60s of the last century organized art workshops in the Nigerian towns of Osogbo, Ibadan, etc. The workshops attracted mostly jobless village drifters who wandered there merely out of sheer curiosity to see what a tiny band of white people were doing in their remote native towns. Without the least previous exposure to or training in art, these curious villagers were to form the nucleus of what came to be known as Nigerian modernism. The term modernism was applied here not only in direct reference to the modernist art revolution of the 20th century but mostly because of what can be termed the “Picasso moment” in African art. The “Picasso moment” refers to what ensured after Picasso saw an African mask for the first time. Cubism was allegedly born when Picasso, transfixed by the sight of a Congolese mask, went home to create Les Demoiselles d’Avignon as the inaugural work of a new art movement, namely Cubism. That incident was interpreted by Africa’s elite as Africa’s massive energizing contribution to the revival of Europe’s near-dead artistic imagination. Secondly, it was seen as Picasso’s or Europe’s aesthetic-cultural endorsement of African cultural primitivism and by extension, as support for anti-colonial cultural nationalism including Negritude’s call for a massive return to our authentic African source. The Europeans who organized art workshops in Nigeria [ and in a few other African countries] came mostly as Picassoist primitivists coming to teach Africans how to turn the untapped artistic treasures of their traditional or primitive cultures into modernist artworks. And so, without being exposed to any formal art education, the students were simply given paint, brush, knives, pencils and asked to start painting, drawing, or sculpting whatever came into their heads. There were no directives, no limits, no conventions but just a kind of surrealistic automatic painting, drawing or sculpting. Of course, they were expected to draw their subjects, themes and inspiration from the riches of their magic-filled, heavily enchanted local environment. At the end of the exercise, all manner of quaint images, monstrous drawings and sculptures all of them inspired by and depicting local pagan deities, shrines and masks were then given titles by their surrealistic [non]teachers.4

And so it was that Nigerian modernism was born out of the arbitrary juxtaposition of African native contents with the surrealistic, abstract or de-humanizing styles of European modernism. Under the cultural nationalist spirit of Festac, Nigerian modernism was celebrated as Africa’s original contribution to the most advanced artistic culture of the 20th century. African modernist artworks became tools in the service of the much-coveted cultural recognition by the West. And so quaint pieces without beauty or meaning, bearing no resemblance to what had hitherto been known as art, were produced en masse as new artists strained to concoct strange new works that spoke only to western audiences but were virtually unconnected with the rest of culture in Africa. However, blinded by the Afrophiliac/cultural nationalist fires lit by Festac, no one questioned what the new art meant; whether it meant anything at all; whether Nigerian modernism amounted to a valuable artistic evolution or it was merely a counter-evolutionary cultural freak and an empty copy-cat modernism that merely allowed Africa to dodge the hard, evolutionary task of rational, orderly transition to modernity in art, culture, politics and society. The leap into artistic modernism at a time when Africa was not even near the threshold of cultural, social and material modernity has remained a telling symptom of the many undone and skipped works of preparing Africa for transition to modernity. In Nigeria the proliferation of modernist works reinforced by the Festac spirit of Afrophilia became a pointer to the what we chose to do with modernity, how we operate all modernity projects especially nation, democracy and culture: namely by super-imposing upon an unchanged and untamed native life-world, borrowed, ill-adapted thoughts, vocabularies, practices and institutions that are both evolutionarily different from and incompatible with it. I will like to illustrate the last point by describing how the post-Festac nation works to make it difficult for modernity, culturally significant art, rational order, moral and material progress to thrive in Nigeria.

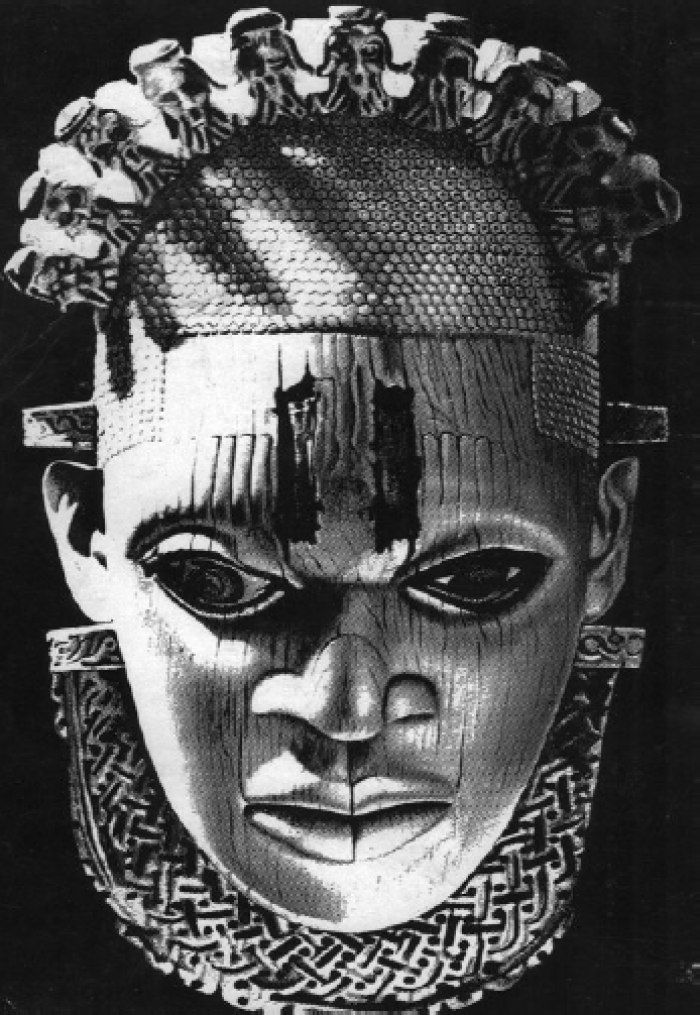

Benińska maska z bronzu, symbol Festacu.

Nation, modernity and politics in post-Festac Nigeria

Just like African modernism in Nigeria is a puzzling amalgam of incongruities and falsehoods, the Nigerian nation, a multi-tribal patch work, is a dinosaur-like assemblage of incompatible parts and unsynchronizable elements. Having inherited a vast colonial territory from Britain, the “nationalists” proceeded to label it a nation-state but without the least change or modification in structure, composition, form or usage. In other words, the label “nation” was merely pasted upon a mechanical aggregation of tribes and religions like a bandage upon a gaping sore. Without any cultural conversion, worldview transformation and without any change in tribal habits and mentalities, Nigeria, like most other African nations, entered modernity as a nation-state. To justify and legitimate this mode of entry into the modern world, the ideology of Africannness or Africanism was invented to spell out a specific African path to development, African socialism etc. Festac was staged to provide cultural backing to and confirmation of this specific African way, and right of way, in modernity. But the African modernity that ensued particularly in Nigeria was an affront to and a travesty of the rationality and order that underlies and drives modernity elsewhere and ensures in those places orderly progress, economic development and human well-being. The post-Festac African modernity in Nigeria was modernity without development, order, peace and humaneness. The nation works by trying to integrate the many tribal traditions including juju into the institutions and practices of modernity such as the state, politics etc. The result is a hybridised monster which, as Chabal and Dolez had observed, functions only when put in the irrational mode of disorder, juju, witchcraft and corruption5.

The state operates by patent falsehoods which often include turning the incapacitating aporias of a multi-tribal nation-state into new voluntaristic virtues of the African path. Thus, the incapacity to forge an organic modern nation out of disparate tribes, tongues and religions becomes “unity in diversity” or the cry of desperation “the unity of Nigeria is not negotiable.” The incapacity to develop and modernize becomes the pursuit of an African path to development; the inability to leverage and fructify colonial cultural contact and knowledge becomes the imperative and desire to decolonize our minds; the inability to keep up with the rigors and discipline of western learning and science becomes the decolonization of knowledge and the Africanization of the curriculum.

As the nation was simply built over unconverted tribalism and untransformed disparate traditions, national culture becomes the odd assemblage of many tribalisms rather than an evolutionary transcending of the tribal consciousness. The trouble is, the nation as an idea and practice, is a quintessentially modernity project which presupposes that the citizen is no longer a tribesman, i.e., he has successfully evolved out of magic/tribal consciousness into the more universal rational-scientific consciousness that undergirds modernity. In Nigeria as in most other African countries, the transitional phase from tribe to nation, from magic to science was notoriously skipped. The Fanonian anti-colonial passion that animated African nationalism coupled with the Afrophiliac hysteria whipped up by cultural-nationalist propaganda, did not allow for any rational, long and orderly transitional phase during which the African would have been gradually weaned from millennial tribal culture and equipped mentally and socially to transit to the completely new and different order that was modernity. For the Fanonian nationalists, decolonization was just taking over with immediate effect, the white man’s seat. Hence the near-tragic aporia of modernity and nation particularly here in Nigeria. In Nigeria, national consciousness is a kind of neurosis in the sense that it is a survival formula which allows citizens still fully rooted in their tribal identities, and perceiving the nation as an abstract imposition, to relate to other tribesmen in ways best suited to his personal/ethnic interests. The multiple identity syndrome here, i.e., a tribesman wearing a national mask and professing one of the two foreign religions, translates into an irresistible urge to subvert the common good, to steal and embezzle public funds without any bad conscience. The quasi normalization of corruption in Nigeria can be traced to the dominant power of the tribal impulse which unconsciously reasons that by stealing from the state, the agent is only securing for himself and his tribe resources that would otherwise have fallen into the hands of someone from a rival tribe.

Art and cultural institutions in a dinosaur-nation

What is the fate of art, culture and cultural institutions in a multi-tribal dinosaur-nation like Nigeria? How have the monstrous structural defects of nationhood in Nigeria affected the arts, cultural institutions and policy? What is most obvious is that given the massive incongruities that compose Nigeria’s postcolonial culture, a truly national art and culture appear mostly as the products of the uncannily monstrous for they bear the imprints of neurotic struggles with multiple and mutually incompatible layers of reality. National art, as opposed to art rooted in and driven by ethnic imagination, often appears either as an impossible amalgam or the forced product of aesthetic-political bullying. The nation appears to repel any unforced national aesthetic harmonies or spontaneous outburst of natural beauties. A graphic illustration of this is provided by the generic musical piece that prefaces prime time national news on the Nigerian government television station, called the NTA (Nigerian Television Authority). In that important piece of national art, motifs from the three dominant tribes, namely, Hausa, Yoruba and Igbo, were selected and brought together to form one synthetic national musical piece. Sounds from traditional Hausa horns were juxtaposed with Yoruba tribal ritual drums and the two sounds interspersed with Igbo xylophone tribal music. With a lot of aesthetic-political engineering, attempts were made to fuse together into one coherent national music, these separate primitive sounds coming from divergent tribes. The strange thing is that no matter the amount of editing and political engineering work expended, these divergent, wild primitive sounds will not cohere, will not fuse together and form one harmonious whole; worse still no such fusion seems possible at all. What results is a cacophony of wild primitive tribal sounds seemingly at war with each other but forcibly juxtaposed without the vaguest intimation of any future aesthetic harmony. The NTA network generic music is perhaps one of the earliest and most ambitious attempts to forge a national art work out of the plurality of tribes and cultures that make up modern Nigeria, but that effort has fallen abysmally flat. What that monstrous abortion of national musical aesthetics shows can be summarized as follows: [1] it is easier to exist as the giant of Africa defying all political evolutionary gravity than to be capable of giving birth to beauty, order and harmony. [2] That beauty as art, political order or moral progress cannot thrive in the midst of an incongruous amalgam between tribe and nation, magic and reason, modernity and tradition.

In the poisoned hybridities that make up Nigeria’s national culture, good art is still essentially tribal, i.e., relies on tribal motifs. Thus, the most successful works of art that are now appropriated as national art are rooted in tribal histories, cultures and mythologies e.g., Achebe’s Things Fall apart, Soyinka’s Death and the King’s horseman, or the Benin bronze mask that served as the emblem of Festac ‘77. This is so because that nation that was supposed to supplant the tribe by triggering cultural evolution to the higher, more universal rational-scientific worldview and culture, botched that historic task. Rather than seek to transcend the tribe, the postcolonial nation merely rehabilitated and aggregated tribal cultures as foundation and vehicles of national consciousness. In the neurotic state of national culture as the struggles with incommensurate realities, only quack arts like Nollywood tend to thrive. Nollywood for instance thrives because it decks itself as the continuation and radicalization of the Festac spirit of cultural nationalism. Drawing mostly on the unfinished pagan jujucentric worldview that is perhaps the only common denominator among the otherwise disparate tribes, Nollywood continually mines and re-activates the archaic treasures of magic and sorcery for themes and motifs and dread-filled symbols which resonate directly and performatively with the unevolved old tribal drives and instincts of deep traditional Africa. Nollywood thus leverages, essentially for quick commercial gains, the massive and overwhelming persistence of magic and superstition in the collective consciousness to concoct cheap artless melodramas including tales of money-making rituals and other primitive cultic blood sacrifices. The aim is to discredit modern reason or rational ethics [seen as the white man’s thing] by dramatizing stories which demonstrate the superiority of African magic and its occult shortcut to wealth, fame or political victories. In other words, forces hidden beneath Nollywood’s gory tales of magic and witchcraft are the dark, dangerous old ancestral ways that are no longer congruent with the cultural performatives of progress, reason and humanness. Yet in Nigeria Nollywood is celebrated as the third largest movie industry in the world and the government even brags about Nollywood’s contribution to the nation’s GNP. But Nollywood’s net contribution to moral/aesthetic progress has been wholly in the negative. The virulent recrudescence of cultic killings and ritual human sacrifice in Nigeria, the return of the archaic disregard for the sanctity of human life all over the country may not be empirically linked to Nollywood. But Nollywood’s energetic cinematographic work in glamorizing African juju, making the magical the quintessential African power, lavishing all its meagre artistry in making old ancestral technologies of evil attractive again, all in the name of African culture, point to Nollywood’s subliminal involvement in the defeat of reason, morality and modern logic in Nigeria. However, the success of Nollywood, despite all its obvious crudities, as the sole form of movie culture in Nigeria actually says more about the destiny of modern art in Nigeria than about the innate value of Nollywood itself. The success of Nollywood actually confirms that only the sick, crude, aberrant and ugly forms of modern art which directly mirror the inner depravities and incongruities of the Nigerian nation can grow here. The sick and perverse multi-tribal national soil seems programmed to repel good, beautiful and coherent creations of the imagination.

Perhaps the only exception to the abortion of national art in Nigeria is the protest and revolutionary music of Fela. But even here a closer study reveals that Fela owes his aesthetic originality not really to the angry lyrics denouncing the endless shenanigans of successive Nigerian rulers. On this score, Fela the political musician is now mostly an outlandish curiosity. But the originality of his Afro-beat aesthetics which has ensured the survival and trans-cultural appeal of Fela’s music, is not really the product of a national culture but derives mostly from his peculiar synthetic artistic genius. The Afro-beat genre drew on many influences and sources but mostly on his exposure to Jazz and other forms of contemporary music during his student days in London. The Jazz-inspired instrumental music anchored in heavy drumming, guitar works, saxophone and multiple horns etc. seems to carry the trans-cultural genius of Fela’s music. The political lyrics provides the charm of the local appeal but these as said earlier are dated just as his defiantly outrageous life-style, including exhibitionist sex, 22 wives , open drug use etc are now mere biographical curiosities.6

Program wydarzeń odbywających się w ramach Festacu w 1977 r.

The National Theater, an allegory of the abortion of nation and modernity.

Just like the nation was super-imposed on unconverted tribes and religions, the National Theater was built on an unmodern, neo-traditional socio-cultural environment. Its successive misfortunes stem from this attempt to build a modern art institution on a soil not prepared for it. Maybe, in keeping with the spirit of Festac, we should have built an enlarged neo-primitive juju shrine, not a modern theater. The latter presupposes not just a rationalized socio-cultural environment, but a well-developed rational management and maintenance culture, which is clearly non-existent in our heavily Africanized national environment. Thus, when the national theater has been successively allowed to rot and its surroundings overgrown with tropical bushes, it is not really that we do not appreciate art, modern architecture and modern art institutions; it may be just that our deeply embedded cultural nativism is barely compatible with both the spirit and practices of modernity. While our cultural Afrophilia has us still yearning unconsciously for the lost aesthetic primitivism of spontaneous fusion with nature around us, the spirit of modernity also in our midst continues to warn us that life in the ancestral state of nature is no longer the most appropriate life for man in the 21st century. It constantly reminds us that we cannot be truly modern and harvest the riches of modernity unless we considerably extract ourselves from ancestrality. Does Nigeria heed the call of modernity or does it continue to hearken to the Festac-inspired ancestral summons back to our roots? Apparently, the only thing worse than choosing which call to obey is trying to obey both calls at the same time. It is called serving two masters at the same time. We call it postcolonial hybridity. But in Nigeria, hybridity is a sickness and a major source of the chaos, disorder and confusion blighting national life

Today, the proposed sale of the National Theater speaks to the apparent impasse of modernity and its institutions in Nigeria. Selling the national Theater appears to be a desperation act by a nation caught in the evolutionary trap of trying to modernize and grow the nation not by instrumentalizing science and technology but by hanging on to the anti-progress elements like tribe, magic cults and traditional cultures. Reason dictates that a more economical path would consist in extracting the nation from many forms of nativism. Selling the theater rather than recognizing the unpleasant facts behind its dysfunctionality is in a way an admission of the wrongness of the African path to cultural and political development. It means we have given up on modernity in Nigeria, for we cannot manage it here. We are saying that modernity as culture art and politics cannot grow on our pathologized postcolonial soil.

Indeed, through official policies on art and culture, the Nigerian government itself unconsciously acquiesces in the continued defeat of modernity and rational evolution of the Nigerian nation. Post-Festac government policies actively promote and encourage the preservation, protection and flourishing of the divergent multi-tribal cultures of Nigeria. Two related policy instruments confirm this. The first is the setting up of a national institute of for cultural orientation, NICO, a body charged with the responsibility of ensuring the survival, preservation and activation of the various divergent ways, belief systems, customs and ancestral values of all the tribes. The second is the organization of yearly cultural festivals, a kind of mini-Festac, to celebrate and showcase the well-preserved and protected tribal cultures. In this politics of unconditional cultural protectionism, the government is convinced that it is excavating Africa’s original values for use as foundation of an endogenous, or African path to development [as opposed to development copied from the neo-colonial West]. However, by so doing the government is actually giving free rein and validating the very dark fissiparous tribal forces pulling the nation in mutually opposed directions and holding back the nation’s capacity to modernize and develop in an orderly rational fashion. Thus, when the state wonders that everyday there are reports of human sacrifice, horrid widowhood practices, money rituals and several other cultic irrationalities, it should bear in mind that that these acts are committed by citizens who, in obedience to government’s cultural-nationalist agenda, have decided to go back to their tribal ancestral roots to explore and re-use ancient pagan technologies of occult power, wealth or harm to personal or political enemies. If these people have turned away from reason, science as well as other cumbersome procedures of modernity, it is probably because they have been encouraged or persuaded by government cultural protectionism to believe that reason and science being the very forces of colonial violence against Africa, are not good enough for us; these foreign imports are not African enough. Hence the generalized disbelief or insufficient belief in the tools and resources of modernity for the purpose of personal or collective advancement resulting in the massive return to magic, sorcery and other occult rituals in modern Nigeria, may be just one unforeseen but logical outcome of the hypertrophy of cultural Africanism all over Africa. This militant Africanization of everything seems to have choked and badly damaged the already meager modernity heritage left by colonial education. [Colonial education, no matter how we malign it, was supposed to serve as the best cultural ladder to modernity].

Beneath the feel-good Afrocentric message of the Festac imperative to protect and defend our cultural heritage lies the irrational and counter-evolutionary impulse to re-activate and re-legitimize the many dark and dangerous forces of tradition that should rightly have been suppressed or sublimated in the interest of Africa’s ability to grow and develop. As Nigerians since Festac get over-exposed to the back-to-our roots cultural message, some ended up believing that reason and the scientific worldview, rational order and discipline are exclusively for whites, while juju, magic and irrational native spontaneities are quintessentially African. Nollywood and other forms of popular art translate this Afrophilia into digestible popular slogans or stories which show off tradition defeating modernity, magic trumping science and juju ritual rubbishing hard work.

Conclusion

I have read the misfortunes of the National Theater as the allegory of the deeper unpleasant truths that over-determine the abortion of nation, modernity and modern art in Nigeria. The question is why is Nigeria so structurally prone to the distortion and defeat of all that ensures progress and development of nations in the 21st century? Though the answer or answers may lie in a more detailed sociology of modern Nigeria, there is a possibility that finding the roots of the national question in Nigeria may involve understanding the essential Afrophiliac structure of the modern African mind generally. The Afrophiliac mind-set, [a combination of nativist narcissism and national-colonial paranoia,] which drives elite thought and action in Africa, was invented to shield us from the racist assaults of colonial Europe. But it ended up becoming the only way we see ourselves, Africa and the world. Unfortunately, Afrophilia has blinded us not only to the many self-inflicted unpleasant facts of our postcolonial condition, but also to many resources available in modernity for rescuing Africa from itself. Above all, it has made it virtually impossible for us to see the post-colonial nation as an experiment rather than a religious formula. Nigeria is only just an enlarged version of the Afrophiliac disease.

BIO

Denis Ekpo is a Professor of Comparative Literature and the Director of the Comparative Literature Program, at the University of Port Harcourt. A cultural theorist he has developed the concept of Post–Africanism. He was a member of the advisory board for Third Text from 2004 to 2012 and is the author of two books: Neither Anti-imperialist Anger nor the Tears of the Good White Man (2005) and La Philosophie et la littérature africaine (2004). He has participated in many art projects and is currently working on a Manifesto for Post-African art.

[1] The full meaning of the acronym FESTAC is Second World Black and African Festival of art and culture. The first such event held in Dakar, Senegal in 1966 was titled ‘festival mondial des arts negres’. For more on Festac see Denis Ekpo, ‘Culture and Modernity since Festac’77’, Afropolis, City Media Art, edited by Kerstin Pinther et al., Jacana Media, Johannesburg 2010.

[2] The issue was widely reported by national newspapers in November 2017.

[3] The Lagos Plan, 1980 or The African Path to Development was the first major blueprint for an independent African road map to technological and industrial development.

[4] See Ulli Beier, Contemporary art in Africa, Federick Praeger, London 1968.

[5] Patrick Chabal, Jean-Pascal Daloz, Africa works: Disorder as Political Instrument, International African Institute, London 1999.

[6] For more on the politics and aesthetics of Fela’s music, see Arrest the Music! Fela and His Rebel Art and Politics, by Tejumola Olaniyan, Indiana University Press, 2004.