Firoozeh Bazrafkan argues that suppressing the Muhammad cartoons in history books will accelerate the decline of freedom of expression.

In a Berlingske (Danish newspaper) debate article from February 6, law professor Ditlev Tamm argues that Muhammad cartoons should not be included in Danish history canon or primary schools. His advocacy, however, seems to be a poor excuse for not saying what the issue is really about.

Tamm does not believe that the Muhammad crisis in the years 2005-2006 should be part of the Danish history canon. He does not explain why, so we can only quess. In addition, he says, we must understand that the problem surrounding the cartoons is complex and requires considerable analysis. He goes on to say that pictures of the cartoons are not necessary to discuss the Muhammad crisis in school, and that a teacher should only discuss the crisis in school if it is absolutely necessary for him or her to do so.

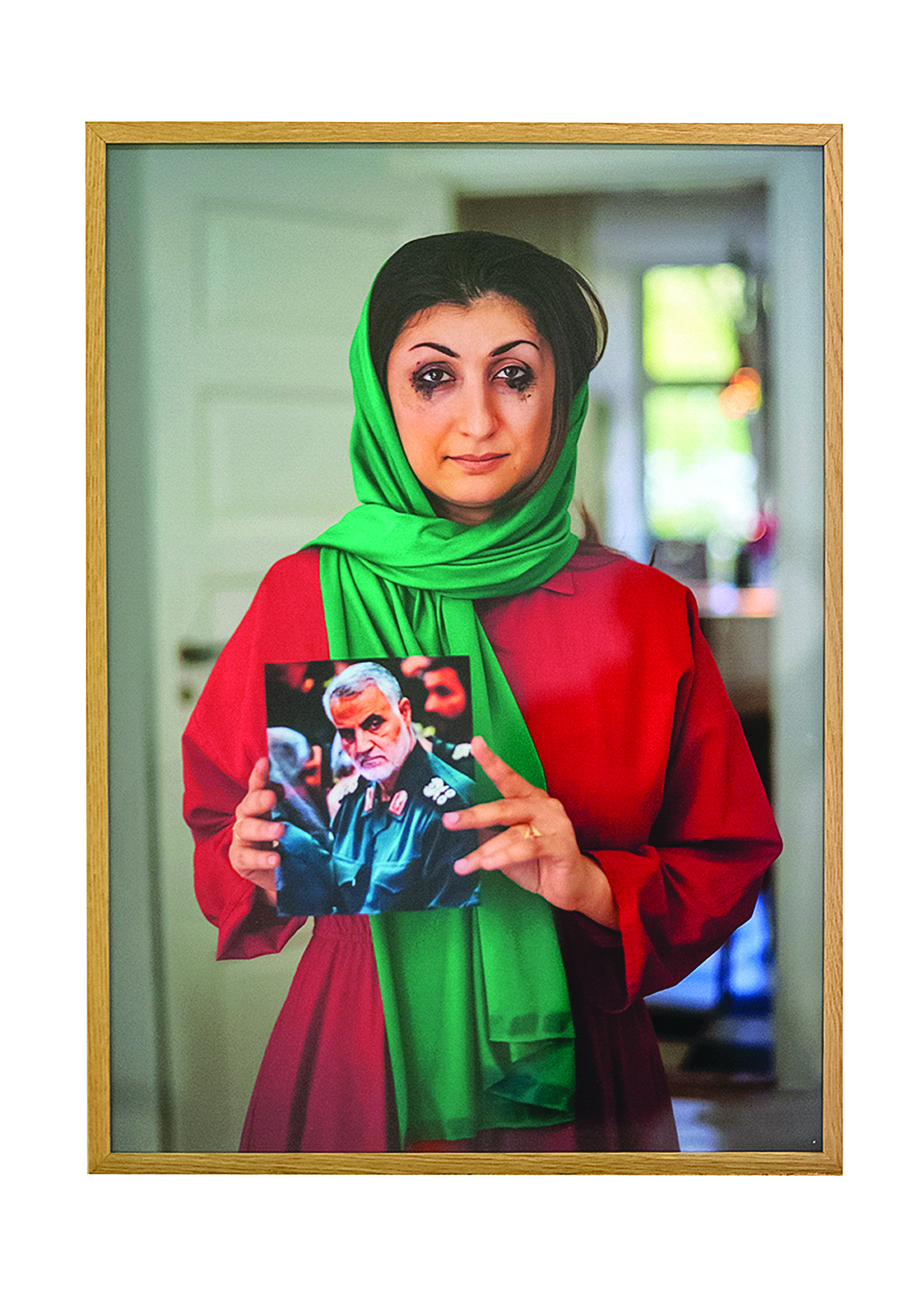

Firoozeh Bazrafkan, Political Art Exibit

It is absurd to think that not displaying and teaching the cartoons of the Muslim prophet is irrelevant. In fact, this is the worst foreign policy crisis for Denmark since World War II> TO teach without showing the cartoons would be as absurd as not telling about them at all. To do so would be akin to teaching the story of Danish artist Wilhelm Freddie’s imprisonment without showing the work of art that led to his conviction. It is unlikely that students would be able to appreciate the complexity of 1930s views on art and pornography if they were not permitted to see Freddie’s ‘Sex Paralysis Appeal’.

Understanding some things requires you to see them. The Egyptian newspaper al-Fajr also expressed this opinion when it published the cartoons in the autumn of 2005. Readers would then be able to understand the point. Muhammad is also displayed by the clerical regime in Iran. Not with the cartoons from Jyllands-Posten (Danish newspaper), but with street corner drawings produced by the Iranian regime itself.

Firoozeh Bazrafkan, Woman, 2021

The only reason not to show the drawings is fear of violence and threats. However, we only handle it by adding the Muhammad crisis as point 30 to the Danish history canon. By putting the topic in the history canon, we secure that no teacher is left alone with the task when students ask questions. We all share this public task.

Freedom of expression includes the right to show and draw the prophet Muhammad. And freedom of expression is not complicated at all. It mainly protects minorities. Minorities will be unable to express themselves on topics that may be more significant than satire caroons if freedom of expression is denied. By supressing the Muhammad crisis in our history books, we are advancing towards the decline of freedom of expression.

So dear Ditlev Tamm, why all this talk when you may truly be scared? Maybe not for yourself, but probably for others. Do not ask the teacher to stare at the floor when students ask why they are not allowed to see the Muhammad cartoons. Do not leave the teacher alone if he or she decides to display cartoons. Do not deny any Danish school student the opportunity to learn about the history of their country.

Cartoons of the prophet Muhammad should not be taboo. Myths are created by taboos.

Our history cannot be changed. You have to live with that.

Firoozeh Bazrafkan is a performance artist. Her article appeared as "Gør ikke Muhammedtegningerne til taboo, Ditlev Tamm" in Berlingske magazine on February 8, 2022.