A historic relic reconstructed from ruins – or a conservator’s fake? An example of postmodern thought ahead of its time – or a political propaganda gesture? How does one pigeon-hole Ujazdowski Castle, a building that goes back to the 17th century but was erected three centuries later? How does the building compare with others of its period?

Kanał Piaseczyński i Zamek Ujazdowski, 1919, Źródło: Łazienki Królewskie w starej fotografii, Wydawnictwo Bosz, Warszawa 2014 s. 78, zdjęcie w domenie publicznej, Wikimedia Commons

The Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA) is not a neutral place. “This is not some white cube, erected in a city but rather a place with multiple connotations,” commented Małgorzata Ludwisiak, director of the CCA, in one of her interviews. The Ujazdowski Castle, the seat of one of Poland’s key institutions presenting contemporary art, has little in common with other museums. The differences are many – from the very form of the building and its unusual history to how it is perceived today. If one looks at the building in the broader context of architecture in Warsaw and Poland, it transpires that the Castle is not a close fit to any other edifices in the capital.

Complacent about the architectural achievements of recent decades, we now expect a museum to be more than just a space for presenting works of art; today, the very building that houses the art is itself an exhibit. Contemporary museums are strikingly attractive and original designs that stand out from their surroundings; their very appearance draws in crowds of visitors. More than that – spectacular museum buildings have been taken for granted to the extent that too-modest a project can cause an outcry. One notable and obvious example is the memorable competition for the seat of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw in 2007, when, after an understated proposal delivered by Christian Kerez had been selected as the winning design, criticism of the decision led to the dismissal of the then-director of the Museum, and after five years of agonizing disruption, the city council finally withdrew the architect’s commission. It is no exaggeration to say that today, museums are more often mentioned as architectural objects than as places where art is collected or presented.

Naturally, it has not always been the case that museum buildings functioned as a city’s iconic landmarks. Before 1997, when Frank Gehry built his extravagant Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao – which, according to widely publicized legend, transformed the fate of that provincial Spanish city and became an example to emulate – museums, including those devoted to contemporary art, had been housed in buildings that were as elegant as they were understated, inspired by the architectural styles of past epochs, or else severely monumental – since these were the stylistics considered appropriate for these “temples of art.” Examples that spring to mind are the National Museums in Krakow and Warsaw, built in the 1930s on the wave of the resurrection of nationalism that accompanied Poland’s regained independence: mighty stone edifices, cold and strikingly solemn. Within this somewhat simplified classification, one ought also to mention a third category – museums that have been accommodated in customized pre-existing buildings that had been used for other purposes. The National Museum in Wrocław is one such example from the past – in 1948, the museum was housed in the former Silesian regency office built between 1883–1886 in the Dutch Renaissance style. Also in the city, in 2011, the Wrocław Contemporary Museum found a temporary home in a free-standing anti-aircraft bunker built during World War II. The Silesian Museum in Katowice is located in a defunct coal mine; MOCAK in Krakow was built on the site of Oskar Schindler’s enamel factory and incorporates elements of the original building, and Elektrownia, the Masurian Centre of Contemporary Art in Radom, has been housed in a former power station.

How does Ujazdowski Castle fit into this classification? It is hard to call it an iconic building, nor can it be viewed as a monumental temple of art, and it does not quite fit the bill of an institution housed in an adapted historic building. The building that houses the CCA does not slot easily into any of these types of traditional museums. Indeed, it is a phenomenon full of contradictions. Although Ujazdowski Castle is considered a historic building, in reality its construction dates back only to the post-war era. Although it is on the Royal Route, it lies at the periphery – not only is it not visible from the street but is hardly ever referred to in conjunction with the other historic buildings that are part of the Route. Although, in contrast to other buildings in Warsaw, the Castle had survived in relatively good shape, it was, nevertheless, demolished, and rebuilt in the 1970s, in the spirit of a concept of conservation that was outmoded even then. Its interiors, stylized as 18th-century, house artistic experiments of the 21st-century, which were made possible thanks to the activities of an institution that was created shortly before the introduction of Martial Law in Poland in 1981.

Ujazdowski Castle is rarely discussed as an architectural object per se or as an instance of its specific conservation approach. It is hard to know whether this is due to its – literally – off-the-beaten track location, or the fact that the narrative of the building has taken a back seat to the artistic events that take place there. Or perhaps, it is simply the case that today, when the trend in Warsaw is to destroy rather than to rebuild and restore historic relics – and such decisions are ever more frequently in the hands of developers rather than municipal conservators, the time is now being forgotten when, in Warsaw, contrary to international conventions for the preservation of architectural legacy and in full awareness of the conservation falsehood being committed, the operation of recreating the historic fabric of the capital from the post-war devastation and ruin was initiated. The reconstruction of Ujazdowski Castle, although carried out only in the latter part of the 1970s, also arose from the same philosophy that had informed the reconstruction of Warsaw’s Old Town, which was articulated in the words of Jan Zachwatowicz, spoken during the National Conference of Art Historians in Krakow in August 1945: “We cannot accept that cultural monuments be wrenched away from us; we shall reconstruct them, rebuild them from the foundation stone upwards so as to pass on to the next generations, an, if not authentic, at least faithful replica of these monuments […]. Our sense of duty towards the generations to come demands that we rebuild what has been destroyed, in a full reconstruction, fully aware of the tragedy of the historical falsehood thus committed”; Zachwatowicz insisted that this course of action was not the creation of a new conservation policy but was, rather, “merely embracing a method of action in singularly dramatic circumstances.”

What is then the history of the Ujazdowski Castle? Its origins on the Vistula embankment date back to the 13th-century, when Jazdów was a fortified city that belonged to the Dukes of Masuria. King Sigismund III Vasa built a castle there at the beginning of the 17th-century and later that century the building was rebuilt to the design of Tylman from Gameren. The building changed hands many times, for example during the 1720s, the Lubomirski family leased it to king Augustus II. It was during his time that the Royal (also known as “Piaseczyński”) Canal was built – a crucial piece of water engineering providing a waterway from the bottom of the embankment on which the castle stands towards the Vistula. In the second half of the 18th-century, King Stanisław August Poniatowski engaged architects in order to carry out alterations to the building which he had bought as his private residence. At that time, the castle was incorporated into a new urban layout, known as the Stanisław Axis, a route that included today’s Politechnika, Zbawiciela, Unii Lubelskiej, and Na Rozdrożu squares. In this manner, the king, eager to follow Parisian urban design, wanted to link his residence to the city. After the First Partition of Poland, faced with the dramatic transformation of the country, the king transferred Ujazdowski Castle to the army, and until the end of World War II, it remained in the hands of the military – in turns, the Polish, Prussian, and Soviet armies. The old annexes were partially demolished and parts turned into army barracks; more sprung up on the surrounding land and, from the beginning of the 19th-century, some were used as hospitals. As early as 1818, the Central Military Hospital had been founded there and both during World War I and between the wars, the castle functioned as a hospital. In 1944, Ujazdowski Castle burnt down. Its walls did, however, survive, and alongside the barracks, stood until the 1950s.

Since the castle had survived the war in a relatively good state, in 1945 it was supposed to be adapted for the use of the Faculty of Architecture of the Warsaw University of Technology – but nothing came of the plan. In 1947, President Bolesław Bierut considered creating a residence for the head of state in the castle. In turn, in 1953, the winning design of an architectural competition proposed transforming the building into a multifunctional Soldiers’ House, also doubling as a cultural center with an adjacent park for the masses, and the building of an amphitheater. Józef Sigalin, who was on the management team of the Bureau for the Reconstruction of the Capital and chief architect of Warsaw, co-designer of the East-West Route in the capital and the MDM residential estate, author of a three-volume history of the city Warszawa 1944–1980. Z archiwum architekta (Warsaw 1944–1980: From an Architect’s Archive), thus records therein the recommendations of a meeting of the Executive Council of the Bureau for the Reconstruction of the Capital: “to deem the environment of the Piaseczyński Canal between Czerniakowska and Ujazdowski Castle as in need of rehabilitation and to open it to the public; to designate Ujazdowski Castle for cultural uses linked to culture for the people (reading rooms, libraries, exhibitions etc.); to allocate appropriate funds for the rebuilding of the basic structure of Ujazdowski Castle and to put in good order its external elevations as well as clear the land in its immediate vicinity so as to make it accessible from the Na Rozdrożu square.”

At that time, the desire to reconstruct Ujazdowski Castle and endow it with a new purpose was nothing out of the ordinary. After all, Warsaw’s Old Town was being rebuilt as were the buildings of the Royal Route – a huge and unprecedented venture. The historic part of Warsaw was being recreated (or rebuilt in a historic style) from the ruins – for political, propaganda and emotional reasons – at the expense of historic monuments in other cities. The rebuilding of hundreds of buildings in the capital’s former center followed. Although for a brief moment after the war, there was a question mark over the reconstruction of the former capital, 70 percent of which now lay in ruins – and the idea of moving the capital to Łódź, a city that had survived almost intact (apart from the Jewish quarter) was seriously considered – in the end the “reconstruction faction” won the day, standing strong against the “modernists,” who saw the annihilation of the city as an opportunity to rebuild it to a new vision. The leading figure amongst the reconstructors was Jan Zachwatowicz. This reconstruction was not a recreation of the pre-war status quo but rather an implementation of a certain vision of historic relics, as can be easily demonstrated. After the war, the façade of St John’s Cathedral acquired a look “inspired” by the Wrocław Gothic style. The designer, Zachwatowicz, based it on records referring to the fact that, many centuries earlier, it had been architects from Lower Silesia that had designed the building. Zachwatowicz paid little heed to the 19th-century reconstruction of the cathedral or the numerous previous interventions in its appearance. Neither did the first quadrant of the construction to be erected from the ruins – that is to say Nowy Świat Street – regain its previous appearance. Zygmunt Stępiński who was in charge of the project decided that the post-war reconstruction should consolidate the, previously higgledy-piggledy, appearance of the tenement blocks, investing them with the classism of Congress Poland; he opted for that period as the period of Warsaw’s greatest prosperity. Similarly, Mariensztat, a small residential settlement next to the East-West Route, was to become a place of bucolic bliss in small-town style. Although these creations were based on historic styles, they were an impression, a riff on the previous appearance of the locations. The old historic buildings were being recreated from the ruins, yet given new functions: the old residential houses in Warsaw or Gdańsk (the second city to have experienced historic-style reconstruction after the war) were to become residential, so the offices or the interiors of the blocks were not recreated. This is particularly obvious in Gdańsk, where between the street frontages there were large courtyards left – in some, there was room for nursery school buildings or medical centers. Piotr Majewski – who in his book Ideologia i konserwacja. Architektura zabytkowa w Polsce w czasach socrealizmu (Ideology and Conservation: The Architecture of Historical Renovation in Poland during Social Realism) compiled the discussions carried out throughout the country about the future of ruined historical buildings – comments that Polish conservators were suffering from a kind of “split personality,” in trying to combine an “academic” and a “visionary” approach. Majewski stressed that “After the reconstruction, historic buildings and municipal centers looked different than before. They were contemporary creations based on historic concepts, and were part of the history of the architecture of the 20th century.”

Powojenny układ urbanistyczny Głównego Miasta w Gdańsku, fot. Bazie , CC BY-SA 3.0 pl Wikimedia Commons

Stare Miasto w Warszawie z lotu ptaka, lata 60., źródło: Plan generalny Warszawy, Prezydium Rady Narodowej miasta stołecznego Warszawy i Rada Główna Społecznego Funduszu Odbudowy Stolicy i Kraju, Warszawa 1965, s. 29, zdjęcie w domenie publicznej

Widok Placu Zamkowego w Warszawie, II połowa XIX wieku; autor: Charles-Boris de Jankowski, źródło: www.classicartpaintings.com, PD-Art Wikimedia Commons

Ulica Nowy Świat w Warszawie na wysokości ulicy Ordynackiej, widok w kierunku Alej Jerozolimskich, przed 1939 rokiem; źródło: Andrzej Jeżewski, Warszawa na starej fotografii, Wydawnictwo Artystyczno-Graficzne, Warszawa 1960, p. 96, zdjęcie w domenie publicznej, Wikimedia Commons

Although the reconstruction of Warsaw, carried out immediately after the war, stood in opposition to established concepts of conservation prevalent in the world, it was acknowledged as an exceptional and praise-worthy enterprise. Warsaw’s Old Town became one of the youngest architectural objects to be put on the UNESCO World Heritage list, due precisely to its merit in the reconstruction of historic form. At the same time, in Rotterdam, Le Havre and Cologne, cities also destroyed by bombing, modernist urbanizations and public edifices replaced the historic districts; the norm in Europe was to raise from the ruins no more than individual buildings, those deemed the most precious. The trend became policy, and so in Poland, at the turn of the 1950s and 1960s, the Charter of Venice was agreed – the International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites. This document, finally signed in 1964, introduced the regulation of the preservation of historic relics; amongst others, it prohibited the reconstruction of historic objects, and also the principle that any new elements introduced into a historic building should be made clearly distinguishable from the original ones. Interestingly, it was Jan Zachwatowicz who signed the Charter on behalf of Poland. The reconstruction of the Old Town in Warsaw had to be done not so much out of necessity as much as due to the political situation. To raise the heart of the city from the ruins was intended to emphasize the might of the nation, the continuity of Polish statedom and to become a symbol of the renovation following the tragedy of the war. In other cities, the scale of historical reconstruction was much smaller in comparison. After the “Thaw” (political liberalization) of 1956, the new de rigueur blueprint was to build new residential settlements to replace the former “old towns,” particularly in the cities that were historically considered more or less German – thus cities in the so-called Recovered Territories, or the former Prussian lands – such as Malbork, Słupsk, and Szczecin, or in Lower Silesia. Notably, some of these constructions are conceptually very interesting examples of modernism. One is the small estate of residential blocks erected at the foot of the Teutonic Knights’ Castle in Malbork to the design of Szczepan Baum; another is the multi-family houses around the Castle of the Pomeranian Dukes in Szczecin, in which the form of prefab blocks was combined with elements that referenced the tenement blocks that stood there before.

Osiedle w sąsiedztwie Zamku Książąt Pomorskich w Szczecinie, fot. Anna Cymer

Osiedle w sąsiedztwie Zamku Książąt Pomorskich w Szczecinie, fot. Anna Cymer

Osiedle w sąsiedztwie Zamku w Malborku, fot. Anna Cymer

For nearly a decade after the war, Ujazdowski Castle remained on the list of objects earmarked for reconstruction. Although there were a number of designs, none definitive, what was being taken for granted was that if the castle was to be reconstructed, its form would be historical. It is not entirely clear why in 1954 the burnt-out ruins were razed to the ground. Perhaps the generals were behind the decision – they may have wanted to build the Polish Army House there as a brand-new building, and the castle was in the way. The fact remains that the building was demolished at a time of great political turbulence, directly before the “Thaw” – following which, any reconstruction was no longer possible.

What, then, happened, for the building to be recreated, after all?

Two events coincided in the early 1970s, which turned out to be crucial for the future of Ujazdowski Castle. On 20 January 1971 the decision was undertaken to reconstruct the Royal Castle, the only building in Warsaw about which already in 1945 there had been no doubt that it ought to be reconstructed – as even the “modernists” agreed, but which had, however, not been rebuilt at the same time as the Old Town. For this to happen, a political change had first to take place at the highest level: Władysław Gomułka, the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party, had been against the reconstruction, whereas his successor Edward Gierek saw such a project as an opportunity to improve the popularity of his government. A large team set about the implementation of the scheme. It was headed by Jan Bogusławski, Irena Oborska and Mieczysław Samborski, and supervised by the Citizens’ Committee for Reconstruction, which comprised the Scientific Commission (with its chairman Stanisław Lorentz), the Archaeological Commission (chairman Aleksander Gieysztor), and the Architectural and Conservationist Commission (chairman Jan Zachwatowicz). The task at hand was not an easy one: through the centuries, the Royal Castle had been rebuilt numerous times. Yet again, a quarter of a century after the end of the war, the dilemma from the time of the rebuilding of the Old Town raised its head again: which version of the building was the most valuable and worthy of reconstruction? The solution that was settled on was an unusual compilation. Wanda Puget, who has researched the history of the Royal Castle, described it thus: “[I]t was decided that the most valuable elements from specific historical epochs [would] be highlighted, with special emphasis on: the gothic Great House with its Renaissance rooms on the ground level, the 17th-century monolith forming a pentagon with the Sigismund and Władysławów Tower and the City Gate, together with the 17th-century corner turrets and dormers according to seventeenth- and 18th-century designs. As regards the interiors, special attention [would] be paid to the restoration of the Stanisławów halls.” Another project, thanks to which also the restoration at Jazdów could be embarked on, had quite a different character. In 1968 the foundation was laid for the future Łazienki Route, which only began in earnest in 1971. It was implicit from the start that this would be an opportunity to carry out some projects in the neighborhood. These turned out to include the small Ustronie square next to Aleje on the Embankments, the sports center at Cypel Czerniakowski, the park in Pole Mokotowskie, and part of the Prague Boulevard. The largest-scale of these renovations, however, was the rebuilding of Ujazdowski Castle. In charge was Piotr Biegański, one of the founders of the Bureau for the Restoration of the Capital, between 1945 and 1954 Warsaw’s conservator-in-chief, the man behind the restoration of the Staszic Palace, the Kazimierz Palace and the buildings on Bankowy Square in Warsaw. It was Biegański who made the decision to return the building to its appearance in the first half of the 18th century, during the rule of the Sas dynasty; it was also he who had to opt for one of the versions of the Castle, which had undergone numerous modifications. During the restoration, the surrounding area was cleared and the baroque stairway down the embankment was rebuilt, as was the Piaseczyński Canal. Józef Sigalin, the chief designer for the construction of the Łazienki Route, in charge of the project, commented at the time, “the burnt-out but otherwise well-preserved remains of Ujazdowski Castle had been demolished a few years later, its foundation was painstakingly restored so that one day – now – Ujazdowski Castle could be rebuilt as it had been, more beautiful and historically truer than it was before the war.”

Kanał Piaseczyński, widok z ul. Myśliwieckiej w kierunku Zamku Ujazdowskiego, 2017, fot. Adrian Grycuk, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Zamek Ujazdowski od strony skarpy wiślanej, 2009, fot. Nikolaus von Nathusius, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The future role of the building had not at that stage been decided, although it was certain that it would be to promote culture. Apparently, Henryk Buszko, the chairman of the Association of Polish Architects (SARP) during 1972–1975, wanted the Castle to become an Architecture Center. Finally, however, by a decision of the Minister of Art and Culture taken in October 1981, it would be the Centre for Contemporary Art that in 1985 took up residence in the restored building.

Two-story and built on a square plan, with corner towers (and today, also with a side annex) it has become one of the most important places on the artistic map of Poland. This is not a typical historical pile, and evades simple classification. Today, there are different takes on its restoration. The orthodox conservator considers the building simply a piece of fakery, a pseudo-relic that presents a historic lie. Some, more progressive, observers, are inclined to view the Royal and Ujazdowski Castles as… postmodern erections, which have grown out of a wave of opposition to the authoritarian order and the geometry of modernism and a return to the styles of the past. Is the restoration of the edifice in Jazdów closer to the lofty goal of raising Warsaw’s Old Town from the ruins – or to the Przemysł Castle in Poznań, a modern fiction, built in recent years on the basis of scant archival material, and ineptly stylized as medieval? Fans of Sas Castle in Warsaw tend to hail the Ujazdowski Castle story as a successful, contemporary example of the restoration of a historic relic, an endeavor unrelated to the post-war propaganda of the “great task of the rebuilding.” Prof. Jacek Purchla, an art historian and founder of the International Cultural Centre in Krakow, explains the rebuilding of Ujazdowski Castle by the impotence of Polish communist governments: “In terms of architecture, the policy of People’s Poland was dominated by the need to maintain the inherited stock, reconstruct war-damaged buildings, and adapt existing structures for new cultural needs, [and less committed to] new architecture. An officially hallowed example of re-building was the Centre for Contemporary Art located in the reconstructed Zamek Ujazdowski (Ujazdowski Castle) which opened in 1985. [T]he Ujazdowski Castle reconstruction exemplifies not only the mania for reconstruction so characteristic of People’s Poland, but above all the inability of the communist state to create iconic architecture, including that built for cultural purposes; a true paradox given the level of financial investment in the realm of culture during the 1970s and 1980s.”1

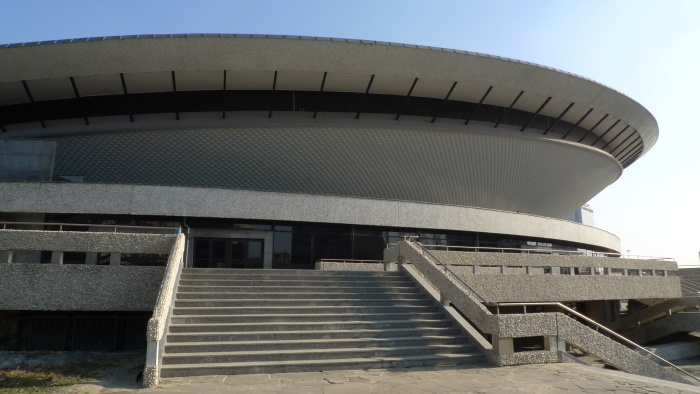

Hala widowiskowo-sportowa Spodek, Katowice, fot. Anna Cymer

Kieleckie Centrum Kultury, Kielce, fot. Anna Cymer

This is a controversial viewpoint, as it is difficult to find many manifestations of “reconstruction sickness” in the architecture of the People’s Republic – during the post-war decades, it was only in the first few years that a broader reconstruction of historic buildings was undertaken. And it begs the question as to whether real existing socialism was indeed unable to generate icons. What about the Palace of Culture in Warsaw, the Spodek Building in Katowice or the Hala Olivia in Gdańsk? And it was during the second half of the 20th century that many cultural buildings sprang up in Poland – not necessarily large-scale, but often architecturally intriguing projects, such as the Art Bunker in Krakow, the Cultural Centre in Kielce, the Poster Museum in Warsaw, the Upper Silesia Cultural Centre in Katowice, the Philharmonic in Częstochowa, the Dramatic Theatre in Opole, and so on. It goes without saying that the concept behind Ujazdowski Castle is at the opposite end of the spectrum to the contemporary, modernist and often formally daring buildings of the 1960s and 1970s.

Kościół Rodziny Rodzin pw. Matki Boskiej Jasnogórskiej przy ulicy Łazienkowskiej w Warszawie (kościół Monastycznych Wspólnot Jerozolimskich pw. Matki Bożej Jerozolimskiej), fot. Wistula, CC BY 3.0 Wikimedia Commons

Kościół Rodziny Rodzin pw. Matki Boskiej Jasnogórskiej przy ulicy Łazienkowskiej w Warszawie (kościół Monastycznych Wspólnot Jerozolimskich pw. Matki Bożej Jerozolimskiej), fot. Anna Cymer

Or, is it indeed the case that, from today’s perspective, Ujazdowski Castle should be classified as a modernist design, ahead of its time? We are familiar with buildings in which motifs and details drawn from historic styles have been employed in an almost literary manner – such as the Church of Our Lady of Jasnogóra Family of Families on Łazienkowska Street in Warsaw, or the Church of Mary, Queen of Poland, in Głogów (which even its architect, Jerzy Gurawski, refers to as a “little Wawel”), and the infill residential blocks erected in Poznań and Wrocław during the 1980s, on whose façades there are anachronistic details, anything from the baroque to art nouveau. There is no single answer as to where Ujazdowski Castle fits into the history of architecture. Interestingly, the issue rarely surfaces in debates about history and new urban planning of the capital. The exception was the year 2008, when it was announced that the Museum of Polish History would be built on a deck spanning the Łazienki Route cutting. This controversial idea again drew attention to the existence of Ujazdowski Castle; experts pondered whether the new object would interfere with the capital’s cityscape, destroy the existing promenade routes along the boulevards (for example between Agrykola and Jazdów) or overpower the CCA building. Some expressed the opinion that Ujazdowski Castle would be overshadowed by the contemporary bulk of the newcomer; others felt that the Museum of Polish History would revitalize the area and bring fresh blood to the neighborhood – also to the benefit of the CCA. An international competition was announced for the design of the Museum of Polish History (MPH). The award went to the vision submitted by the studio Architectes Paczowski et Fritsch from Luxembourg. Bohdan Paczowski’s team put forward a quite simple building, with a mass of glass and a sparse, almost minimalist form. The director of the Museum of Polish History, Robert Kostro, praised the design, claiming that it provided a “chance to set off the objects that surround the building of the MPH. […] It is very important not to overshadow or dominate Ujazdowski Castle […], so that the Castle may become the chief ‘exhibit’ of our Museum.” Although, since March 2015, we have known that the MPH will not be built over the Łazienki Route (as it is now being built at the Citadel), it is important to take note of the view of Robert Kostro, who treated Ujazdowski Castle as a precious relic of the past.

Today, more than 30 years after the Centre for Contemporary Art opened in Ujazdowski Castle, the function has overshadowed the form of the building. It seems that the exhibitions and events that take place there have a greater presence in the public eye than the “historic value” of the seat of the institution. It is, nevertheless, important to be aware of the many semantic layers that lurk within the edifice that rises over the Vistula embankment and of its unusual history; with its origins in the 17th century, this is a hybrid of the baroque architecture of the Sas Dynasty era and the architecture of the 1970s.

Translated from the Polish by Anda MacBride

BIO

Anna Cymer is an art and architecture historian with a research focus on modern and recent architecture. Ministry of Culture and National Heritage grant holder; her book on the Polish architecture of the second half of the 20th century is due out in 2017 by Centrum Architektury.

Cover photo: Piaseczyński Canal (Royal Canal) and Ujazdowski Castle, 1919, Source: "Łazienki Królewskie w starej fotografii", Wydawnictwo Bosz, Warsaw 2014 p. 78, public domain, Wikimedia Commons

1 Form Follows Freedom. Achitecture for Culture in Poland 2000+, trans. J. Taylor Kucia, J. Chodakowski, T. Bieroń; ed. J. Purchla and J. Sepioł, International Cultural Center, Krakow 2015, p. 24.