Throughout its history Ukraine has been constructing politics, entering alliances with the East or the West, and searching for its own middle path. Double articulation, as an attempt to find itself, characterizes Ukraine geographically and historically. Seeking unity, Ukraine finds it hard to admit the complexity of its own identity, and the Maidan events have revealed a complex, long-lasting conflict associated with a clash of different concepts of the world and stereotypically developed ideas about the East and the West (read: Russia and Europe) on the level of both symbols and political forces. It seems that artistic practice combines these two levels: reacting to political forces, the artist expresses his/her attitude through the language of art. However, the tragic nature of the Maidan events demonstrated that art is powerless in the face of real violence.

We spoke with Sergey Bratkov and Yuri Leiderman, two artists who came to the fore in the late 1980s, at the end of the USSR’s existence: one in Kharkov, the other between Odessa and Moscow. They both have complex identities and are important opinion-makers for Ukrainian art as well as various artistic and intellectual communities. Bratkov is a citizen of Ukraine who lives in Moscow; Leiderman is a citizen of the Russian Federation who lives in Berlin. Both are embodiments of the historic Ukrainian ambivalence.

We asked them about how they perceived their experiences of the Maidan events, about how the clashes of perspectives and worldviews were reflected in art, in their relationships with their colleagues, and why these events helped turn many contemporary art practices into “excavations” of historical correctness.

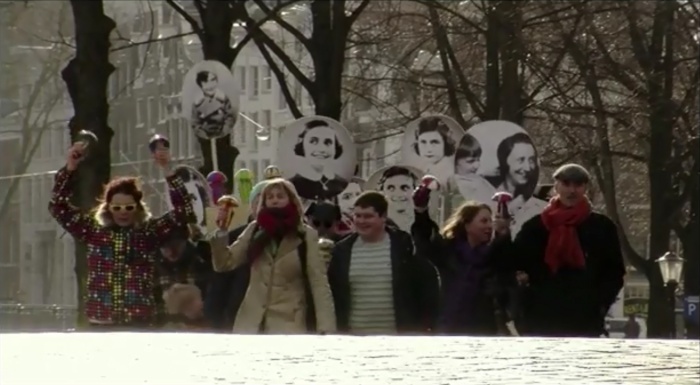

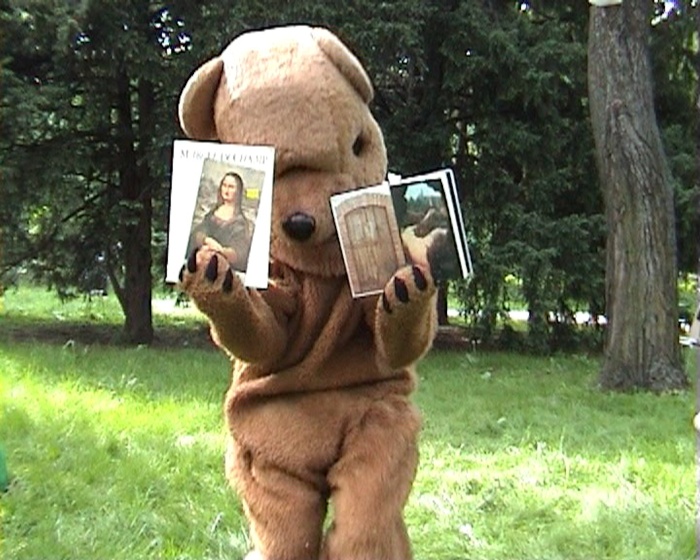

Jurij Lejderman, Geopoetyka I, 2003. Czarno-białe fotografie na drewnianych panelach, performans. Zdjęcie: Siergiej Ilin, (c) PinchukArtCentre, 2016.

Jurij Lejderman, Geopoetyka I, 2003. Czarno-białe fotografie na drewnianych panelach, performans. Zdjęcie: Siergiej Ilin, (c) PinchukArtCentre, 2016.

Jurij Lejderman, Geopoetyka I, 2003. Czarno-białe fotografie na drewnianych panelach, performans. Zdjęcie: Siergiej Ilin, (c) PinchukArtCentre, 2016.

Tetiana Zhmurko: Few people could remain indifferent to the revolutionary events of the Euromaidan in November–December 2013. Information about them took over the front pages of the media across the world. What shaped your perspective of the events at that point? How was it possible to make up your own mind about what was happening amid all the different opinions, conflicts, arguments, and disputes?

Yuri Leiderman: I think there is no objective, neutral information at all. In anything related to politics in any case. And especially in a revolutionary situation, which, by definition, is an escape from the established legal field and a realization of a deeper right – “the right to an uprising.” In these events, we “filter” information to begin with and perceive what we want to hear, what matches our worldview, our orientation, our hope, or our hate. My views were originally liberal, pro-Ukrainian, pro-Western, anti-Putinist, so I did not have to “figure out” what was happening for myself beforehand. I only remember the desperation, humiliation, literally on a personal level, which I experienced when Yanukovych refused to sign the EU Association, and the relief, pride, and hope when people started to gather in the Maidan. In addition, at least since the period of the Orange Revolution, I had followed news from Ukraine quite closely, almost on a daily basis. So I knew and I was used to reading the media whose editorial policies were more in accordance with my own position.

Moreover, at some point, I myself partly became a source of information. I joined the initiative group Ukrainians in Berlin, which managed to organize, among other things, “an alternative Ukrainian embassy” (the actual embassy was still subordinate to Yanukovych). Essentially, of course, it wasn’t an embassy, it was a kind of information point. We manned it in shifts. People came in, passersby – Germans, foreigners – they asked what was going on in Ukraine after all, or how they could help the Maidan. I talked with them and then dutifully recorded their questions in the “shift log.” Under the impression of those conversations, as well as private debates with people I knew, I was suddenly prompted to write an “open letter.” It went viral online under the headline someone else gave it, A Letter on the Ukrainian Revolution, Written in Russian. For a few days, it was among the most popular posts in the Ukrainian blogosphere; according to my estimates, about forty thousand people read it. People from the Maidan wrote to me, my first primary school teacher wrote to me from Odessa: “My family and I subscribe to every word of it! I’m proud of my students!” and so on and so forth.

Jurij Lejderman, Grenlandia, 1988. Dzięki uprzejmości artisty.

Of course, I was glad that I managed to write something useful – glad, but and at the same time embarrassed. The thing is that all my life, I’ve worked professionally not just in fine arts, but also in literature. My books were usually written in complex modernist prose, they were published, got good reviews, were nominated for literary prizes, but clearly, the number of readers of this literature is vanishingly small. So, on the one hand, my texts, which I polished for months, painstakingly considering if I should put a comma or a semicolon, are basically not needed by anyone; on the other hand, the Letter on the Ukrainian Revolution, written in 15 minutes, where, as I thought, I expressed such obvious things (“Yes, I’m a Russian speaker, I’m Jewish, I’m from Odessa, but that is exactly why I am Ukrainian!”) was so widely well-received! In fact, I tend to think this is the artist’s fate: always residing in the gap between being needed and not needed, being in demand and not in demand; there is nothing special about it, but the revolution really actualizes this gap, it turns it into your opportunity to choose, act, take action. Even if this action seems so obvious to you, so simple, “not artistic.”

The revolution and the events that followed, such as the annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas, caused numerous conflicts in art circles. Did they affect your relationships with your colleagues, and was it reflected in your art? How effective, in your opinion, is the method of boycott, used in situations of conflict?

I should probably talk here primarily about my many friends and colleagues in Russia and Moscow, although not only them. Most of my friends and acquaintances, of course, were part of the liberal circles – otherwise it would be strange for them to be my friends – and they were more or less sympathetic towards Ukraine. I broke things off with those whose views were different, without any regret. Still, even many of the Ukraine sympathizers were not without a dash of the typical Russian “condescension” – they treated the events in Ukraine, the Ukrainian identity itself as a kind of fantasy – yes, a positive one, yes, deserving attention, but still somewhat fanciful. In any case, none of them took any real action in support of Ukraine. So, unfortunately, I think I was the only one who refused to work with the state art institutions of the Russian Federation, who protested against holding the MANIFESTA Biennale in Saint Petersburg, who mocked the acquiescent position of its curator Kasper Konig, and so on. In Moscow, as far as I know, the majority treated this with just friendly condescension: “Well, Yura’s lost his mind in his Ukraine.” However, I want to take this opportunity to mention and thank a few colleagues who supported my position over MANIFESTA 10 – Dan Perjovschi from Romania, Paweł Althamer from Poland.

For me personally, it’s not that important how effective the methods of boycott and breaking off relations are. Because I did these gestures not for any kind of “effect,” but, as they say, to clear my own conscience, just because I couldn’t do otherwise. On the other hand, however, it’s obvious to me that, say, in Russia in the late 19th century, any intelligentsia member, director of a museum, a theater, a publishing house would think a thousand times before speaking in support of the tsarist regime. Mostly because he knew he would risk finding out on the next day that he had no authors, artists, performers anymore, that he would be ostracized and boycotted. That is why there was a “revolutionary situation” and “sociopolitical rise,” or whatever it was called, in Russia back then, and now there’s just the dull “Putinism.”

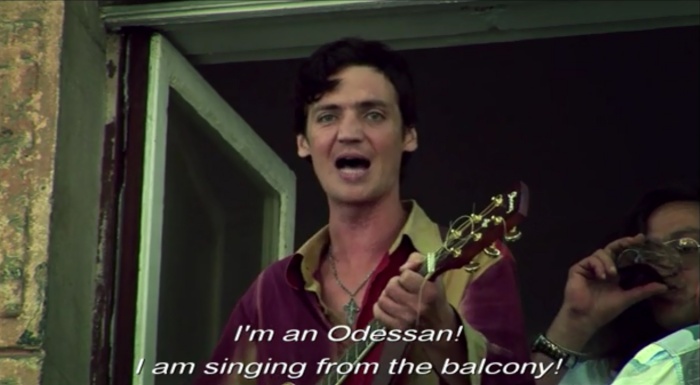

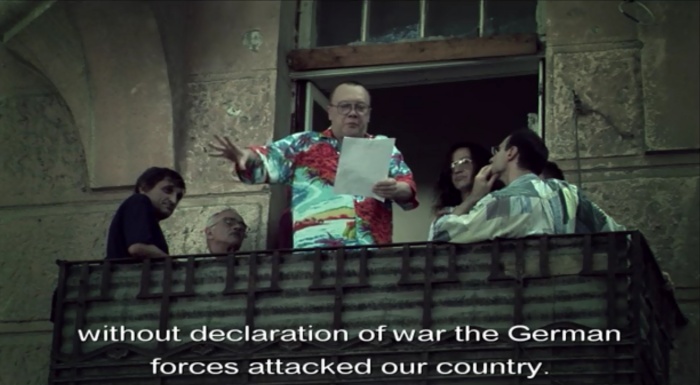

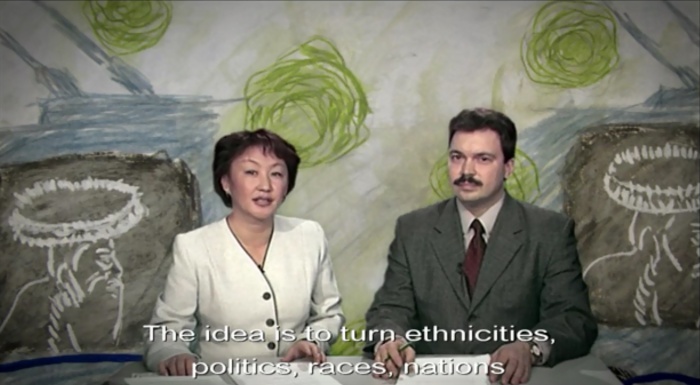

Jurij Lejderman, Andriej Silwestrow, kadr z filmu Birmingham Ornament, 2011. Dzięki uprzejmości artystów.

Jurij Lejderman, Andriej Silwestrow, kadr z filmu Birmingham Ornament, 2011. Dzięki uprzejmości artystów.

Jurij Lejderman, Andrej Silwestrow, kadr z filmu Birmingham Ornament, 2011. Dzięki uprzejmości artystów.

Jurij Lejderman, Andriej Silwestrow, kadr z filmu Birmingham Ornament, 2011. Dzięki uprzejmości artystów.

Jurij Lejderman, Andriej Silwestrow, kadr z filmu Birmingham Ornament, 2011. Dzięki uprzejmości artystów.

Jurij Lejderman, Andriej Silwestrow, kadr z filmu Birmingham Ornament, 2011. Dzięki uprzejmości artystów.

Jurij Lejderman, Andriej Silwestrow, kadr z filmu Birmingham Ornament, 2011. Dzięki uprzejmości artystów.

Jurij Lejderman, Andriej Silwestrow, kadr z filmu Birmingham Ornament, 2011. Dzięki uprzejmości artystów.

You developed as an artist in the late 1980s–early 1990s, the time when the USSR was collapsing. Was the question of identity important for you back then, and what is the role of citizenship in it?

Indeed, in the 1990s, when the Soviet Union was collapsing, I lived in Moscow and I automatically got Russian citizenship. Still, I followed the events in Ukraine very closely and liked to emphasize that I was a “Ukrainian artist.” However, I also didn’t object too much when I was presented as a “Russian artist.” In the period of Yeltsin’s relatively liberal, pro-western rule, all these matters of passports and identification did not seem very significant. As Putin’s regime deepened, it became more serious. 2008–2009 (if I’m not mistaken) were the breaking point years for me, when Russia blocked Ukraine from joining NATO and occupied Georgian territories. I realized that Ukraine was going to be next, sooner or later, and that I risked ending up in a country at war with my homeland. That is why, to a large extent, I took my family from Moscow in those years and, you could say, moved to Germany for good. Although, once again, my friends from Moscow tended to accuse me of paranoia. But, unfortunately, those predictions turned out to be justified.

Going back to the topic of national identity, with which I’ve worked a lot in my art projects, I believe that a person’s identity, in contrast to the identity of an animal or some kind of product, isn’t something given to them, ironclad, thrown down from the top. On the contrary, national identity is our choice, our struggle, it is like a poem written by each of us with our lives. Not everyone has the gift of being a poet or an artist in the conventional sense, but our identity, as something that is always becoming, as an inquiry, as an orientation to the future, as hope – it is entirely at the creative disposal of each of us.

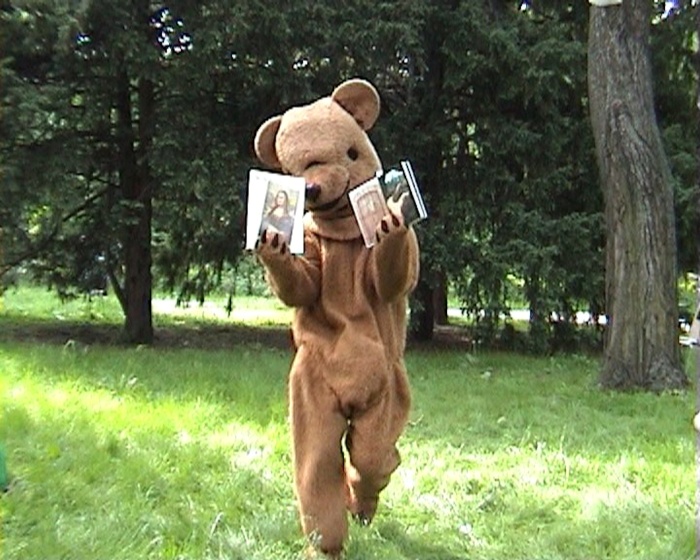

Jurij Lejderman, kadr z wideo Chasydzki Duchamp, 2002. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

Jurij Lejderman, kadr z wideo Chasydzki Duchamp, 2002. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

Jurij Lejderman, kadr z wideo Chasydzki Duchamp, 2002. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

Jurij Lejderman, kadr z wideo Chasydzki Duchamp, 2002. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

Jurij Lejderman, kadr z wideo Chasydzki Duchamp, 2002. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

In this sense, someone can totally have several national identities. After all, who among us wasn’t an Indian, an ancient Greek or someone like that when he was a kid… I can totally imagine a situation – and it actually happened – when I quite easily and happily could consider myself both a “Ukrainian” and a “Russian” artist, as well as “Jewish,” “German” or even almost “skaldic” (I was very passionate about ancient Icelandic poetry), and when I was asked clarifying questions, I answered: “Don’t bother me, I’m just a Jewish boy from Odessa.” But all of this is probably more appropriate for situations of relative peace and prosperity. However, when one part of your identity starts to contradict another, when there’s war against your homeland and its very existence is threatened, you obviously have to make a choice.

After the revolutionary events, the so-called “memory battles” and deliberations about the past happened. The practice of many young Ukrainian artists is based on a conceptualization of the historic processes of the past. What is the reason behind this orientation, and what is important in art for you?

I like to quote a phrase from the French socialist historian Jean Jaures: “We can take from the past its fires, and not its ashes.” Objective, neutral past – just like the “information” which we started with – doesn’t exist. The past is always happening here and now. We choose our past, the “past” of our nation, based on how we want to see it in the present and the future, it’s the material from which we construct our “present.” Of course, this doesn’t mean rejecting or diminishing the work of historians. On the contrary, we need facts, we need knowledge, which, as we know, is “power.” But collective myths are just the thing that prevents each of us from making our own clear and, at the same time, personal choices.

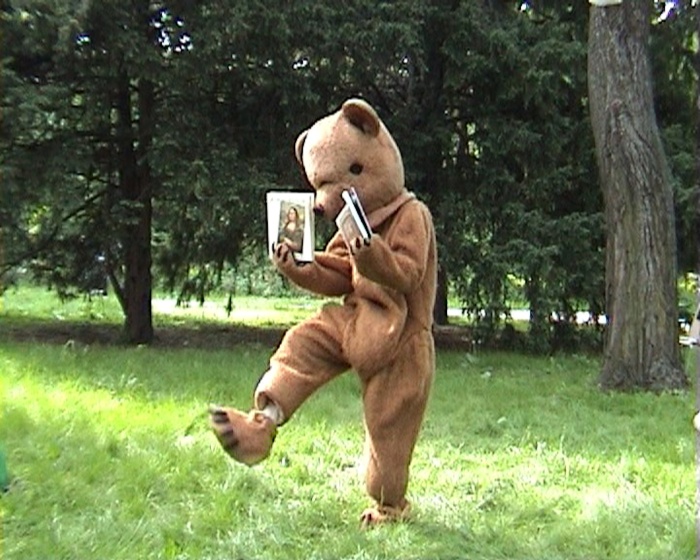

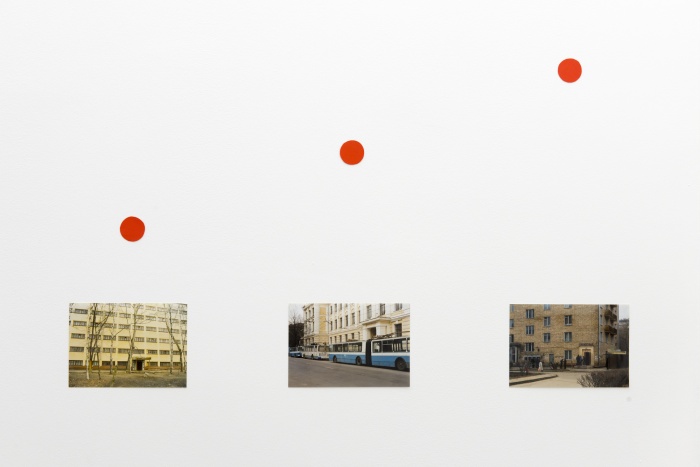

Jurij Lejderman, Miejsca, w których byłem szczęśliwy, 1995. Widok wystawy w galerii Michel Rein, 1999. Dzięki uprzejmości artisty.

Jurij Lejderman, Miejsca, w których byłem szczęśliwy, 1995. Widok wystawy w galerii Michel Rein, 1999. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

Jurij Lejderman, Miejsca, w których byłem szczęśliwy, 1995. Widok wystawy, PinchukArtCentre. Zdjęcie: Siergiej Illin, (c) PinchukArtCentre, 2015.

Jurij Lejderman, Miejsca, w których byłem szczęśliwy, 1995. Widok wystawy, PinchukArtCentre. Zdjęcie: Siergiej Illin, (c) PinchukArtCentre, 2015.

Still, we have to be aware that our memory, including “historical memory,” is not limitless. We can’t store “everything” – this would mean stopping life itself. We cannot be on all sides simultaneously, preserve all the relics, all the monuments. Because each memory and each towering monument topples different ones into oblivion – the ones that haven’t become and haven’t been erected. And the other way around, an appropriately dismantled monument (I mean, of course, the very heated debates in Ukraine today related to the “decommunization” program, but at the same time I’m emphasizing the word “appropriately” – not unthinkingly, but based on the spirit rather than the letter of the law) clears out an opportunity for a new view, new history and new memory.

In relation to this, I’m recalling my own 2015 art project called The Comrade Song,1 realized in a Kiev gallery. I mean the Soviet song The Comrade, which I loved when I was a kid. The song was about an “older comrade” who left to fight in a war, about heroism, loyalty, friendship. Clearly, today this song is perceived somewhat differently, especially since Ukraine was attacked by a country which had always presented itself as its “older comrade.” I now have a similarly ambiguous attitude to the years when I lived in Moscow, and to the “older comrades” and teachers I had there, who, in the situation of conflict, turned out to be conformist at best. So to the accompaniment of that song, I covered, painted with a dripping technique à la Jackson Pollock some enlarged photos of my life in Moscow, printed on canvas – photos of my friends, exhibitions, our friendly get-togethers… as if crossing them out of my memory. I crossed out, for instance, Ilia Kabakov, who accepted a medal from President Dmitry Medvedev’s hands, I crossed out history, but not for the sake of pure negation, but rather in order to let it continue to be History with a capital H, rather than just vicissitudes of betrayal and career. To let Ilia Kabakov continue to be a great artist and my teacher for me, but not a Russian medal holder, or to let the “Moscow conceptualism” (the art movement with which I am usually identified) continue to be an aesthetic innovation and search, rather than an official export label similar to the “Russian ballet.” In other words, I demonstrated my readiness to cross out a part of my own biography – precisely to let it remain my own biography, rather than something that “just happened so,” to let it be open to the future, to new histories and new hopes.

Jurij Lejderman, praca z projektu Pieśń „Towarzysz”, 2015. Technika mieszana. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

Jurij Lejderman, praca z projektu Pieśń „Towarzysz”, 2015. Technika mieszana. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

How connected, in your opinion, are the issues of morality, ethics and art? How necessary and how possible is it to separate your personal stance from your artistic stance?

This is actually something that the events in Ukraine have given me as an artist—an understanding of the ethical position of art, of an act. This is something that I value very much in my young Ukrainian colleagues. In the circle of the so-called “Moscow conceptualism,” where I grew up, I was taught the exact opposite – to strictly separate aesthetics from ethics, art from life. However, over time, I started to realize that art has a meaning only as truth which you can share with others, it’s sorrow over the perishability of the world, indignation at injustice, it’s rapture, fury, hope, memory. My favorite phrase belongs to the American abstractionist Robert Motherwell: “Art is a series of aesthetic decisions about ethics.” And obviously, you can say that not only about painting. But the opposite is also true; as for Moscow, for example, I feel like the a priori impossibility of an act, the internal prohibition of ethical action is the main reason behind the crisis and the aesthetic poverty in which contemporary Russian art is finding itself.

Translated from Russian by Roksolana Mashkova

BIO

Yuri Leiderman (born 1963 in Odessa, USSR) is a multidisciplinary artist and writer based in Berlin. He has participated in apartment exhibitions in Moscow and Odessa since 1982. Leiderman graduated from the Moscow D. Mendeleev Institute of Chemical Technology in 1987 (now – D. Mendeleev University of Chemical Technology of Russia). His artistic practice exists on the edges of visual arts and literature, cinema, and ethnography.

He was also one of the founding members of the Inspection Medical Hermeneutics group (together with Sergei Anufriev and Pavel Pepperstein) in 1987 until he left the group in 1990. Leiderman was awarded the Andrei Bely Prize in 2005 for his book Olor and he received the Cinema XXI Special Jury Prize at the 8th Rome Film Festival for the film Birmingham Ornament. Part 2 that he created together with Andrey Silvestrov. He has participated in numerous international exhibitions of contemporary art, including biennials in Venice (1993, 2003), Istanbul (1992), Sydney (1998), Shanghai (2004), Manifesta (Rotterdam, 1996) among others.

Tetiana Zhmurko is an art historian, researcher, lecturer, and author based in Kiev. She obtained her MA in the National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture. Throughout her professional career she has been working on different positions in the National Art Museum of Ukraine, where today she is the head of the research department of Ukrainian art of the 20th and 21st centuries. In 2018, she co-curated A Space of One’s Own exhibition at the PinchukArtCentre, and since then she works as a curator in curatorial groups including solo exhibitions of Oleg Holosiy in the Mystetskyi Arsenal in Kiev and of Myroslaw Yagoda in the National Art Museum of Ukraine. Zhmurko also works as an author writing texts on Ukrainian contemporary art collaborating with the Research Platform of the PinchukArtCentre and online magazines on art such as Your Art and BirdInFlight. She also gives lectures on Ukrainian contemporary art at the National Art Museum of Ukraine and PinchukArtCentre.

*Cover photo: Yuri Leiderman, If You Face the South, Moscow Stays Far Behind, 1983. Performance. Courtesy of the artist.

[1] The Comrade Song exhibition was held in the Vozdvizhenka Art House 32 in Kiev between November 12 and December 21, 2015.