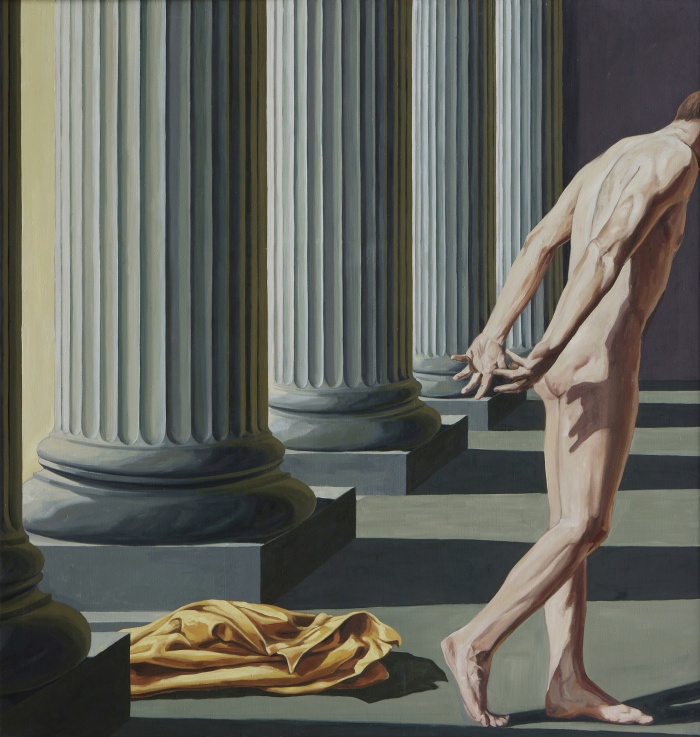

Tadeusz Boruta, Św. Franciszek oddaje się pod opiekę Kościoła, 2005 r., olej na płótnie, 210x145 cm

Tadeusz Boruta, Św. Franciszek oddaje się pod opieke Kościoła II, 2003, olej na płótnie, 200x190 cm

Tadeusz Boruta, Św. Franciszek oddaje się pod opieke Kościoła I, 2003, olej na płótnie, 200x190 cm, własność prywatna

Tadeusz Boruta, Św. Franciszek oddaje się pod opieke Kościoła, 2003, olej na płótnie, 185x275 cm

The series of paintings by Tadeusz Boruta created in 2003 titled Św. Franciszek oddaje się pod opiekę Kościoła (St Francis Entrusts Himself to the Care of the Church) depicts a naked man casting his clothes aside and entering a space occupied by Antique colonnade. A notable feature of these paintings is their monumentalism which is the result of the juxtaposition of a man’s figure with grandiose architecture – the field of vision effectively contains only pedestals, bases and lower elements of tall columns which imply the size of the building, as well as asceticism which stems from the composition comprising only three elements – nude, drapery and classical architecture. I wish to focus on two of these: the male nude and classical architecture, treating the use of these traditional artistic motifs like a provocation directed at mainstream contemporary art and culture. A provocation committed by an artist who concentrates on two areas in his art, which are not only visibly marginalised in contemporary art but even treated as counterparts: spiritualism and realistic representation of a man and his environment as derived from European painting traditions which have their beginning in Antiquity – to which he has been committed to since 1980s when he animated and participated in an independent culture movement.

As represented by the so called classical Great Theory of Beauty, it is grounded in perfect structure which in turn involves proportions of parts; initially developed as a mathematical relationship in relation to music, in the classical Greek period it also existed in relation to fine arts[1]. This idea of beauty was the foundation of classical Greek architecture and sculpture. By glossing over the nuances of this conception it can be stated that in spite of the fall of Antique civilisation it has permanently entered the perception of art of Western culture, which was evidenced by multiple cases of returning to the Antique canon of representing the human body (men in particular) and architecture.

However, neither classical architecture utilising Greek conventions nor the representation of proportionally structured human body are not an ideal according to contemporary artists and art theorists. Depictions of classical nudes are not found among pieces exhibited in institutions which provide inspiration to the contemporary artistic activities and neither is classicist architecture which despite being present in the streets of our cities, is not being utilised by contemporary designers.

Although the human body proves to be a productive topic in contemporary works of art, they are indeed characterised by the departure or even negation of the classical archetype. In this sense I am mostly referring to the mainstream contemporary art pieces exhibited and collected in major public collections. Let us look in this context a three pieces from the collection of the Modern Art Centre in Warsaw in which the motif of human body appears: Idiomy Socwiecza: Motyw ludzki I by Zofia Kulik, Oko za oko by Artur Żmijewski and Body master – zestaw zabawkowy dla dzieci do lat 9 by Zbigniew Libera. We will use this comparison to illustrate the non-representativeness of Boruta’s paintings in mainstream contemporary art.

Zofia Kulik, „Idiomy Socwiecza: Motyw ludzki I”, archiwum CSW

Zofia Kulik creates a repeated motif in large compositions, photographic carpets, utilising photographs of naked, somewhat slender male body. The body is not individualised nor is it placed in the centre where it would be able to draw attention. Quite the contrary, by assuming stiff forced poses it becomes a type, and when multiplied it is reduced to a mechanical decorative pattern. Criticism interprets this way of treating a human body as a means of presenting subordination and enslavement of a person to a soulless system which is symbolised here by socrealistic architecture of the Palace of Culture and Science. The significance of this combination of architecture and man in which the goal is the enslavement and subordination of the latter seems to be quite the opposite to the message found in Boruta’s paintings where the man freely enters the architectural space in gesture suggesting liberation or exaltation rather than enslavement.

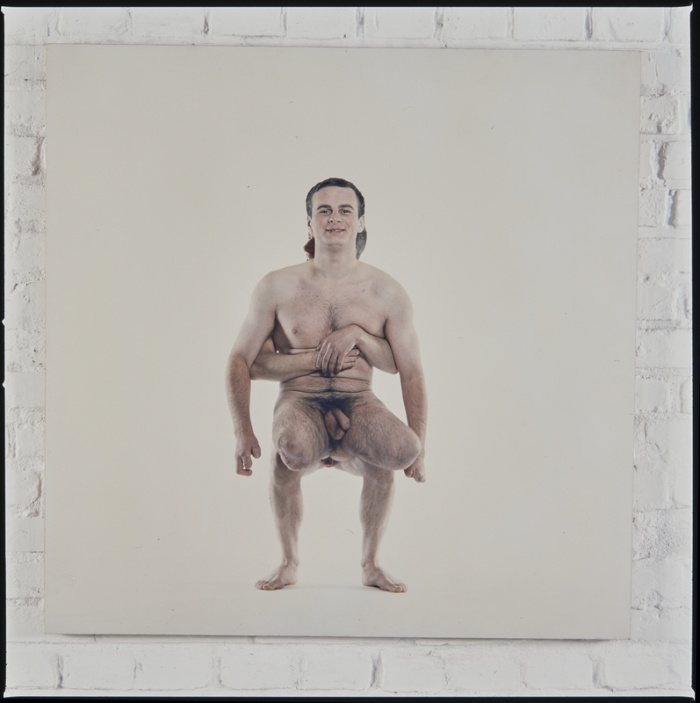

Artur Żmijewski, „Oko za oko”, archiwum CSW

Artur Żmijewski, „Oko za oko”, archiwum CSW

Artur Żmijewski, „Oko za oko”, archiwum CSW

In a cycle of staged photographs of Oko za oko, Artur Żmijewski confronts us with the view of handicapped, and healthy human bodies. A healthy person lends their limbs to the handicapped companion and thus the two bodies create one seemingly fit body. Together they form a hybrid or even a parody or a prosthetic of humanity. This is not about beauty but rather its absence. By combining such dissimilar bodies the artist highlights the frailty of the human structure as if to challenge the Creator, who was seemingly meant to create the man in his own image – as an ideal which is grounded in symmetry. The reality, however, is quite different. Beauty, which can at the least be defined as proportion which draws attention, is regarded here as something artificial at best, and at the worst as an unreal requirement that humiliates people. Żmijewski’s piece is at the same time representative to a range of similar works, such as the one by Katarzyna Kozyra, where the human body is intentionally depicted as ugly, sick and imperfect. Whereas in Zofia Kulik’s work we see a body subjected to typification, reduced to a sign of a more complex patter, for Żmijewski the body is an antitype, a body marked by stigma of existence and having its own painful history. The representation of the body in Boruta’s paintings is far from either of these. It is not reduced to a repeated pattern nor is the body too peculiar or too young or too old. Not idealised but also not deprived of fitness or proportional build. It is just a human body.

Zbigniew Libera, „Body master – zestaw zabawkowy dla dzieci do lat 9”, archiwum CSW

Let us invoke one more manner of presenting the body that is present in contemporary culture – it is the body as a product, a body sculpted by tedious exercise and meant to inspire admiration. Such a body, though represented as if seen in a distorted mirror, is a topic of Zbigniew Libera’s piece, Body master – zestaw zabawkowy dla dzieci do lat 9. The set comprises a children’s exercise kit and a board presenting the expected end result in form of a particularly muscular nine-year-old. Whereas Żmijewski parodied the classical ideal of beauty as a harmonious image of human body, Libera parodies the marketable model an amazingly muscular body which could be seen as desirable.

Compared with Boruta’s painting all three above mentioned works of art depict the modelling of human body through: 1. power – Kulik; 2. market – Libera; 3. ideal – Żmijewski. That way they suggest that by exposing and rejecting these modulators the liberation can be achieved which the artists do not show.

Liberation is depicted by Tadeusz Boruta, though the path to that goal is not the rejection of ideal but embracing it. In this sense, Boruta’s paintings go against tendencies depicted in works from the Collection of Contemporary Art mentioned above and this is what places them outside the collection, perhaps literally.

In his series Tadeusz Boruta refers to a specific event: St Francis entrusting himself to the care of the Church, but deprives this depiction of historical references. The titular St Francis becomes modernised – he takes off a rather contemporary set of clothes: trousers and a yellow shirt. Francesco Bernardone, who would become St Francis, by freeing himself from the authority of his father, a wealthy merchant, relinquishes his right to inheritance by returning him not only all money he possessed but also all his clothes. That way Francis rejected the earthly life and surrendered himself to God’s service. According to the description of bibliographers he was covered by a coat by a bishop who took him into the care of the Church through this symbolic gesture. Boruta presents his own version of the scene without a bishop, Francis’s father or a crowd of bystanders outraged by nudity – the four paintings, similarly to subsequent scenes of a film, present a nearly naked figure of a man who takes off a yellow shirt and enters deeper into the antique portico.

Boruta’s version seems to differ not only from late-medieval interpretations of the event but also our imagination as to how this symbolical scene of passage from the earthly world to the spiritual realm. From earthly desires to the sacrum. Whereas the shedding of clothes we can understand, the yellow colour symbolises gold, therefore rejection of earthly riches, the entrance into the area occupied by antique architecture is associated with the sphere of rational thought, earthly order associated with secular authority rather than spirit. We would be more likely to accept a portal of a Gothic cathedral in its place.

However, in this aspect Boruta’s version is closer to historical reality:

While visiting Assisi I was surprisingly made aware that the scene of St Francis disrobing took place at Piazza del Comune, before the antique temple of Minerva, converted into a church. That was likely the place where the future saint hid from the outraged crowd. It was a Roman portico that he must have crossed to manifest his transformation. This hagiographic moment provides even stronger symbolism of a whole avalanche of events which over time would reunite art with both realism of reality and the whole truth of human emotion as well as the classic harmony of the Antiquity.[2]

This surprising discovery became the foundation of Boruta’s aesthetic conception which is interpreted through the series of paintings with Saint Francis. It is a manifesto of a certain union of figurativism, realism and classical patters stemming from Antiquity with Christian spirituality. That what is the most impressive achievement of pre-Christian civilisation with the essence of Christianity, a certain radiance which supplemented the antique theory of beauty thanks to St Thomas. At the same time it is a demand to abolish the division between sacrum and profanum which is articulated elsewhere by Boruta:

Division between sacrum and profanum assumes a dichotomy of the world and therefore culture as well. It is the result of a prolonged process of emancipation of social and political structures and also culture as secular notions. To non-believers the idea of sacrum is usually considered in relation to the Church and its hierarchical structure as one of many social organisations. However, to religious people the entire Cosmos has sacral character. Their actions, thoughts, private and public life are religious. Sacrum does not remain behind the doors of a church. Even sin or the existence of the devil are the result of religious relationship. Judging it from the point of view of a believer, profanum does not exist as an opposition to sacrum. Only Sanctissimus can be distinguished as a place of a special presence of God.[3]

The scene from life of St Francis interpreted by the painter symbolises a revolutionary artistic transformation which began with Giotto’s frescos would develop into the art of Italian Quattrocento. However, Boruta creates his canvases in a completely different social, religious and aesthetic context. Can they be treated in terms of radical cultural utopia? Attempts of decisive opposition to the spiritual and cultural trend of contemporary times? In the broader sense this would be a proposal for restoration of the relationship of the man with the world, the key to which would be the Antiquity-derived aesthetic ideal of beauty.

This utopia would be in opposition to the utopian school of thought of the post-modern culture. This can be seen in the comparison of the image in contemporary art and Boruta’s paintings as previously described. Perhaps this would be even more noticeable in the clash of the architecture found in Boruta’s paintings with that which occupies the contemporary human space. It does not concern exclusively secular architecture in which the historicist styles, characteristic even during the early 20th century have now been eliminated but also the sacral architecture.

The overview of modern sacral architectural trends can be found in Jakub Turbas’s book, Ukryte piękno. Architektura współczesnych kościołów[4]. The author picks 18 examples of Catholic Church architecture which he considers to be the most notable. Among all these creations, the stylistic reductionism can be pointed out as a common property, which is manifested as a departure from various traditional architectural elements, emphasising to the point of showing off the raw properties of the used materials and structuring the buildings in form of a compact shape or with the use of more or less complex composition of solids. Therefore, the sacral character of architecture is expressed in simplicity, minimalism, avoidance of decoration and elements breaking up the wall surfaces to display the naked material. It could be said that in some way it is honest architecture – in the same sense as the image of the body in critical art: devoid of any organising canon – all forms of canon, a top-down order would connote falsehood – referring to the displayed nakedness of the material and simplicity of geometry which, however, is in a certain sense flawed, rough, tainted with imperfection.

A characteristic feature of these buildings is that none of them has any traditional columns, pilasters or pillars with distinct base, shaft and capital, as if those elements were subject to unwritten prohibition which excludes them from the area of contemporary sacral architecture. They constituted a certain costume of falsehood which had to be shed, not unlike St Francis clothes, in order to fulfil ethical norms of contemporary times.

In other words, if Tadeusz Boruta wished to keep up with the times, he should have placed his protagonist not within an antique portico of the Assisi temple but against the façade of a contemporary church built in the adjacent Foligno by Massimiliano Fuksas and his wife Doriana. It seems that of all the buildings described in Jakub Turbas’s book, this building is the most in-line with the spirit of our times. St Francis of today would stand not before a classical portico but an enormous flat wall assembled out of almost a hundred concrete slabs, with a crevice-entrance at the bottom. There are no separating elements here, no symbols, no markings. The whole church is built in form of a concrete box. Windows – irregular trapezium-shaped slits distributed on the wall – are placed only on the side façade. This is architecture reduced to the simplest forms, as if it was stripped of not only all the historical stylistic elements but also escaping the division into floors, rhythm of elevation created by cornices and windows, etc. This is aesthetics or rather anti-aesthetics based on negation, seeing development as removal of detail, simplification or levelling of the structure.

Kościół San Paolo Apostolo w Foligno, źródło: www.commons.wikimedia.org

Kościół San Paolo Apostolo w Foligno, źródło: www.commons.wikimedia.org

Adolf Loos in a famous essay titled Ornament and Crime wrote:

I have discovered this truth and I have given it to the world: the evolution of culture is tantamount to the removal of ornaments from utility items. […] Behold, the time of our satisfaction is near. Soon the city streets shall glisten like white walls! Like Zion, the holy city, the capital city of the heavens. Then the fulfilment shall come.

Although this architect did not negate the significance of Roman architectural tradition during his time, his words which associate the progress of culture with rejection of historical stylistic and decorative elements in utilitarian art have become an indicator of progress in art and architecture of the 20th century. The aforementioned church in Foligno is not at all an example of avant-garde architecture. In fact the appearance of its façade looks nearly identical to the elevation of large panel blocks of flats which can be found in great quantities in Polish cities. The entrance of the building, in turn, resembles a hall of a railway station or a bank. The architecture of the church not only sets out trends for other projects as it often was in previous eras but also becomes absorbed by the commonplace surrounding architecture. We see it as a gesture of rejection of what has been regarded as unnecessary by people of today and therefore as sinful, transferring the accent from aesthetics to ethics.

Why would the historic architecture in form of column portico be sinful? Let us address the main fault – negative connotations regarding its association with totalitarian regimes, especially the Third Reich. Socrealism, similarly to communism, seems to evoke less controversy. Art resorting to the presentation of academic human nude and architecture inspired by classical antique patterns not constituting an ironic remark now bears a cultural stigma of participation in a crime committed alongside those who regarded it as their own and included it in their project of forging a new totalitarian order. Nudes in art and porticoes in architecture will continue to be associated in public awareness with crimes of Nazi Germany as if those crimes were committed by the figures in the paintings. Therefore – just as biblical Adam and Eve – they have to be removed from the paradise of contemporary culture and shall wear the fig leaf of avant-garde deformation and distance, in fact avant-`garde and modernism, branded as degenerated art by the Nazis, gained their ethical value because of it.

München, Haus der Kunst, źródło: www.commons.wikimedia.org

Notable in this context is the discussion regarding the renovation of Haus der Kunst in Munich. By the order of Hitler the building was erected in 1937 by Paul Ludwig Troost and named Haus der Deutschen Kunst. The façade is decorated by a monumental column portico inspired by Schinkel’s Altes Museum in Berlin. After 1945, this column portico was obscured by a row of trees planted in front of the building. David Chipperfield, who was tasked with the renovation of the building decided to uncover the colonnade and thus once again rejoin the building with the structure of the city from which it was somewhat excluded. However, that plan was met with protests. The architect was accused of glorifying Nazi architecture and therefore soiling the memory of the victims of German Nazism. The critics admitted that the building itself is not a threat but the national socialism manifested and connoted through it is responsible for death of millions of people[5]. Furthermore, it can be added that socrealist architecture present in many cities of Central and Eastern Europe does not arouse as great controversies, though if we were to associate buildings with the ideology of their builders we would have to admit that their presence is far more problematic, proportionally to the greater numbers of victims of the communist ideology. In response to these accusations Chipperfield likely approached crucial causes of stigmatisation of not just Nazi architecture but also the erasure of historicist classical aesthetics from contemporary architectural practices.

Criticism of the current proposition [of the renovation of the building – P.B.’s note] is not as much caused by the description of reorganisation of the building’s interior as by the philosophy of the reopening of the building to the city through the removal of the trees […]. The return to the previous arrangement of the surroundings was met with an accusation of ‘glorification of Nazi architecture’. That is the heart of the issue. The removal of the trees questions the need for hiding the building. We ask whether it is still necessary to hold onto that ‘fig leaf’.[6]

That question from Chipperfield is in my opinion fundamental. The answer does not come from the sphere of aesthetics but politics, though it does directly affect the former. Holding onto the ‘fig leaf’ is the result of controlling the political scene by parties and political circles who find the threat of the rebirth of fascism of National Socialism still relevant in the current democratic political order. Paradoxically, the more distant the heinous times of the Third Reich, the more emphasis is put on the relevance of that threat. Again we can observe that although communism is a more historically recent past, no warnings about the potential return of totalitarian communism have the same cultural impact as warnings about fascism. This metaphorical fig leaf of cultural shame which has been stretched over the classicist portico of the museum in Munich can be understood more broadly as stigmatisation of classicist patterns in general. In accordance with this politically inspired narration, embracing classicist architecture or traditional nudes in painting would suggest the threat of the return of murderous ideologies and therefore further highlight the need for keeping that fig leaf. What we have here is a new type of politically relevant association of aesthetics and ethics, a new division into certain sacrum and profanum. The former will involve reductionist modernism, escaping the patterns, the ideal, whereas the profanum shall be marked by historical and classicist patterns and the accompanying notions of searching for the ideal, canon, order.

Therefore, we can state that escaping or avoiding classicist patterns as contaminated through their employment by criminal regimes, which permeates contemporary art and architecture, is determined by the political taboo[7]. There is a neutral question to ask – is art allowed to approach such a taboo?

This is exactly how Tadeusz Boruta’s series seems to operate. It is not only critical in the sense of challenging the dogma of contemporary art, tearing off the fig leaf of shame which covers the representation of human body in contemporary art and historicist classicist architecture. The cycle goes one step further – by not simply defying the current political artistic paradigm but also indicating that it is possible with the use of a non-political foundation. Such foundation, as seen in Boruta’s series, is the Church, and more broadly, Christianity. By returning to Christianity, as Boruta seems to advocate, it is also possible to return to classicist patterns and escape the vicious circle of aesthetic negation.

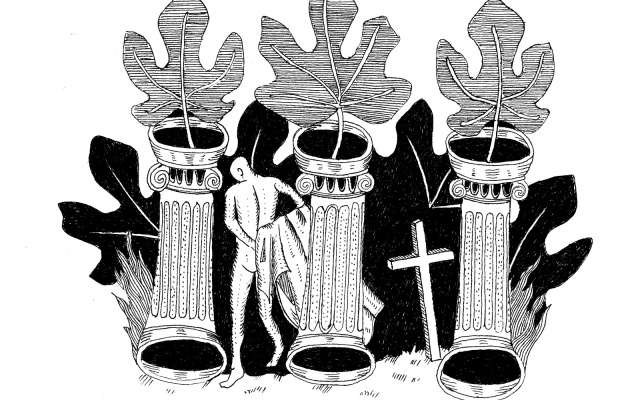

Drawing: Ignacy Czwartos

[1] W. Tatarkiewicz, Dzieje sześciu pojęć. Sztuka, piękno, forma, twórczość, odtwórczość, przeżycie estetyczne, PWN, Warsaw 1988, pp. 142–143.

[2] T. Boruta, O malowaniu duszy i ciała. Szkice o sztuce, publ. Jedność, Kielce 2006, p. 50.

[3] Ibid, pp. 86–87.

[4] J. Turbas, Ukryte piękno. Architektura współczesnych kościołów, Towarzystwo “Więź”, Warsaw 2019

[5] Ella Braidwood, Chipperfield defends proposal for Nazi-era Haus der Kunst, [in:] Architects’ Journal, 24 January 2017.

[6] Ibid.

[7] This would indicate that lifting the taboo would be possible by operating within that area. According to the politics of affirmation of minorities and sexual disorientations it is possible to lift the taboo precisely in that aspect of representation of the political homosexual minority. An example of that is, for instance, the publication Nagi mężczyzna. Akt męski w sztuce polskiej po 1945 roku, affirming nude art from homosexual perspective.