In their recent exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, The Propeller Group, an artist collective based in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, installed a two-channel video work titled “The Guerillas of Cu Chi,” (2012) that consisted of a 1963 Hanoi-produced propaganda documentary facing, on the opposite wall, a film taken by the three artists of tourists conducting target practice at the same site’s shooting range. The tunnels of Cu Chi, an intricate 121-kilometer long underground complex of chambers and passageways, were part of the Viet Cong’s “weapons” of defense, one of their most successful strategies in alluding the air raids and bombs dropped by US forces during the decades of war between the two countries. They are among the most popular tourist destinations in Vietnam today. The irony is not lost on the artists whose work often plays with the slippery boundaries between reality and fiction. That the “real” site is now a playground for tourists to shoot “fake” bullets, and the “real” footage of the “real” soldiers hiding underground is placed across it as if it were the “fake” target of the tourists’ game and was a prop for a staged reenactment instead of the “real” deal. In my view, it also perfectly captures the ways in which art and war intersect in Vietnamese art history. For decades, war was the only visual reference that international viewers had of the country and stood as the most recognizable symbol of Vietnamese cultural identity. And yet, Vietnamese artists within Vietnam rarely made explicit references to the war, choosing instead to focus on themes of nation-building by portraying domestic scenes, landscapes, and portraits of their families. So, outsiders came to associate Vietnam with the war while those that experienced war firsthand chose to avoid it. This short essay will offer a few examples of how the trope of war is played out by some contemporary Vietnamese artists as a means of challenging dominant nationalist narratives promulgated by both official and popular public discourse.

War is a powerful subject for any artist, and since the 1960s, has been explored in a variety of forms by Vietnamese and American artists on both sides of the conflict. The American-Vietnam War has become the subject of countless memoirs, history books, political biographies and art works, both in protest of the war by American artists and in its defense by North Vietnamese. The former includes Leon Golub, Nancy Spero, and more famously Martha Rosler with her photo-collages of middle class American domestic scenes interrupted by invading troops popping out of television screens literal playing with the slogan “the war comes home.”1 While those works were created during the 1960s and 1970s, when combat was in full swing, a number of contemporary art works have been produced by artists such as The Propeller Group and other Vietnamese immigrants who settled in the United States. As Viet Thanh Nguyen has observed “much of the writing, art, and politics of Vietnamese refugees, is about the problem of mourning the dead, remembering the missing, and considering the place of the survivors in the movement of history.”2 The artists that form The Propeller Group: Tuan Andrew Nguyen (b.1976), Phunam Thuc Ha (b.1974), and Matt Lucero (b. 1976) chose to settle, and in the case of the former two, resettle, in Vietnam because the country provides endless source material to explore, play with and exploit. Their move in 2006 succeeded several other returning 1.5 generation Vietnamese artists such as Dinh Q. Lê (b. 1968), Jun Nguyen-Hatsushiba (b.1968), and Tiffany Chung (b.1969). While many of the artists were interested in the “new Vietnam,” some were compelled to revisit the ways in which the war had penetrated the American psyche. Dinh Q. Lê, for example, created a series of works that interwove stills from Hollywood movies with photographs that appeared in the American media during the war, while Jun Nguyen-Hatsushiba produced a series of underwater videos that commemorated the so-called “Boat People” that risked their lives at sea after fleeing their war-torn country. These works were visible on the international biennale and contemporary art circuits for several years.

Dinh Q. Lê, Światło i wiara: szkice z życia podczas wojny wietnamskiej, dOCUMENTA (13), 2012. Za uprzejmością artysty

Dinh Q. Lê, Światło i wiara: szkice z życia podczas wojny wietnamskiej, dOCUMENTA (13), 2012 3. Za uprzejmością artysty

Dinh Q. Lê, Światło i wiara: szkice z życia podczas wojny wietnamskiej, dOCUMENTA (13), 2012. Za uprzejmością artysty

The Propeller Group, Guerilla z Cu Chi, 2012. Za uprzejmością artystów

More recently, Dinh Q. Lê, however, chose to look back, not at the war imaginarily but at the art that was made during the time of war on the side of the Vietnamese. His installation “Light and Belief: Sketches of Life from the Vietnam War” at dOCUMENTA (13) in 2012, consisted of drawings made by North Vietnamese artists who followed the guerilla movement along the Ho Chi Minh trail in the 1960s and 1970s. The artist culled these works from his own collection and exhibited them along with a video made in collaboration with The Propeller Group that captured interviews with the surviving artists and digital animations of the drawings as if they were made in front of the viewer’s eyes. The animated reconstructions of the drawings literally brought the drawings to life and made them appear to be reenactments of actual events. While the sketches were originally made as preliminary drawings for larger paintings commissioned by the Vietnamese Artists’ Association and the Ministry of Culture, due to the isolation imposed on Vietnam in the decade following the war, the international art world did not catch a glimpse of them until the Drawing Center in New York organized an exhibition of what they called “persistent vestiges” in 2005. The exhibition curators, in the accompanying catalogue, proposed them as an alternative to the violence infused photographs familiar to all Americans who had lived in the 196s and 1970s. The sketches were seen as a kind of repair for the trauma suffered by the Americans and an atonement for the Vietnamese who suffered great losses. The curators noted the lack of violence in the drawings and stated:

“It is remarkable, therefore, that instead of depicting violent combat scenes and details of the American-Vietnam War’s brutality, all chose to capture everyday moments from military and civilian life. An extraordinary sense of calm and quiet, of idealism, pervades the works, which include depictions of soldiers working, gathering, or relaxing in the landscape.”3

Dinh Q. Lê’s intent in displaying the sketches was somewhat different. He sought to question the continued relevance of Ho Chi Minh thought in contemporary Vietnam. In an email, he revealed that he felt “these artists seem to be living in a world removed from reality. Their belief in Hồ Chí Minh and the communist party leaders, during the war and now, seems very cultish. It is so hard for me to understand their blind belief but it helps me understand clearly how these surreal drawings came into being.”4 That the artist found these drawings “surreal,” confirms the often blurred lines between reality and fiction that continues to plague the representation of the Vietnam war. The New York based artist An-My Le (b. 1960) gained recognition in 1999 for a series of photographs of war reenactors in Virginia. The series titled “Small Wars,” dated from 1999 to 2002, captured men who spend their weekends reenacting battles from the Vietnam War in the forests of Virginia. According to the catalog of an exhibition of her photographs that took place in Chicago “While her pictures present men – some of them veterans, others history buffs – as they simulate combat and war routines using detailed props such as grounded airplanes, tents, and uniforms, the images do not include the glaring anachronisms that may have been present. It is the landscape that provides the most telltale signs of falsehood: the flora is typical of North American pine and oak forest, nothing like the dense, tropical jungle that covers much of Vietnam. Le was often asked to participate in the reenactments, her ethnicity presumably adding an element of authenticity to the make-believe. She performed for the male audience that became, in actuality, her real subject. Sensitive to the fact that what motivates such men is often a complex web of psychological need, fantasy and a passion for history, Le did not make a mockery of their actions.”5

An-My Le, Małe wojny - lekcja, 1999-2002. Za uprzejmością artystki

An-My Le, Małe wojny - akcja ratunkowa, 1999-2002. Za uprzejmością artystki

The ambiguity of Le’s photographs raises questions about the reliability of seemingly objective historical accounts such as news photographs which greatly influence how war is communicated and remembered. She uses a large format camera that recalls early war photography such as Civil War photographers who were interested in achieving a level of clarity and craftsmanship to heighten the sense of direct reportage. Many of those photographs arranged some of their scenes aesthetically thus pointing to the history of war imagery that blends reality and artifice that is precisely An My Le’s goal in photographing not real combat, but staged battles. The Propeller Group’s “Guerillas of Cu Chi” operate on similar premises. In using tourists as actors in their portrayals of the site of Cu Chi, they are highlighting the contradictory ways in which humans behave when confronted with toy guns and the hypocrisy when it comes to war, and the inability to distinguish truth from fiction.

These examples point to the way in which war provides fodder for artists in their investigations into the costs and consequences of war. While satire may seem like an apt critique of the ways in which war has been mediated and fantasized, some artists prefer to point at the truth. Danh Vo (b.1975), who grew up in Denmark, has acquired various artefacts and historical relics dated to the Vietnam war era in order to more directly address the legacy of war and its memory. Where other artists look figuratively at the war, Danh Vo examines it more literally. In 2012, he displayed letters that he had purchased at auction that were signed by Henry Kissinger, typed onto White House stationary. The letters were sent in thanks for tickets that a certain Leonard Lyons had offered to the Secretary of State and one of them, dated May 20, 1970, read: “Dear Leonard, you must be some kind of friend. I would choose your ballets over contemplation of Vietnam any day if only I were given the choice. Keep tempting me, perhaps one day, I would succumb. Warm regards, Henry A. Kissinger.”6 The letter is remarkable in that Kissinger casually refers to the “secret war” on Cambodia as if it were an ordinary annoyance. But, what is more remarkable is Danh Vo’s display of them without any contextualization. Not that there is any need for it, they speak for themselves but mostly by association. The letters do not directly speak of war or policy toward Indochina but they stand witness to the time when the strategies toward Vietnam were implemented and to the man behind them.

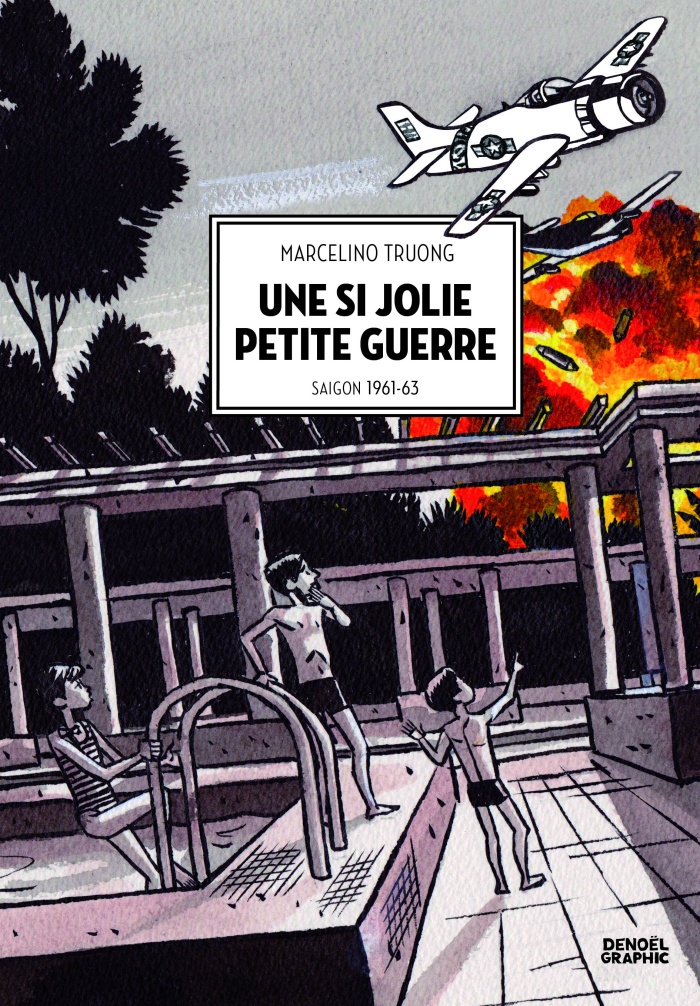

Marcelino Truong, Okładka Une si jolie petite guerre (2012). Za uprzejmością artysty

Danh Vo, 16-32, Żyrandol z końca XIX wieku, 2009. Za uprzejmością artysty

Danh Vo’s objects act as relics of history but they are also substitutes for personal biographical objects that didn’t survive. His acquisition of them is the equivalent of museumizing them, enshrining them, encasing them. Danh Vo and his family fled from Vietnam by boat and were rescued at sea by a Danish ship. After a time in a refugee camp in Singapore, they settled in Denmark. His interest in historical objects may be related to the condition of being a refugee and the need to store objects of value when faced with the unpredictability of forced migration. Bu, they also signal the artist’s need to tell a story, his and his family’s story, albeit in an oblique manner, through the use of archival objects. The archival impulse made popular by Hal Foster notwithstanding, one could see these artists as mining history out of a desire to recover, or reclaim, the past. While The Propeller Group use irony in order to explore truths, the French-Vietnamese graphic novelist Marcelino Truong (b. 1957) mines his own truthful biography to toy with the fictions of war. His duology “Such a Lovely Little War” and “Give Peace a Chance,” recount in drawing, the period of his life that he spent as a boy in Saigon, between 1961 and 1963 and then in London 1963 to 1975.7 The panels are made up of anecdotal memories of his family life during the war and are interspersed with archival material, juxtaposing official history with personal recollections. In one panel, he and his brother are playing with toy guns and taunt each other over their supposed affiliations with the communists versus the RVN. In another, he imagines the crickets chirping outside of his bedroom to be the sound of bullet fire.

If war is made to appear like a game to these artists, it is because, as Dinh Q. Lê alluded, it can seem surreal both to those who experience it and to those who witness it. The tourists in The Propeller Group’s “The Guerillas of Cu Chi,” don’t seem to realize they are reenacting actual firing squads. But, the artists seem to be saying, the propaganda footage looks similarly unreal. Only personal testimony and biographical records can act as validation of the past. For all of the aesthetic associations between war and nationalism that have been played out in contemporary art, the game of identity politics is effectively reduced to individual stories.

BIO

Dr. Nora A. Taylor is a specialist in Vietnamese Modern and Contemporary Art and the Alsdorf Professor of South and Southeast Asian Art at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She is the author of Painters in Hanoi: An Ethnography of Vietnamese Art (Hawaii 2004 and Singapore Press, 2009) and co-editor of Modern and Contemporary Southeast Asian Art: An Anthology (Cornell SEAP Press 2012) and editor of Studies in Southeast Asian Art: Essays in Honor of Stanley O'Connor (Cornell SEAP Press 2000) as well as numerous articles on Modern and Contemporary Vietnamese and Southeast Asian Art. She was also curator of “Changing Identity: Recent Work by Women Artists from Vietnam” for International Arts and Artists, and “12,756.3: Breathing is Free, Recent Work by Jun Nguyen-Hatsushiba,” at SAIC and ASU Museum of Art. In 2014, she was the recipient of a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship for research on the politics of Performance Art in Vietnam, Singapore, and Burma

*Cover photo: The Propeller Group, Guerilla z Cu Chi, 2012. Courtesy of the artists.

[1] The Vietnam war was known as the first war to receive such wide television coverage allowing viewers to watch reports of the violence taking place in Southeast Asia from the comfort of their homes.

[2] Viet Thanh Nguyen, “Speak of the Dead, Speak of Vietnam: The Ethics and Aesthetics of Minority Discourse,” CR: The New Centennial Review, Volume 6, Number 2, Fall 2006, p. 8.

[3] Persistent Vestiges: Drawings from the American Vietnam War, ed. Catherine DeZegher, The Drawing Center, 2005, p. 13.

[4] Personal email communication from Dinh Q. Lê, September 11, 2013.

[5] Karen Irvine, “Under the Clouds of War,” Chicago, Museum of Contemporary Photography, October 27-January. 6, 2007, http://www.mocp.org/exhibitions/2000/6/an-my-le-small-wars.php, accessed November 1, 2016.

[6] The exhibition “Danh Vo: Uterus” took place at the University of Chicago’s Renaissance Society, September 23-December 16, 2012.

[7] Marcelino Truong, Une si jolie petite guerre, (Paris: Denoël), 2012; Marcelino Truong, Give Peace a Chance, (Paris: Denoël), 2015.