The art of Southeast Asia has, to date, only had a limited reception in Poland. Save for the history of the Indochina wars, keen interest in the region’s cinema or a vision of searching for lost time in exotic holidays (or worse still, in confusing reality shows like Asia Express),[1] Southeast Asian art has yet to be fully appreciated. There remains work to be done in getting to know it and understanding its pluralism and great diversity.

The only, if indirect, exception from that state of affairs in recent history was a brisk cultural and economic exchange during the era of Soviet globalization. One of its results in Warsaw (but also, for example, in Wrocław) is an active, numerous and well-organized Vietnamese immigrant community. In 2009, its presence in monocultural Poland inspired the authors of the project Stadium X: A Place That Never Was to provide the first constructive, if short-lived, commentary on the “unforgetting” of various connections and intertwined histories. Artists, researchers and last, but not least, the Vietnamese immigrants themselves began attracting public interest in Warsaw,[2] which however quickly lost traction when the Jarmark Europa open-air market was restored to its previous sports function as the National Stadium, resulting in the Asian stallholders’ relocation to the suburbs. In the meantime, before and after Stadium X, valuable exhibition projects of various scale have been carried out, such as the Zachęta National Gallery of Art’s or the Museum of Modern Art’s surveys of the global South or the recent exchange between the Art Academy of Szczecin and the Bangkok Art & Culture Centre (BCC). None of those, however, engaged in broader dialogue with the Southeast Asian art world.

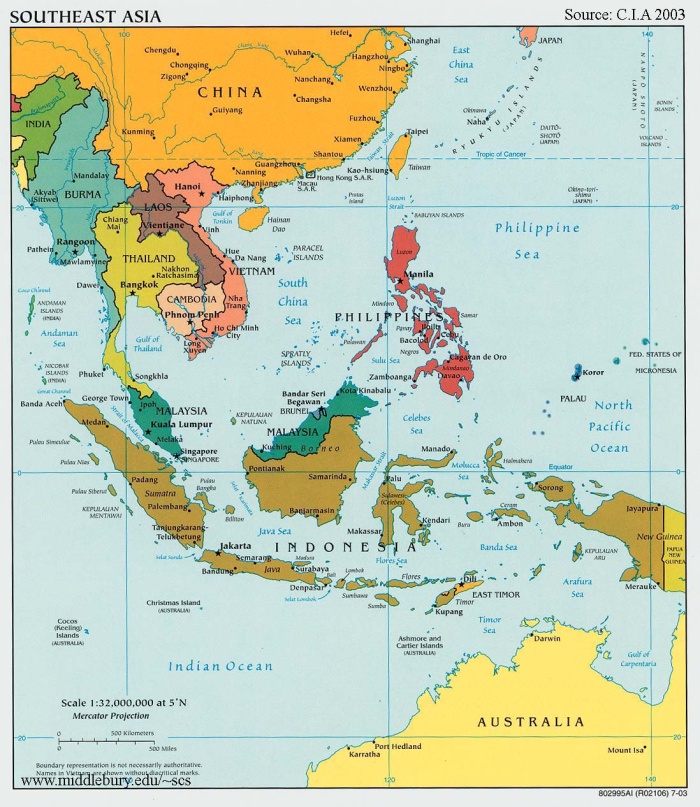

In response to questions raised by the exhibition Spirits of Community at the CCA Ujazdowski Castle, we propose a wider exploration of artistic issues and identities, starting with the island state of Taiwan, through Vietnam, Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, to the city-state of Singapore. All these places have seen the phenomenon of the emergence of Southeast Asian contemporary art “worlds,” increasingly including the region, from the dawn of the globalization era (that began with Japan’s economic boom in the 1980s), in the global art circuit, through growing “biennalisation,” to more recent concepts of “critical regionalism.” The suggested map is of course but an outline of a complex cluster of meaning that we are keen to elaborate on in this and successive issues of Obieg.

The relative non-visibility of Southeast Asian art stems to a certain extent from a sense of discomfort caused by its diversity and multiplicity, which many commentators tend to minimize under the umbrella term of “Asian art.”

The wealth and diversity of Southeast Asian art and the complex relations between the different countries reflect both the limitations of the nation-state model and difficulties in the region’s recognition by the global art scene. In this latter aspect as well, the art of Southeast Asia seems opaque from the perspective of Europe’s dominant models of contemporary art. Models that are pluralistic and open vis-à-vis selected fragments, but somewhat closed where broader analysis, comparisons or clarity of interpretation are concerned. The relative non-visibility of Southeast Asian art stems to a certain extent from a sense of discomfort caused by its diversity and multiplicity, which many commentators tend to minimize under the umbrella term of “Asian art.” Therefore, taking a closer look at Southeast Asian art, we broaden the discussion, started with the issue no. 1 of the new Obieg, of “parallel contemporaries,” a term harking back to one of the first online anthologies of this art, Comparative Contemporaries. This parallel contemporaneity may be not just modernity here, as suggested by Terry Smith,[3] but perhaps an apotheosis of what a matured, or developed, Western modernity sought to achieve.

Obieg no. 2 offers a slightly different formula than before, both because materials will be published successively and through its multifaceted exploration of a larger region. On the whole, it is a review of various ways of presenting and describing “non-Western” art in a local, regional and global artistic context. It seeks to capture how the authors and artists cited are searching for new meanings for Benedict Anderson’s notion of “imagined communities,” and highlights the ironic and “creative” attitude of the region’s art in the face of a post-traumatic reality. Maintaining a critical distance to local traditions, the shadows of the recent past and the luxury of global contemporary art, the featured authors ask about how the different Asian identities – Indonesian, Malaysian, Philippine, Singaporean, Southeastern Asian – have been engaged in the development of the region’s artistic practices since their “explosion” in the 1990s.

This playful, humorous – and often subversive – approach of Southeast Asian art to the region’s traumatic crises can inspire us to reflect on the dwindling of community spirit and growing pessimism in Europe. The art or artistic practices of Southeast Asia demonstrate that future outcomes shouldn’t necessarily be sought in the past. Instead of listening to history or historical narratives, they urge us to listen to, and interact with, each other.

Mapa Azji Południowo-Wschodniej wg CIA, 2003. Źródło: wikicommons.

In this issue of the new Obieg we trace connections between seemingly distant localities. The opening essay, by Weng Choy Lee, the initiator of Comparative Contemporaries, a pioneering web platform bringing together art writing from across Asia, deals with Singapore and the changing condition of art criticism in the region. Malaysia-based contemporary art researcher, Simon Soon, presents a brilliant outline of critical regionalism in the context of the globalized role of curatorial practices; while Iola Lenzi, a critic and art historian active between Singapore and Hong Kong, introduces us to the vernacular aspects of playfulness and performativity in Southeast Asian art. Several other essays – by Patrick D. Flores (Philippine art historian and curator), Ron Hanson (co-editor of the Taiwanese independent magazine White Fungus), Thanavi Chotpradit (researcher from Thailand), and Nora A. Taylor (who specializes in Vietnamese contemporary art) – analyze selected themes connected with notions of social critique and engaged art. Some of the subjects tackled include affective labor undertaken by Philippine immigrants, Yao Jui-chung’s subversive practices in Taipei, the geopolitical aesthetics of Thai public memorials, or Vietnamese artists subversive playing with a traumatic past. Rounding out this collection of texts is a larger essay by David Teh (Singapore), exploring interdependencies between global art and critical regionalism in the context of the Asian biennales.

We’ll soon be adding essays on techno-Oriental aesthetics by Francesca Girelli (Shanghai), while Pandit Chanrochanakit (Thailand) will be exploring Thai artists' practice on “political art” or how they contribute to Thailand’s political crisis from 2010-2016. We will include two conversations, from Monica Narula (India) about her curatorial project of the 11th Shanghai Biennale, and about the condition of art institutions in the region with Kwok Kian Chow (Singapore), among others. We’ll also be introducing the White Fungus magazine (Taiwan) and posting audiovisual materials.

I would hereby like to thank all the authors. Special thanks are due to Weng Choy Lee, Kwok Kian Chow, Ute Meta Bauer, and Thongchai Winichakul for their valuable suggestions and help in making this issue happen.

Translated from the Polish by Marcin Wawrzyńczak

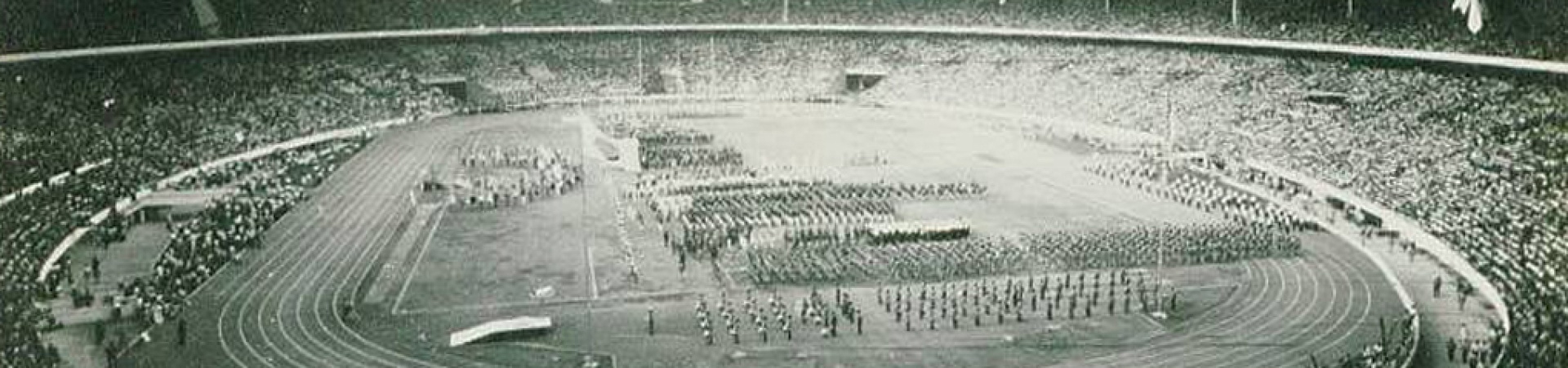

*Cover photo: Opening of GANEFO (Games of the New Emerging Forces), Jakarta 1963. Source: wikicommons.

[1] A TVN reality show, aired in autumn 2016, that reeked of the colonial and the sly. Polish celebs travel around Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and Thailand. In selected cities, they must get from A to B on a budget of $1 a day.

[2] Cf. Stadion X – Miejsce którego nie było, ed. Joanna Warsza, (Kraków: Ha!art, 2008).

[3] Terry Smith, “Contemporary Art and Contemporaneity,” Critical Inquiry 32 (summer 2006), p. 686.