The cinema saves the worldview and photographs the state of soul. The filmmaking’s annalistic role has been observed since the very beginning of cinematography; the possibility to record a fleeting moment tempted the next generations of chroniclers who then grabbed a camera to capture a piece of the world. Did they realise the role these moments, frozen in time, will play for succeeding generations of viewers? Film stories speak to us not only through the entirety of days gone that one can see in them, but they convey the spirit of the ones behind the camera; those who fought to preserve this particular image, those who decided to tell the tale – a real one or fictional – in precisely this, and not the other, way.

Every single film (as well as each scene) constitutes a piece of mirror that its creators looked in. In order to ascertain that it is not a distorting mirror and it does not alter the image too much as well as try to understand what the preserved fragment is about, it is vital to compare a lot of such pieces. Those who are bound by the circumstances they were shaped in and those which can be combined, similarly to puzzles, into the social processes chronicle – zeitgeist.

An extremely interesting example of such a chronicle is 1980s Polish cinema. The suffocating times of moribund Communist regime, struggles with censorship, searching for channels that could enable independent art creation or just a chance at a decent living – all this was photographed in numerous films that came to be at that time. One can see shifts in public sentiment resulting from the political situation, different directorial visions that use distinct film genres’ poetics. Yet, looking at these cinematic shards laid side by side, a process of forming a community in Poland can be observed. They constitute a narration about the theme of the road that Polish society had travelled since the beginning of the decade. From martial law tragic events to the end of Communist rule in Poland, with the latter being considered to happen – conventionally and controversially – during the first partly free elections on June 4th, 1989.

I attempt to compose the image from a few pieces of the mirror, though many more titles could be mentioned as they played an important role in recording the 1980s in Poland.

The exhibition Nie ocenzurowano at the Center for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle, photo: Adam Gut

One of the martial law’s most critical consequences was stopping violently the developing Polish culture in its various manifestations. In the case of cinema, this was all the more tangible since the so-called “Solidarity” season, forming at the time, inspired subsequent creators empowered by the loosening of censorship restraints (short-lived, as it later turned out). Some even spoke of a “cinema boom”. The First Lady of film criticism, the head of Polish weekly “Film” – Bożena Janicka wrote the following in her report on Gdańsk Polish Film Festival in 1981:

Polish film seems to be on the threshold of a grand victory streak. A proper tone for important matters was found, many different opportunities opened up for one to take advantage from. If the circumstances are favourable.[1]

Tadeusz Lubelski points out how big of a sensation the Festival could have been if it had been organised in the following year:

If one were to take a feasible moment of particular films’ completion, here are the titles that should have made it and competed for the prizes: “Danton” by Andrzej Wajda, “Austeria” by Jerzy Kawalerowicz, “The Issa Valley” by Tadeusz Konwicki, “An Uneventful Story” by Wojciech Jerzy Has, “Konopielka” by Witold Leszczyński, “Blind Chance” and “Short Working Day” by Krzysztof Kieślowski, “A Lonely Woman” by Agnieszka Holland, “The Weather Forecast” by Antoni Krauze, “The Mother of Kings” by Antoni Zaorski, “Interrogation” by Ryszard Bugajski, “The Big Run” by Jerzy Domaradzki, “The Haunted” by Andrzej Barański, “Daimler-Benz Limousine” by Filip Bajon. [2]

None of the previous competitions included so many significant titles. Alas, the reality proved different. Along with the introduction of martial law, the production of over a dozen films was instantly halted and Film Groups activity was subjected to the so-called “verifications” that usually resulted in total suspension. The Communist authorities banned screenings of all leading films in Polish cinema, a great number of directors went abroad. A majority of those who stayed, especially actors, engaged in a “Jaruzelski TV” boycott. The film community, though heavily crippled, did not surrender. Screenings were organised in churches, home theatres were established. Film production was gradually resumed, although directors supporting the authorities were given precedence. The others were exposed to the unyielding restraints of censorship.

Let us start reviewing the fragments of the mirror with two films that were successfully finished before martial law introduction, and they stemmed directly from what had been going on in shipyards and factories during sixteen months of “Solidarity carnival”. “Workers ‘80” (dir. by Andrzej Chodakowski, Andrzej Zajączkowski, 1980), a full-length film reporting the strike that took place in Gdańsk Shipyard in August, 1980, was presumably the most anticipated by the audience documentary in the Polish cinema history. The film had been screened in some cinemas in throughout the country since December due to the pressure of Independent Self-Governing Trade Union „Solidarity”, an organisation registered just a few months prior to screenings. The picture could not be announced in the newspapers – there was only a mysterious phrase: “show booked”. Spontaneous and resolute statements spoken by workers in the film demonstrated energy, wisdom and determination, giving glimmers of hope.

An even bigger impact was achieved with “Man of Iron” (1981) – a film finished in a rush, within half a year, for Cannes festival – resulting from a collective commission submitted by Poles to Andrzej Wajda. The intention of it being to summarise the moment and tell the world what exactly happened in Poland. The tale of Birkut family fortunes, that is a sequel to Wajda’s magnificent “Man of Marble” (1976) directed five years earlier, is alleged to be quite formulaic, propagandistic even. In her essay on Wajda’s political cinema, Janina Falkowska pointed to the fact that if „Man of Marble” ironically refers to a nightmarish statue of the erstwhile shock worker whose triumph and fall is a matter which a tenacious female journalist wants to investigate, sarcastically juxtaposing pathos and grotesque, then “Man of Iron” is completely deprived of such sarcasm. There is no distance, there is no dialogue with socialist realism, where somehow its foundations are copied onto a black-and-white vision of the world. Most certainly, that is the price paid for the rush as well as emotional need of the moment.

There is no denial that Wajda accomplished a very accurate record showing was going on in the hearts of Poles back then. Our Polish “Citizen Kane” history (Wajda overtly follows the narrative structure of Orson Welles’s piece), investigated by radio reporter Winkel, does not only reproduce current events that entire Poland lived and breathed, but also presents how rooted they are in the past. It acknowledges causes and results, takes a closer look at the motivations of people on strike, as well as at those who denied participation in it. The film shows how lack of solidarity in trying times led to consecutive defeats. A scene that stands out in one’s memory is the one taking place during bloody riots, later to be called Black Thursday (17th of December, 1970) when students locked up in dormitories can hear cries of chanting worker crowd, marching through the streets. However, the students do not react to the call to join the strike. The grudge held against workers who did not support their protests in 1968 does not allow the society to unite.

And it was for these social divisions, the wounded pride, the supposed divergence of group interests fuelled by the authorities, the incomprehension of the common cause – freedom – all this photographed by Wajda. Though many lacked faith in open, yet peaceful actions against the authorities, more and more started to realise that only true solidarity can ensure that first glimmers of hope for a real change will appear. Maciej Tomczyk’s messianic figure, together with Anna Walentynowicz and Lech Wałęsa – portrayed as the mother and father of nascent national unity – being present at his wedding and blessing the union of heroes, still constituted uncustomary solutions in Polish cinema.

In a number of films made during that period one can see a broken society. The society which feels locked in the Communist regime prison, yearning for almost mythical freedom, yet lacking in belief that it could be achieved. Helpless. The only way to escape the Communist system cage seemed to be fleeing abroad. It is striking in how many various productions from those times a theme of trying to escape an enslaved country recurs; to leave Poland, maybe even forever. Attempts made with hope for a better life, a professional success, a change, a chance to breathe freely are all doomed to failure almost every time.

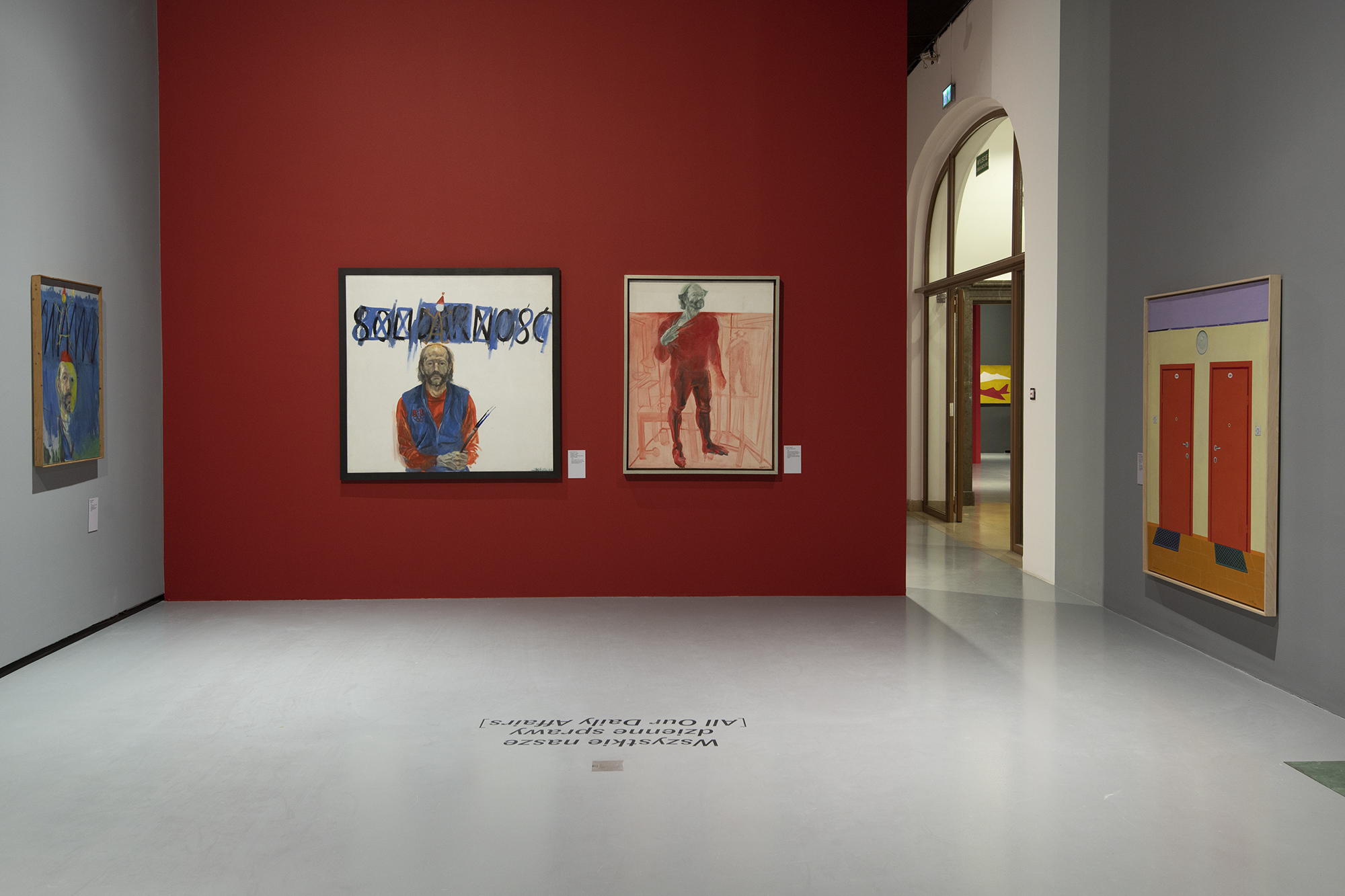

The exhibition Nie ocenzurowano at the Center for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle, photo: Adam Gut

The leading figure of Krzysztof Zanussi’s film “The Constant Factor” (1980) was one such character that tried to leave Poland. Similarly to his father, the protagonist wanted to go to the beloved Himalayas, but hateful colleagues had sewn dollars into his jacket so that he was stopped at the airport. Leaving the Soviet Union meant hope for starting a new chapter in a better, dream world for weary heroes in “A Lonely Woman” (1981, premiered in 1987) by Agnieszka Holland, but right before they are to pass the border, they lose control of their car and have an accident. Witek in “Blind Chance” (1981, premiered in 1987) by Krzysztof Kieślowski, wilfully attempts to leave the country and we can see that in all three versions of his fate – as a Polish United Workers’ Party activist, a dissident fighting against Communism and a stoic who is not involved in politics in any way – going abroad is practically within the reach of his hand. None of the three threads lead to a successful end. The system stifling people’s freedom proves omnipotent and its uncanny power appears to have a hold even over the plane that Witek boards in the last variant of the story. The machine explodes upon its ascent. The imagery of the scene was depressing for some, while others found it moralistic: if regardless of being polite and not getting involved, you cannot break from the prison, therefore maybe fighting is the answer? Over the years, this scene gained a new context that gave it a more prophetic meaning.

A successful escape takes place a couple of years later in the authentic story called “300 Miles to Heaven” (1989) by Maciej Dejczer, though it is paid for by suffering. In the final scene of a telephone conversation between brothers, who succeeded in escaping to Denmark by hiding beneath a lorry’s undercarriage, and their parents who never left Poland, there is a terrifying line cried by the heartbroken father: “Stay away from this place forever!”. Yet, the approach that moves the most, is that of Waldemar Krzystek, the “The Last Ferry” (1989) director. The film tells a story, also based on facts, about a passenger group leaving Świnoujście for Hamburg in the hope of a better life. During the very voyage, the martial law is introduced and the ship returns to Poland. The panic that follows due to a grim perspective of imprisonment, the desperate jumps into the sea just to break free from the Communist system, clearly show how deeply rooted characters’ yearning for freedom is. It was not merely a dream – it became similar to an animal instinct. A primitive impulse that strips many from dignity in a critical situation. Unleashes the will to sacrifice in others. This is precisely what decision about staying on the ferry and continuing their lives in shabby enslavement is for the main characters in the movie – sacrificing their own well-being and freedom in order to fight for liberty and common good.

The eighties films share the theme of immensely lost main characters. The distrust is seen in almost every production mentioned above, and it is skilfully burlesqued in a cult film “Teddy Bear” (1981) by Stanisław Bareja. The protagonists portrayed in the cinema of this period live among crawlers, opportunists and careerists who strive to achieve their goals with no regard for the fellow man. Without thinking about what is right and appropriate. How should a road to freedom be built in such a crippled society? The great mocker of the Communist-era absurdities, Bareja, decides to end his grotesque „Teddy Bear” in a curiously turgid manner – with a lofty monologue that addresses the basic values of a compromised community. The need to find a moral compass appears to be really strong in the cinema of those times and protagonists seek value systems, or authorities that represent these systems, in an almost desperate manner. Their uncertainty when deciding the right way is showed in the previously mentioned “Blind Chance” where misguided Witek, similarly to a supine sponge, is soaked with ideology that fickle fate has in store for him. A completely different tone can be observed in Zanussi’s “The Constant Factor” as Witold simply has a moral backbone, although he does not seem to be aware where the code of ethics he follows in his life comes from. As expected, choosing what is right and just instead of things that are easy and profitable makes more enemies than friends. Zanussi seems to ask: what kind of broken society do we live in, as there is no place for people pure of heart, people who are not touched by deceit, corruption and opportunism? But, since those people are scarce and yet they still exist among us, maybe there is hope even for such a broken nation?

The saddest diagnosis is given by Krzysztof Kieślowski in “No End” (1985) – a bleak tale that suggests suicide as a remedy to pervasive hopelessness. There is nothing strange about that, though; the film was made during one of the most devastating social crises that dashed hopes for any improvement of the situation. “No End” tells, among others, a story of a lawyer that attempts to defend in court a worker accused of leading a strike. When asked for motives behind his actions, the worker replies that he wants a better and more righteous life in Poland. The defender then asks him: “What Poland do you have in mind?”. “Our Poland, there is no other” – he hears in reply. “Can you imagine a different one?” – the lawyer continues. “No, there is no other”. But the lawyer is persistent: “Socialistic?”. The silence follows. “So, can you imagine Poland without socialism?” – asks the counsellor. “It is hard”. “Exactly”. This dialogue very accurately summarises what was going on in many Poles’ minds at the time. They appear to be a nation that enormously yearns for freedom. He desperately tries to conceive free Poland but he cannot do this yet. As the next crises ensue, among widespread unrighteousness, a feeling of hopelessness and overwhelming malaise, gradually, the first swallows – the harbingers of change – begin to appear. First, we dream about attempting escape, though we do not believe much in the success of it. Little by little, we dare dream about successful liberation. Gaining freedom outside our country seems within our grasp. Then, we go a step further: we dare dream that we could live better not in a faraway place, but here – in the place we know and hold dear.

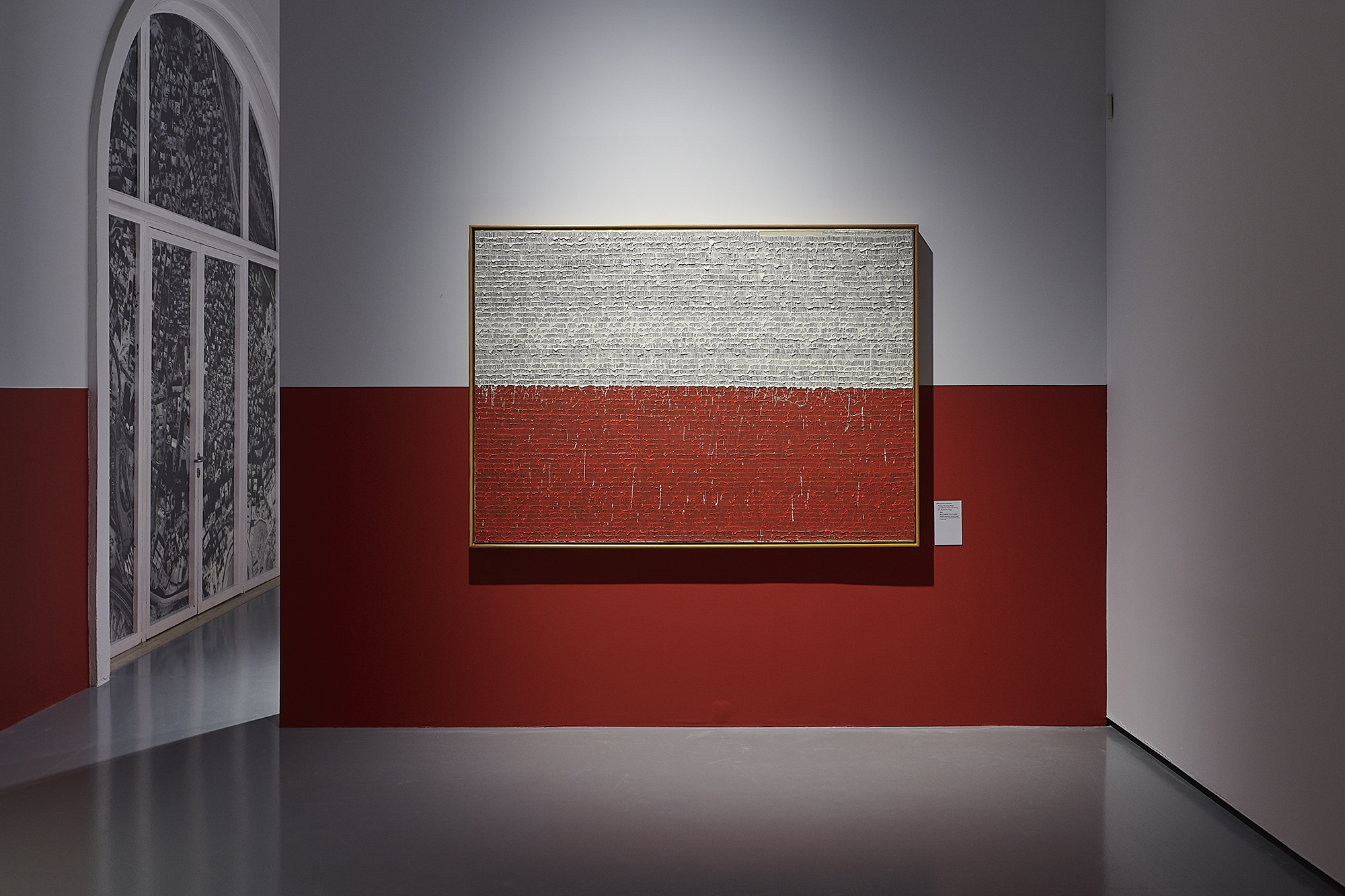

The exhibition Nie ocenzurowano at the Center for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle, photo: Adam Gut

On the face of it, “The Big Run” (1981) – a great picture by Jerzy Domaradzki – tells a story about long gone Stalinism, though much like many other films, it had to wait for its premiere until 1987 due to the fact that it accurately exposed immanent patterns of Communist system, still present at the time, though less ostentatious. And since in 1987 one was allowed to talk about this topic, maybe it was also possible to have hope. The very shift towards change is aptly portrayed in Magdalena Łazarkiewicz’s “The Last Schoolbell” (1989). The community uniting against the danger, the need to fight for things we miss as well as the price one has to pay when the fighting is done – all those themes are present in the film. There is also Jacek Wójcicki who sings in Jacek Kaczmarski’s song about a fire in a mental asylum: “And we don’t want to run away from here!”.

That is right: “we”. A community is absolutely vital for any change. To find the trust that got lost somewhere along the way and was crushed by Communist regime. To recall the idea of sacrifice so deeply rooted in our nation. The concept of solidarity. Polish society showed in the eighties cinema appears to be a community that merely starts to develop a sense of unity. It is coming to life again. Free Poland is somewhere there – under the eyelids – but when one opens their eyes, it instantly flees like the remnants of a forgotten dream. Still, it is there, deep inside, waiting for the courage to dare and crave it. To imagine it and then believe. And finally reach for it. Together.