Deformed Thai Politics 1

At a Brooklyn talk, a public event hold by the Brooklyn Museum, Ai Wei Wei responded to Tania Bruguera’s question on how and why the political arts matter. Bruguera asked Ai what he thought about ethical issues when he took a photograph of himself as a Syrian refugee, Aylan Kurdi, whose body washed up the beach of Turkey. Ai asked her how many people died crossing the ocean from Syria. Bruguera was stunned while Ai responded: “You don’t know the number. Because you are not a full political artist. You are only a Cuban political artist.”2

Such a harsh reaction stirs the conversation on how to be a “political artist.” Even though I did not totally agree with Ai, his thought triggers a question: how far could an artist engage and contribute to political movements and be politically correct?

It has been a decade since Thailand fell into a series of political crises: two successful coups in 2006 and 2014, political violence, before ending up with an authoritarian regime since 2014. The 22 May 2014 coup was a result of the long protest of the People’s Democratic Reform Committee (PDRC) that intended to uproot Yingluck Shinawatra’s government by closing down the streets of Bangkok, shutting down governmental offices including blocking people from voting in the February 2014 general election.3 The PDRC condemned the majority of Thai voters in provincial areas as being poor and uneducated so that their votes could be bought by bad politicians. They also believed that the 2014 general election could only uphold the power of the Yingluck government.4 At the same time, the PDRC called for an unelected government, appointed by the King, which is both unconstitutional and undemocratic. In many ways, their actions led to the army intervention. As a result, Thailand has since lost it democratic regime.

The PDRC supporters overlook the fact that Suthep Thueksuban, a leader of PDRC, was formerly Deputy Prime Minister to the Abhisit Vejjajiva Government, who deployed the army to crackdown on the United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship (UDD) protest camp, in the heart of Bangkok, from 10 April – 19 May, 2010. As a result, more than 100 died and almost 2,000 were injured. The Thai courts ruled that it was relevant that the Thai army officials fired at civilians. While many UDD protesters are jailed and sentenced for violations of the law, Suthep, his cabinet members, and army leaders are free, leaving the fact that not only were UDD protesters killed and jailed, but they were also only ordinary people who had nothing to do with political motivation.

After months of camping and blocking the streets and government offices, the PDRC failed to take over state power even though Suthep kept announcing the last move to maneuver and make the state sovereign. After Yingluck stepped down and called for general election on 2 February 2014, they advanced further by blocking election booths and preventing people from voting. Even though they seized some polling stations, more than half of the voters were able to exercise their right to vote and more than half of national polling stations were open. However, the 22 May 2014 coup further disrupted solution.

One of the most important relations between the PDRC and Thai artists is that Thai artists joined PDRC and organized Art Lane, a network of artists, designers, and cultural workers, to raise fund for them. Some tried to deny their connection to the PDRC but the witnesses and facts are evident. Besides, after the coup they have remained silent about protection of democracy, fighting against corruption, and human rights. This article explores the relationship between artists and their works, and deformed Thai politics.

Art without Avant-Garde

Vasan Sitthiket is a performance artist, printmaker, anti-war activist, musician, writer, and poet. He has worked on the theme of politics, in which it is considered obscene, offensive, and dangerous. For example, his exhibition Inferno (1991) appropriates punishment according to the Buddhist’s notion of hell into modern acts. In a piece The Punishment of Those Corrupted Politicians Whose Flesh Would be Cut in Pieces, Being Fried and Fed him Until His Death, Vasan depicts a politician whose body was dissected and fed to him until his death. He uses bold colors and simple lines to draw on the horror of modern sins that could only be redeemed in hell.

In a series of shadow plays, Truth Is Elsewhere (2004) Vasan creates 50 leather puppets characterized after famous politicians who have contributed to atrocities. Vasan uses the puppets to tell the stories of corrupted politician.

In a shadow play “Money Has No Color,” He narrates:

“It’s better not to be living,

If there is no democracy,

Why should we go on living,

If we have no freedom?” 5

Vasan founded a pseudo-party, the Puer Koo Party (the For Me Party) in 2001, in order to establish an anti-capitalist party including the Thai Rak Thai Party under the leadership of Thaksin Shinawatra. However, the making of a political party at that time was just a pilot project for the Artist Party.

During the 2005 general election, Vasan Sitthiket launched his Artist Party aimed at promoting decentralization, getting rid of the mafia, seizing assets of corrupted politicians, and self-governing. The Artist Party had a slogan “The gist is non-governing.” Vasan is an active and socially-engaged artist who does not hesitate to join under-privileged groups of people to criticize any government. He engages with environmental activists and movements. His works focuses on criticizing and condemning exploitation of the poor and of exposing corrupted politicians; he also criticizes American imperialism.

Founding the Artist Party, he claimed that it would be a wake-up call for “a real political reform.” Vasan says, “My intention is not to attack any specific political party. Anti-capitalism or anti-globalization is not communism or Marxism, but it is about revolution.”6

For Vasan, “democracy has been made to serve only some politicians and a small elite group. He argues that “it’s like we are living in a fake ‘demon-crazy’ world, in which the ‘elected representatives of people’ are the real power-holders behind an illusion of democracy. As a result, there is no more government for the people, by the people, and for the people, but rather a government of capitalists, by capitalists, and for capitalists.”7

Even though the Artist Party is just a mock party, not officially registered for the 2005 election, its posters and his leaflets were widely displayed and distributed. The active members of the Artist Party are Jumpol Apisook, Jantawipa Apisook, Chuang Moolpinit, Naowarat Pongpaiboon, including an active and critical thinker Sulak Siwaraksa, and a son of the late Prime Minister Chatchai Choonhawan.8

One example of Thai political art is a group exhibition History & Memory (2001) by Sutee Kunavichayanont, Manit Srivanichpoom, and Ink K. In “History Class” (2001) Sutee engraves words and pictures from modern Thai political history on the top of 14 school desks. Each desk contains a story and scene from modern Thai politics. Some of these stories were even excluded from text books. The audience can copy these alternative Thai historical scenes by laying a piece of paper on the top of the engraved desks and rubbing on them with a soft pencil. The 14 desks were first exhibited in front of Democracy Monument both creating a challenging juxtaposition and fulfilling national history.

At the exhibition hall, Sutee put the 14 desks in front of blackboards depicting a classroom-style. On the blackboards were traces of the written history of modern Thai politics, some still clearly legible, some already cleaned up.

Sharing the idea of hidden history, Manit Sriwanichpoom, entitled his work Horror in Pink, in which he edits photos from the 14 October 1973 uprising and 6 October 1976 massacre, by putting a man in a pinky suit observing, intervening, pushing a shopping cart through Thai violent scenes without seemingly caring. The pink man represents Thai people’s ignorance of the history of violence in Thai society.

In the same group exhibition, Ink K. painted portraits of King Mongkut, King Chulalongkorn, Pridi Bhanomyong, and her granny. All those depicted are crying. The tears of her subjects convey the sad and hidden stories of Thailand’s national history.

Vasan and the three artists stage Thai political history as non-linear, obscured, and discontinued. They highlight experiences that could not be said in daily life. Such an approach is quite advanced if considering from the aspect of contemporary art.

Relational Aesthetics Ends Here

“Actually, there is currently a huge show called Imagined Peace at the Bangkok Art and Cultural Center. They claim that the aim is to heal our society through art, after the recent political conflict that erupted in unexpected violence and bloodshed on the streets of our country. Although I like a few pieces in that exhibition, including your powerful drawing, it is sad to see that artists are being used as tools for government propaganda.”9

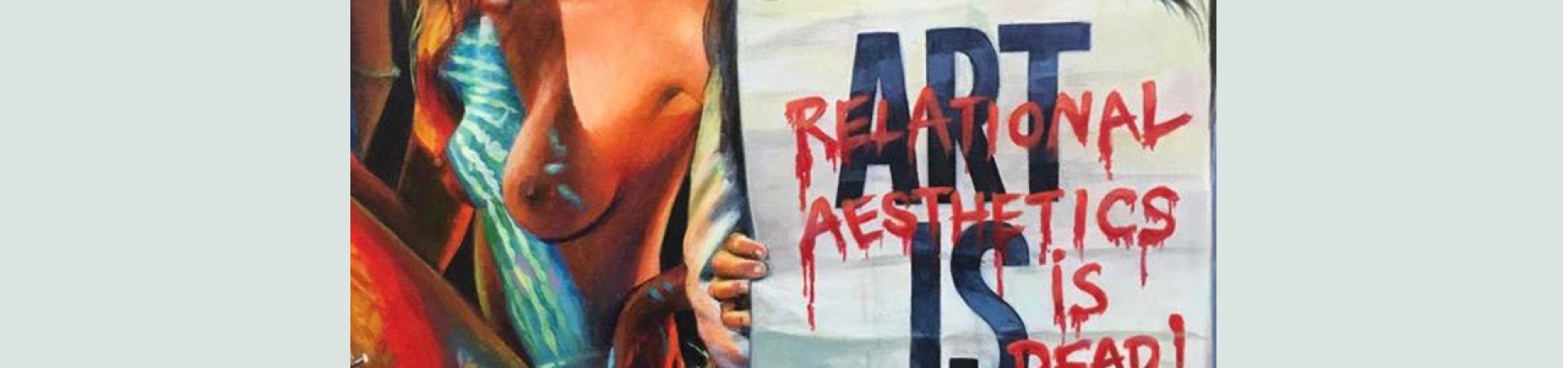

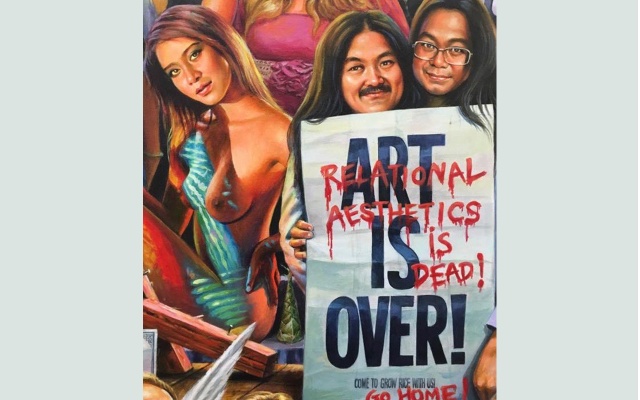

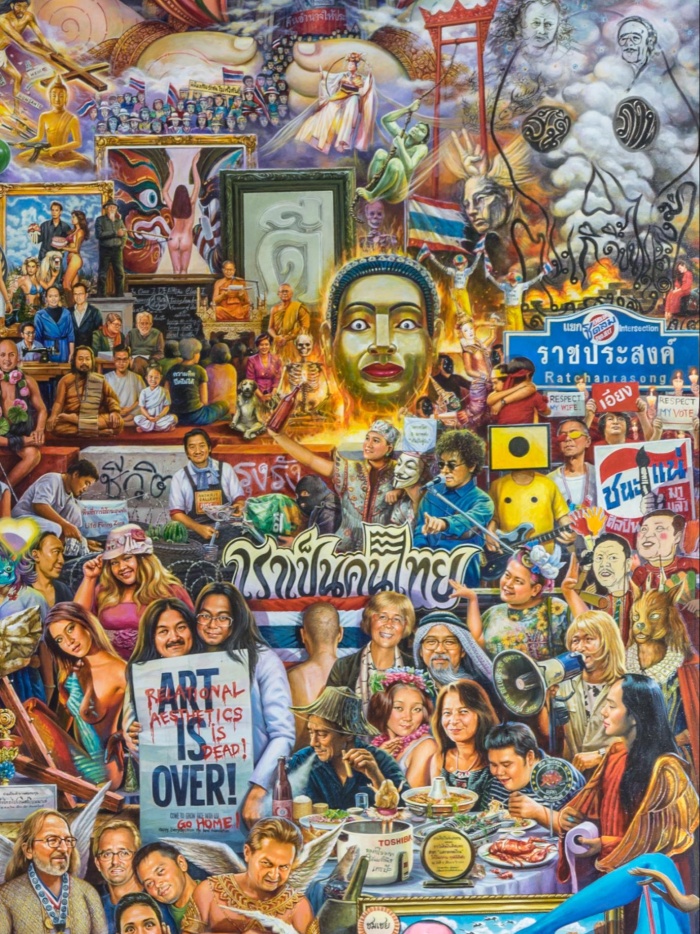

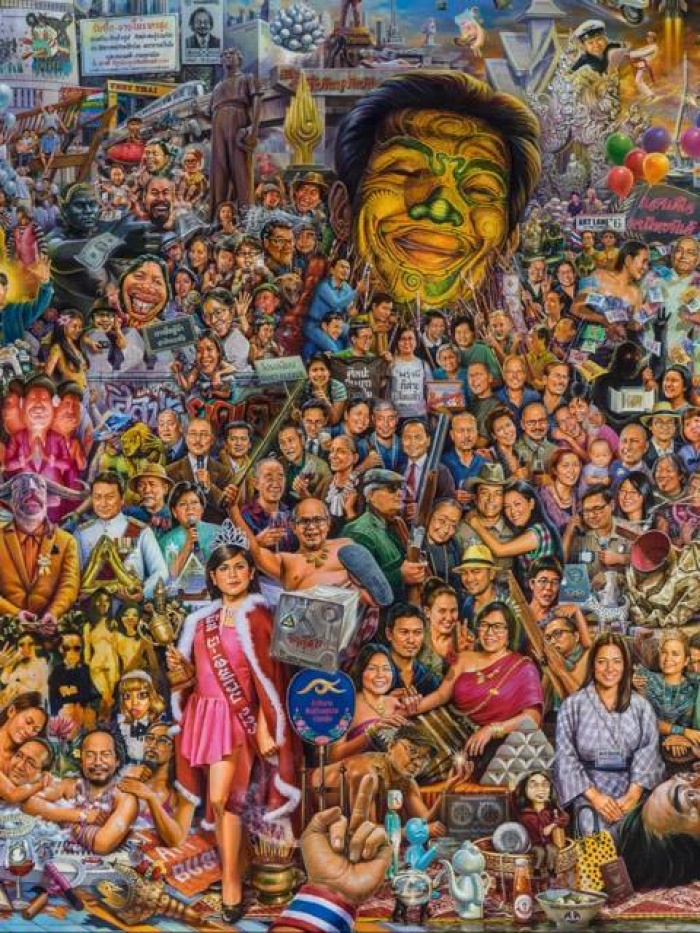

Il.1 Navin Rawanchaikul, Super (M)art, 2014–2015. Kolekcja Maiiam Contemporary Art Museum, Chiang Mai, Tajlandia. Dzięki uprzejmości Navina Rawanchaikula. Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone.

In his Super (M)art (2015-2016) at Mai Iam, a privately run contemporary art museum, Navin Rawanchaikul portrays people from the Thai and international art scene. His painting contains not only art, but is also a Thai political record. One of the highlighted works focuses on Rirkrit Tiravanija being impersonated and Kamin Lertchaiprasert holding a sign that reads “Art is Over!” but there is a hand written red paint sign that reads, “Relational Aesthetics is Dead!” and “Go Home!”

Behind the sign “Ratchaprasong” (intersection) is Peace will happen we must kill…greedy angry elusion in ourselves first (2010), a work by Kamin made for the exhibition Imagine Peace (2010) curated by Apinan Poshyananonda right after the 2010 crackdown on Red Shirt protesters. Navin depicts Suthep Thueksuban (aka Loong Kamnan) the supreme PDRC leader, during his monkhood in the middle of a fire, next to Ravinder Reddy’s head sculpture that was installed in front of the Central World Department Store. These components narrate and question the fact whether Suthep, the Deputy Prime Minister, was responsible for the 2010 crackdown that caused the death of 100 people and injured a further 2000. And yet Suthep led the PDRC to overthrow an elected Yingluck Shinawatra government. The story centered on Ratchaprasong Intersection, the heart of the UDD protest site, and represents the support of artists for Abhisit Jejjajiva and Suthep Thueksuban’s administration. Besides, Mom Rajawongse Sukhumpan Boripatra, the then Governor of Bangkok Metropolitan Authority and a member of the Democrat Party, organized a “Bangkok Big Cleaning Day,” supported by some young artists, to clean up the area, and wash away the scenes of bloodshed at the intersection. Krungthep or Bangkok, the City of Angels, thus became ‘clean and neat’ again ready once more for a heavenly shopping experience.

Imagine Peace (2010) was intended to “[H]eal Thai people’s spirit, promoting peace and reconciliation, and revive the image of Thailand,” according to Nipit Intrasasombat the Minister of Culture.10 More than 100 Thai artists joined the exhibition including Tiravanija and Kamin. Tiravanija curated a section inviting young artists to collaborate in a barricade made of cactus instead of the Redshirt’s bamboo spears and barricades, thus creating a living organism.11

Tiravanija also launched the acclaimed first solo show in Thailand at 100 Tonson.12 The exhibition Who is Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Green (2010) not only highlights the past political violence in Thailand but also the on-going political crisis. The project was inspired by a series of Barnett Newman’s work titled “Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue (1966-1970).” Tiravanija composed mural scenes from Thai political violence in 1973, 1972, and 1992. The mural put the violent scenes as inseparable from each other. Tiravanija also invited famous political figures to party in front of the scenes. To feed the guests, he cooked Thai red curry, yellow curry, and green curry for the guests. The exhibition was meant to reconcile Thais, showing that despite recent political conflict, Thais could share rice and curry from the same bowl. Tiravanija claims that it is possible to create a tolerant community.13 Unfortunately, the dead and victims of the May 2010 crackdown could not join such a warm and cheerful reconciliation party!

Tiravanija is widely known as an exemplar of the Relational Aesthetics artists praised by Nicolas Bourriaud.14 Relational Aesthetics stages art as a state of encounter that expects a complimentary situation, in which each side fulfils one another and realizes the unexpected outcome. Tiravanija’s practice has failed to include non-Democrat party supporters, not to mention the fact that many UDD supporters were jailed, injured, sent back upcountry, and are regularly visited by army officials.

Imagine Peace, a state sponsored exhibition, is a part of cultural governance projects. Thai authorities have tried to regulate, control and promote contemporary art as they realize that contemporary art is dangerous. The most satirical statement was made by David Teh, he argues “at this moment, we are witnessing the fallacy of establishing contemporary Thai art that emerged in the1960s, prospered in the 1970s and collapsed in the 1980s. It could be said that no Thai artists have escaped from their responsibility for the decaying of art’s independency from the state.”15

The sign “Art is Over!” on Navin’s painting concludes that Tiravanija’s fame as a relational aesthetics artist and as an avant-garde has ended.

A Country without Politics

Since the 2014 military intervention, Thai artists have not shown any resistance regarding human rights violations, the imbalanced use of natural resources, undemocratic practices in decision-making, and the rise corruption cases. Perhaps, their participation with the PDRC was just an excuse to get rid of those they hate – Thaksin Shinawatra and his nominees. Their act of silence could be seen as negative support and a collaborator with the junta, however.

Il. 2 Vasan przed Pomnikiem Demokracji przypomina o Dniu Blokady Bangkoku przez PDRC. Źródło: profil facebookowy Vasana Sitthiketa (dostęp: 6.10.2016).

Vasan is one of the most active artists supporting the PDRC. He poses in a picture on his Facebook wall showing himself with a painting, marking his participation in the PDRC’s Shutdown/Occupy Bangkok Campaign on 13 January 2014.

Il. 3 Sutee pracuje nad obrazem „Poo Daeng [Czerwony krab] (2013)”.

Sutee joined Art Lane, a network of artists, designers, and cultural workers, as a part of PDRC find-raising project. He painted a gigantic red crab representing Yingluck Shinawatra (her nickname being “Poo” in Thai, which translates in English to “Crab”) as a leaders of the Red Shirt (UDD supporters). On the red crab he portrayed the face of Thaksin Shinawatra the ousted Prime Minister after the 2006 coup (Figure 3). Sutee created an art activity titled Burden of Thai Artist on 2 December 2013, in which an audience posed a sign in the shape of red heart with texts read: Reform before Election (Figure 4). Sutee works on another project Thai Uprising, which uses stencil technique to make posters, protest signs, and t-shirts. After the coup, his works were sent to the Pacific City Club, an exclusive elite club, for an auction to support the PDRC foundation.

Il. 4 Znak promujący akcję „Jarzmo tajskiego artysty” Sutee Kunavichanonta i uczestnicy pozujący z papierowym sercem z napisem „Reforma przed wyborami” (2013). Z facebookowego profilu publicznego jednego z uczestników. Dzięki uprzejmości Pandita Chanrochanakita.

Other than Vasan and Sutee, – Amrit Chusuwan (the Dean of Faculty of Fine Arts, Silpakorn University of Thailand’s oldest art university) is the most important figure. Amrit asked Silpakorn alumnus and artists to support the PDRC and participated in the Art Lane activity. Hence, the PDRC artists could not deny their contribution to the political crisis before and after the 2014 coup in supporting the PDRC, an undemocratic movement.

Even though supporting the PDRC does not matter in Thailand, it matters at an international art exhibition. The controversial case is Sutee Kunavichayanont’s Thai Uprising (2013-2014) as a part of a group exhibition The Truth to Turn It Over (2016) at Gwangju Museum of Art (GMA). Sutee took four series of his works to show at GMA but the controversial one was the series Thai Uprising (2013-2014), in which he worked during the PDRC campaign to shutdown Bangkok that ultimately led to the 22 May 2014 coup. The Thai Uprising work uses a stencil technique.16 He cut templates and sprayed color on posters and T-shirts. The texts from the templates read as follows: “Thais should not be ignorant,” “Seize our Country Thailand Back!,” “The Picnic Rebellion,” “We will Win since the Artists Come to Our Aid, Victory of The People,” and so on. Even though the texts convey pro-democratic acts, the PDRC Shutdown Bangkok rallies were calling for military intervention—a coup d’ e’tat!

Thai Uprising was condemned as a displaced exhibition because the GMA has been expected to invite pro-democracy artists or those supporting human rights. Thus, it triggered resistance from both Thailand and Korea. The GMA received complaints and correspondences both from domestic audiences and from Thailand. The most active was a movement of so-called Cultural Activists for Democracy (CAD) of which I am a coordinator. In the end, correspondence between GMA and CAD was collected and published for the record and for the future historical reference.17

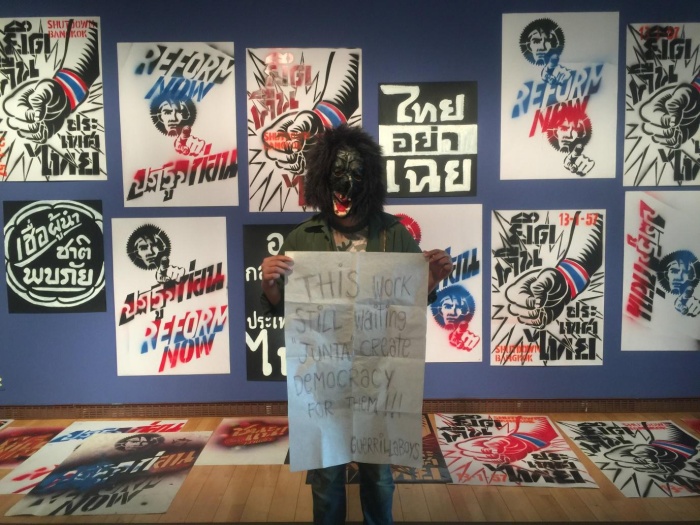

Il. 5 Guerilla Boys podczas protestu w Gwangju Museum of Art (2016). Dzięki uprzejmości Gorilla Boys. Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone.

It should be noted that during the exhibition, a member from a group calling itself the “Guerilla Boys,” wearing gorilla mask, held a sign that read: “This Work Still Waiting Junta to Create Democracy!” The act of disruption recalls what Sutee and the PDRC celebrated as “Reform before Election” and which pave the way for staging the 2014 coup. Hence, Sutee’s work and the authoritarian regime are intertwined; the history of his works with the PDRC is inevitably a march to Thai’s new authoritarian government right up to the present day.

Il. 6 Navin Rawanchaikul, Super (M)art (detal, 2014 2015). Kolekcja Muzeum Sztuki Współczesnej Maiiam, Chiang Mai, Tajlandia. Dzięki uprzejmości Navina Rawanchaikula. Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone.

In the middle of Super (M)art, Navin puts in Ai Wei Wei’s middle finger, the wrist bears a Thai flag wristband, pointing at Thai art scene. His words echo silently, “I think there is a responsibility for any artist to protect freedom of expression.”18

As far as I know, there has been no PDRC artist against the Thai authoritarian rule up until now.19

BIO

Pandit Chanrochanakit is assistant professor at the Department of Government, Faculty of Political Science, Chulalonglorn University, Bangkok, Thailand. He holds a doctoral degree in Political Science and a certificate of International Cultural Studies from the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa. His research interests focus on visual politics, contemporary Thai Art, and Thai politics and constitutions.

Other than his academic works, Pandit has been the editor of Vibhasa, a magazine on humanities, social science, and culture since 2006. He also engages with Thai art community by curating exhibitions and contributing essays to art exhibitions. Among those exhibitions, he co-curated Navin Rawanchaikul’s exhibition at Thai Pavilion for the 54th Venice Biennale 2011.

* Cover photo: details from Navin Rawanchaikul, Super (M)art (2014-2015). Collection of the Maiiam Contemporary Art Museum, Chiang Mai, Thailand. Photo courtesy of Navin Rawanchaikul, using with permission from artist, all rights reserved.

[1] This article is a part of ongoing research project ‘Constructing Perception of Thainess and the Politics of Contemporary Thai Art’ under the support of Senior Scholar Research Project under supervision of Prof. Chairat Charoensin-o-larn, Thailand Research Fund (TRF). I would like to thank Thanom Chapakdee, Thanavi Chotpradit, Thasnai Sethaseree, Yukti Mukdavijitra, Navin Rawanchaikul, and Guerilla Boys for their helps and supports.

[2] Angela Brown, “Political Reactions: A Testy Ai Wei Wei Speaks with Tania Bruguera at the Brooklyn Museum, Art News, http://www.artnews.com/2016/10/31/political-reactions-a-testy-ai-weiwei-speaks-with-tania-bruguera-at-the-brooklyn-museum/. Accessed 7 January 2017.

[3] The PDRC comprises of fractions from the Democrat Party and anti-Thaksin Shinawatra movements i.e. People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD), Santi Asoka Buddhist Sect, and so on. The PDRC believes that Samak Sundaraveja, Somchai Wongsawat, and Yingluck Shinawatra are Thaksin’s nominees. In order to clean up Thai politics, they believe that Thaksin and his supporters should be removed from offices and politics. For further detail see Pandit Chanrochanakit, “Deforming Thai Politics as Read Through Thai Contemporary Art”, Third Text, Vol.25, Issue 4 (July 2011): 419-429.

[4] I refer to Thais by their first names following the Thai custom except for Rirkrit Tiravanija whose last name is widely known.

[5] Sitthiket, Vasan, Money has No Color: A Shadow Play by Vasan Sitthiket (Bangkok: Vasan Sitthiket, 2005).

[6] Bangkok Post. 2005. “Apolitical Artist”, February 1, 2005, pp. 1-2.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Manager (Phujadkarn Raiwan). “Rue ja thueng wela ‘pak sliapin” [Or it is the era of Artist Party], January 10, 2005, pp. 33-34.

[9] An excerpt from the letter to Monti Boonma is part of Navin Rawanchaikul’s installation Please donate Your Ideas to a Silpathorn Artists in his Silpathorn award-winning exhibition held at Queen Sirikit Art Gallery from 29 July to 10 August 2010.

[10]Bangkok Art and Cultural Center, Imagine Peace, available online at http://en.bacc.or.th/event/%E0%B8%9D%E0%B8%B1%E0%B8%99%E0%B8%96%E0%B8%B6%E0%B8%87%E0%B8%AA%E0%B8%B1%E0%B8%99%E0%B8%95%E0%B8%B4%E0%B8%A0%E0%B8%B2%E0%B8%9E.html. Accessed 15 January 2017.

[11] DAWN. “Imagine Peace: Thai Exhibit on Political Crisis”, July 4, 2010. Available online at http://www.dawn.com/news/545040/imagine-peace-thai-exhibit-on-political-crisis. Accessed 5 January 2017

[12] In fact, Rirkirt’s first solo exhibition is Untitled1996 (traffic) with Navin Mobile Gallery in 1996/1997.

[13] CNN travel, “Artist Rirkrit Tiravanija tackles Thailand’s color-coded strife,” 6 August 2010, http://travel.cnn.com/bangkok/play/world-famous-artist-rirkrit-tiravanija-tackles-thailands-color-coded-strife-777837/. Accessed 5 January 2017.

[14] Nicaola Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, le presses du reel, 2002.

[15] David Teh, “Travelling without Moving” [Lae laew kwam kluenwai mai prakot], Aan Magazine [Reader Magazine], Vol. 3 issue 2 (January-March 2011): p. 155.

[16] The texts and font in Thai Uprising echoes his work Longing for Siam, Inventing Thailand (2011), in which his installation comprises of video projectors highlighting Thailand in the 1940s, plaster soldiers, and tin sheet signs. The installation recalls national history during the time of General Phibunsongkram when nationalism and militarism were promoted as official nationalism. See Sutee Kunavichanont, Longing for Siam, Inventing Thailand, 16 December 2010 – 15 January 2011, Bangkok: Number One Gallery, 2010.

[17] Gwangju Museum of Art, The Truth To Turn It Over Special Report, 36th Anniversary of the 18 May Democratization Movement Commemoration, 2016 Asian Democracy, Human Rights, Peace Exhibition, (Gwangju: Gwangju Museum of Art, 2016).

[18] An interview with BBC Radio. Cited from Conner Brian, “That time Ai Weiwei flipped off the world’s most ‘important’ monuments to prove a point.” http://www.theplaidzebra.com/that-time-ai-weiwei-flipped-off-the-worlds-most-important-monuments-to-prove-a-point-photos/. Accessed 4 January 2017.

[19] Interestingly, it should be noted that the exhibition ‘Political Acts: Pioneers of Performance Art in Southeast Asia’ (11 February – 21 May 2017) at Arts Centre Melbourne presents works by artists who work in the theme of politics from every Southeast Asian countries except Thailand. Participants are Dadang Christento, Lee Wen, Moe Sott, Liew Tek Leoung, Khvay Samnang and Tran Loung, https://www.asiatopa.com.au/events/political-acts-pioneers-of-performance-art-in-southeast-asia. Accessed 22 January 2017.