Ukrainian president Zelenskyy’s war speeches are unlike any other speeches given by any of contemporary politicians. They are not concealed in veil of false diplomacy. When there is war, there is no time for such diplomatic screeds. Words need to be accurate, similarly to evangelical yes, yes; no, no. Murders must be called murders and every freedom fighter has to be inspired to defend independence.

On the eighth day of the invasion, president Zelenskyy spoke the following upon appealing to countries of NATO:

If we are gone, the next country will be Estonia, then Latvia and Lithuania. After that Georgia, Poland.

These are words similar to ones we have heard before. Fourteen years ago in Tiblisi, to which Russian tanks were approaching dangerously close, Polish president, Lech Kaczyński, said:

[…] today it is Georgia, tomorrow it is Ukraine, the day after tomorrow time will come for Baltic countries and then, maybe, for my country, for Poland.

How unsettlingly predictive these words have become.

In 2010, Lech Kaczyński died as a result of an airplane crash in Smolensk. Along with his wife, Polish generals, parliamentarians and other members of official delegation commemorating Polish officers murdered by Soviets in Katyn. To this day, we do not know what caused that airplane to crash. Russians did not return the wreckage of the plane and the area where it fell was quickly utilised. No monument was placed there that would have been a sign of decretive friendship confirming Donald Tusk’s and Vladimir Putin’s new turn in Polish-Russian relationship. Black, basaltic tiles that were supposed to be used for the road alongside the line of touchdown zone, where unfortunate airplane was to land, are now stockpiled next to a fence in the Centre of Polish Sculpture in Orońsko. In fact, these piles are more telling than a complete monument; provided it was one day finished, that is. It is a reaching hand of victim’s descendants ignored by descendants of executioners.

Those crumbling pieces of monument in memory of Smolensk disaster’s victims, that was to stand near Smolensk-Severny aerodrome, are a suitable commentary on Polish artists’ approach on the subject. The world of Polish art simply “moved on” in reaction to this event. A few artists who decided to raise the subject were deemed politically incorrect: Russophobe, lunatics, members of Smolensk sect. The very will to memorialise Smolensk’s air disaster victims in art was met with taunts. For those few artistic signs of commemoration, mainstream media coined a phrase “Smolensk art”. In their opinion, it was synonymous of cliché and bad taste, as if a mere take on this subject had to result in production of artistically poor piece. Meanwhile, among just a few pieces of art created, one could find those which were given credit – though not openly – also by the left-wing critics’ side.

Jacek Adamas, Artforum, 2011

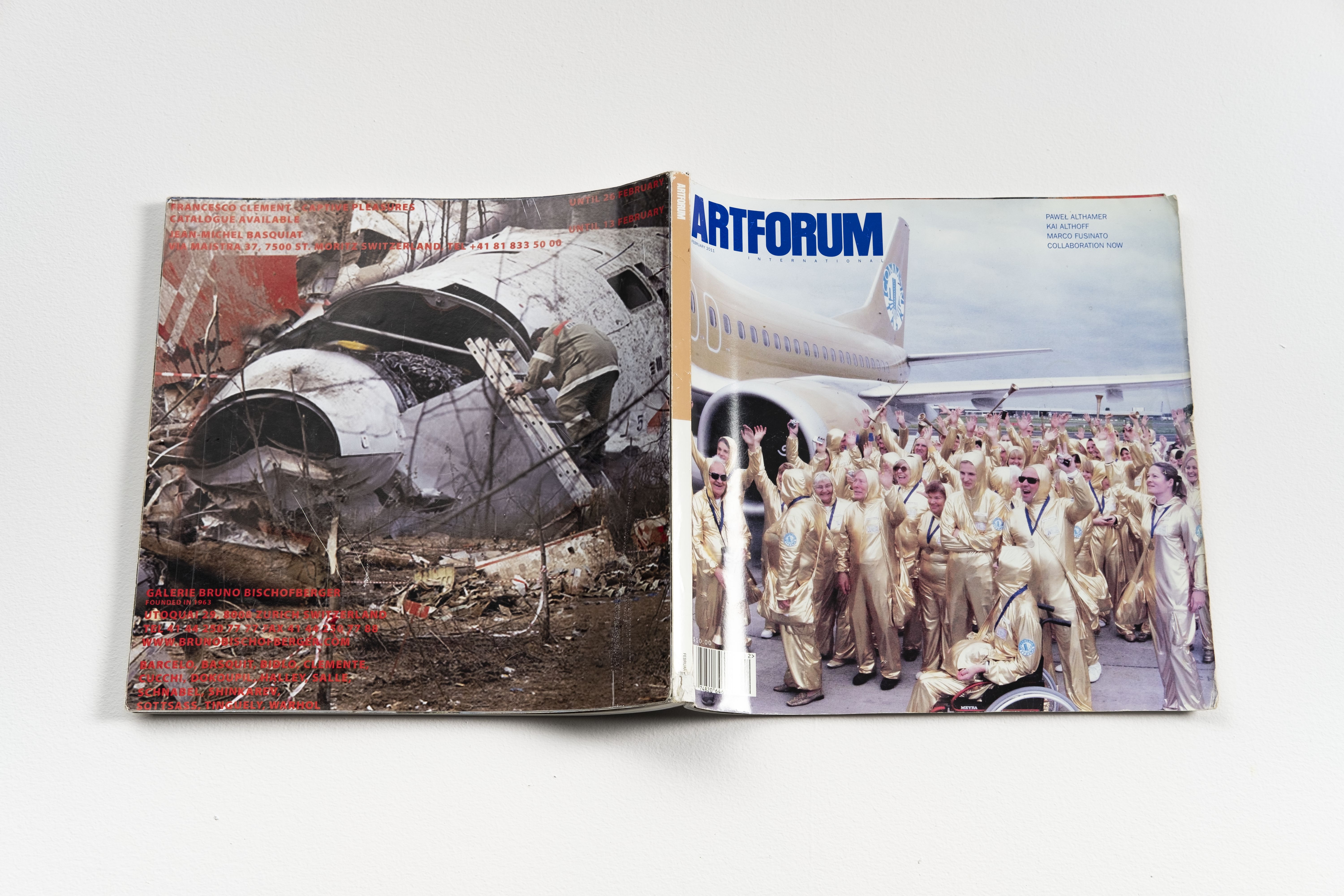

One such piece is „Artforum” by Jacek Adamas which has been a part of Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art collection since 2020. The work presents an issue of Artformum magazine from February, 2011. The paper is open, as if it had fallen to the ground with its cover up. Two distinctive photos can be seen on the magazine’s front cover. First, authentic photo taken from this issue shows a plane painted gold and men in golden suits. It is a documentary on action performed by Polish artist, Paweł Althamer, in June 2009, on 20th anniversary of partly free elections due to which Solidarity Movement established first non-Communistic government with Wojciech Jaruzelski, past dictator and martial law author, becoming president. In memory of this anniversary, Paweł Althamer decided to costume his family, neighbours, journalists in gold suits and then, he asked the whole group to board the plane, chartered for this special occasion and also painted gold, which flew straight to Brussels. Golden people took a walk around the capital of European Union and came back to Warsaw. The action attracted huge public attention, outside Poland as well. It was a testament to successful transformation, facilitating the change from communistic countries on the verge of bankruptcy to full European Union membership. The gold colour equalised all lights and shadows under one, unambiguous and sugar-coat optimism – an important part of anniversaries – with the photograph taken during the event making its way to the cover of the well-known international art magazine Artforum in February, 2011.

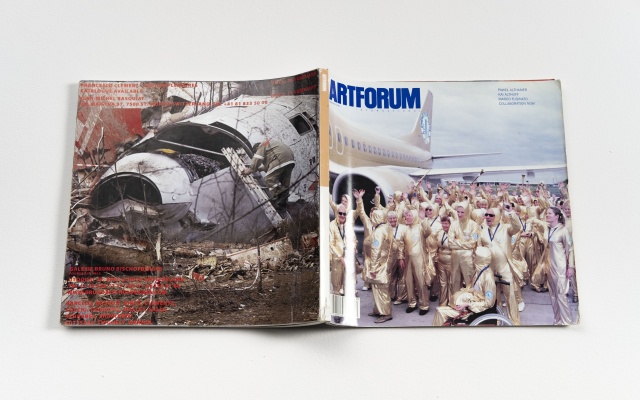

In his work, Jacek Adamas juxtapose the photo from the event with a photo of a different plane which became famous in Polish media merely a year after Althamer’s action – a fragment of president’s airplane that crashed near Smolensk. Though it is a record of a different journey, different delegation, with a completely different destination – the photographs are placed in such a way that the golden plane and a part of the wreckage appear to form combined entity, as if they were part of one and the same aircraft. A simple gesture made in the face of a tragic event resembles tearing down false golden foil, not as shiny as one would seem. It is an action of an artist who, in defiance of Midas, does not desire to change everything he touches into gold but it is an artist, who wishes to touch reality, touch the truth with his art.

In fact, Adamas’ work is the very essence of political art. However it was not exhibited at “Political Art” exposition, prepared by Jonen Eirik Lundberg together with me. In retrospect, I find that course of action a huge mistake. “Artforum” would greatly harmonise with Waldemart Klyuzko’s “Shattered Plain” installation about Malaysian airlines plane shot down by Putin’s men in 2014 in the Ukraine’s airspace or Wojciech Korkuć’s poster “Achtung Russia” warning against imperialistic designs of Putin’s after annexation of Crimea in 2014 or, last but not least, Aleś Pushkin’s “The Picture of Freedom” telling the story of how freedom was suppressed in Belarus by Putin’s ally – Lukaszenko. This absence was pointed out by Adam Mazur in his review of the exhibition published in Frieze magazine. He perceives Adamas’ work in a broader context, as a symbol of change in Polish art in recent years:

The current situation in the Polish art world (…) is well illustrated by Jacek Adamas’s 2011 work, Artforum. Having recently been acquired by Warsaw’s Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art (UCCCA) – one of the most important public collections in Poland – the piece has once again become the subject of debate, a decade after it was first shown. The work comprises a copy of the February 2011 issue of the well-known US art magazine laid out so that both front and back covers are visible. The obverse features a photo of the ‘golden aeroplane’ that sculptor Paweł Althamer and his collaborators took to Brussels in 2009 as part of Common Task – a project celebrating the 20th anniversary of the fall of communism in Poland. The reverse shows the wreckage of the Polish presidential plane after it crashed near Smolensk in 2010, killing 96 people, including then-president Lech Kaczyński. To nationalists, the crash is a symbol of Poland’s collapse into an ineffectual, depraved state subordinated to Brussels, at the mercy of Germany and Russia. The radical right believes that the crash was an assassination orchestrated by Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Is that so? Are nationalists and extreme right had such a clarity of vision to see what is now obvious for everyone living in Europe? Pointing out that Putin is a criminal capable of anything and German cooperation with other countries of Western Europe drove the war machinery, ignorant of warnings coming from countries like Poland? That yesterday it was Georgia, today it is Ukraine and next is Poland? No, the terms used – nationalists and extreme right – are pejorative epithets deprecating in the eyes of public opinion those, who simply looked deeper, under the foil of dominant phraseology produced as a smoke screen for business cooperation with unpredictable dictator. It is exactly how Putin justifies his invasion of Ukraine: with a will to liberate Ukrainian nation from the reign of mysterious nationalists.

Alas, Adamas’ work is still valid up to this day. One cannot deny Mazur’s point, who wrote his text yesterday, as though holding onto belief shared by the rest of Europe, that Russia is a regular business partner, though a bit exotic at times. The reality seemed to have caught up with the vision presented by the artist. Or maybe, it is just that this reality, unseen by many other artists who similarly to politicians tried to cover their art in foil of ideologies detached from reality, rendered their work obsolete?

In president Zelenskyy’s words today, Kaczyński’s words from the past echo. Tomorrow is today – Ukraine is in flames after Putin’s barbaric attack. What is going to happen the day after tomorrow? In the aftermath of this attack, will art claiming its right to educate and shape societies resort to false gold masking reality once more?