On New Year`s Eve 2020, Korniy Hrytsiuk’s mockumentary 2020: Deserted Country1 was released online.2 This satirical dystopian film depicts Ukraine in 2020, the country being abandoned by almost all its citizens after the introduction of visa-free travel.3

In reality, the statistics on the extent of Ukrainian labor migration paints a slightly different picture. In March 2019, the Ministry of Social Policy of Ukraine, after a request by Radio Liberty, reported about 3.2 million Ukrainians working abroad on a full-time basis, and 7 to 9 million doing so for a particular period of time (i.e. seasonal jobs).4 According to various sources, Poland remains one of the most popular destinations among Ukrainian workers, offering simplified employment conditions. The influx of Ukrainian migrants after 2014 did not go unnoticed in Poland: in 2017, the rights of this new “class” of precarious workers was taken up as an agenda by Ukrainian organizations in Poland, as well as by leftist Polish organizations and cultural initiatives. The issue has also been explored by the team of The Visual Culture Research Centre,5 who were invited by Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw as curators of the tenth anniversary festival Warsaw Under Construction 2018 [Warszawa w Budowie 2018].6

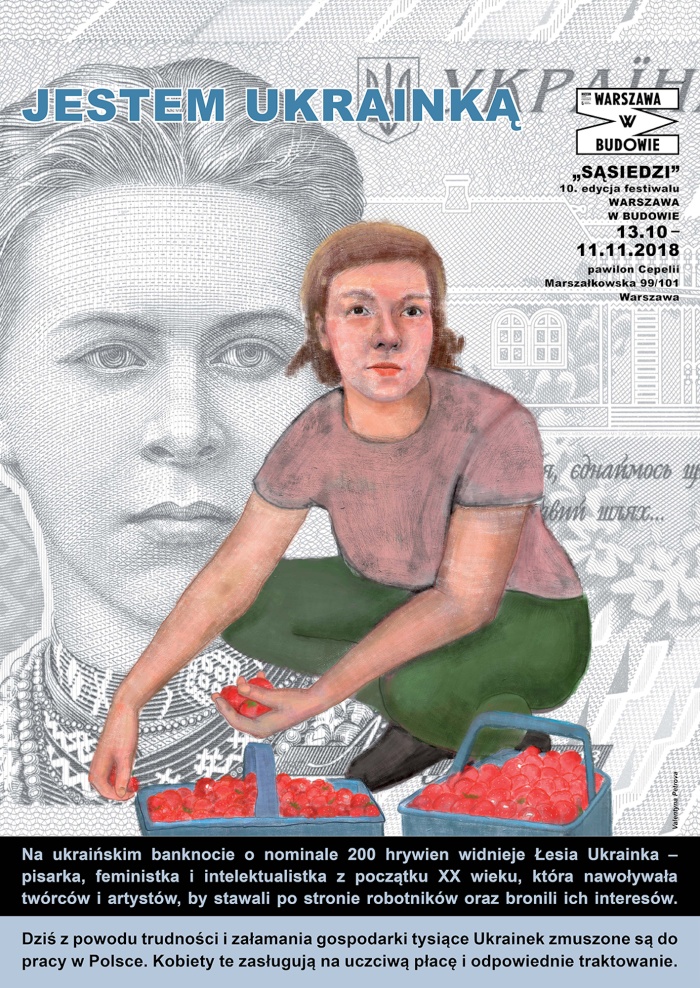

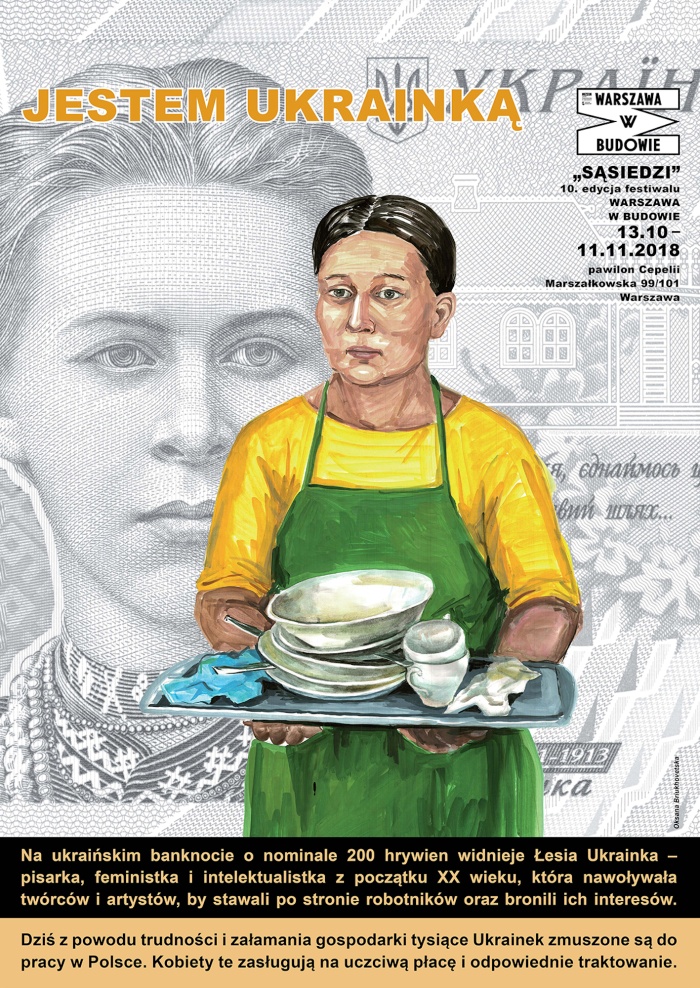

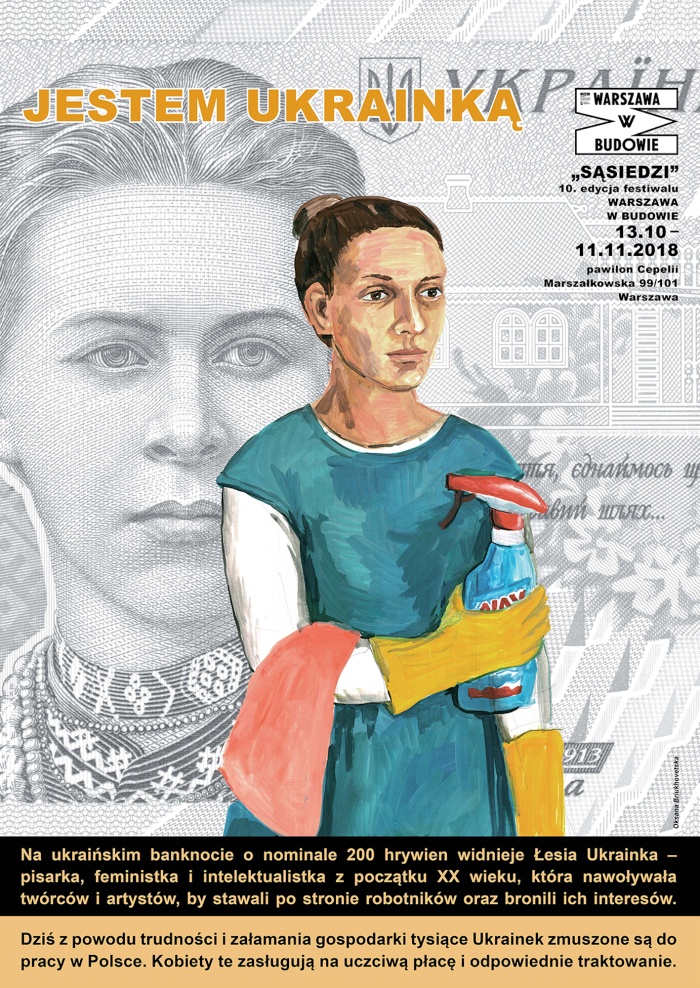

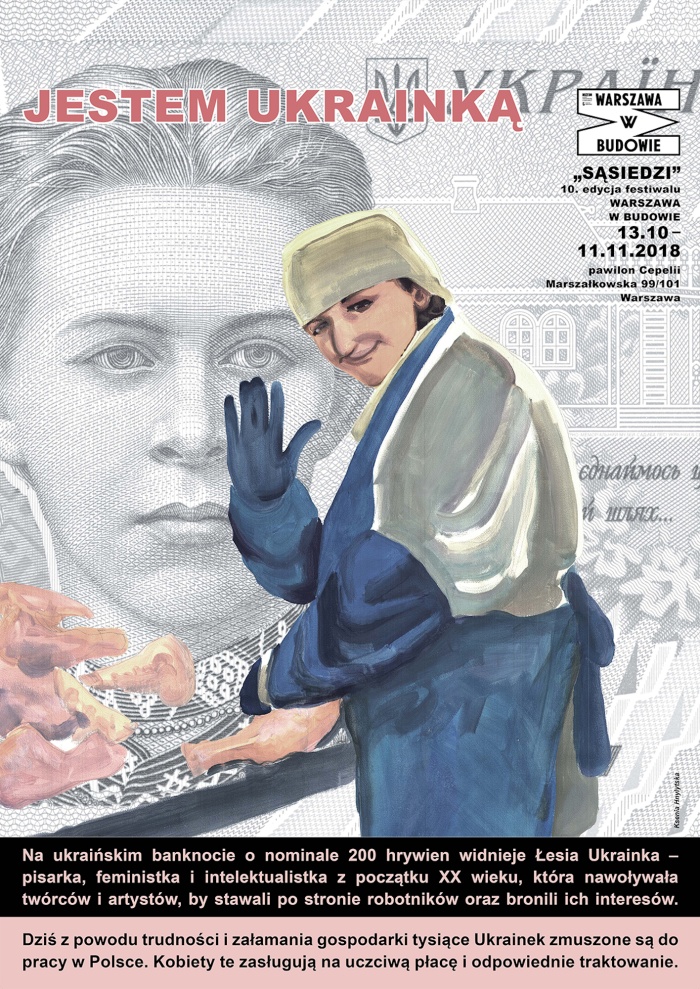

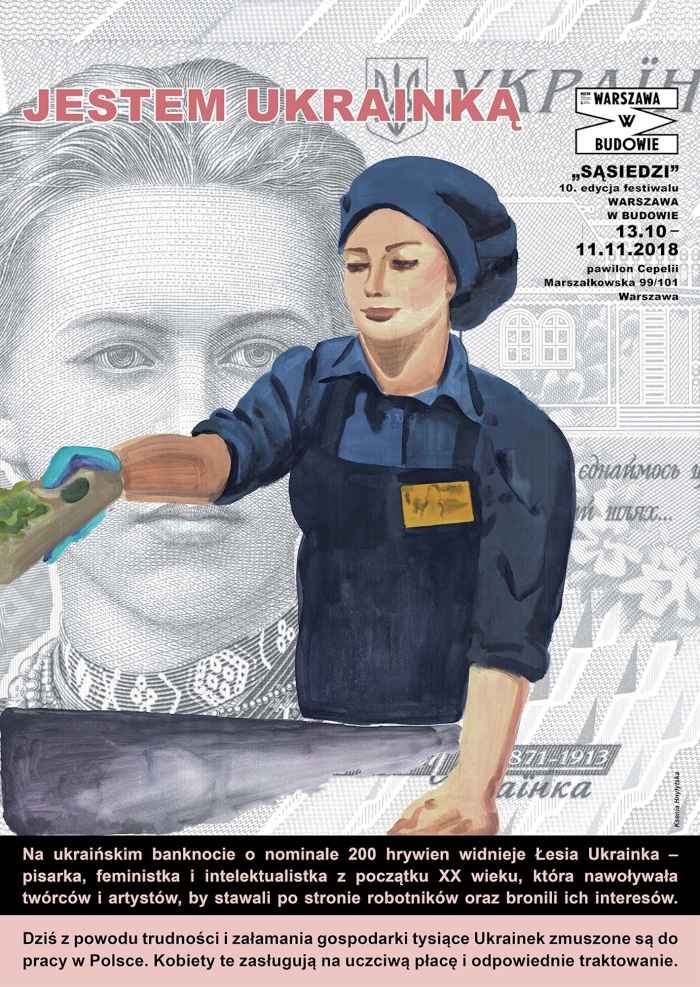

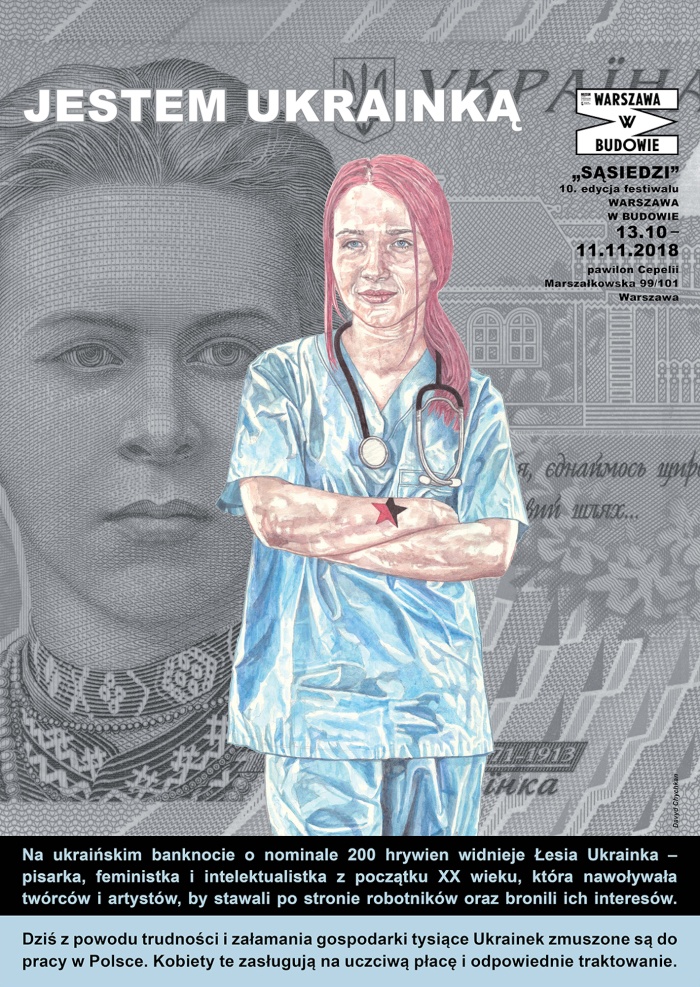

The festival was entitled Neighbors7: a simple and concise word that embodies a very heterogeneous concept, denoting coexistence and alienation, love and hatred, similarity and difference – at the level of an apartment building, a town or a city, and at the level of a state border as well. A public discussion around the festival was sparked by Oksana Briukhovetska’s art project I am Ukrainian – a series of posters based on drawings by Ksenia Hnylytska, Valentyna Petrova, Davyd Chychkan, and Oksana Briukhovetska was distributed across different parts of Warsaw. The aim of the project was to represent Ukrainian women workers who, often having higher education and supreme qualifications, are forced to take humble, invisible, and hard jobs, such as caring for people and their homes, cleaning, nursing, or working at meat processing plants. The posters portraying the women workers also had a background portrait of Lesia Ukrainka: a Ukrainian poet (1871–1913), writer, translator, intellectual, and one of the ideologists for Ukrainian socialism. Today, her face is shown on the 200 Hryvnia banknote.

Walentyna Petrowa, Zbieraczka truskawek, 2018. Plakat z serii Jestem Ukrainką (pomysłodawczyni i kuratorka serii: Oksana Briuchowecka). Dzięki uprzejmości Oksany Briuchoweckiej.

Oksana Briuchowecka, Kelnerka, 2018. Plakat z serii Jestem Ukrainką (pomysłodawczyni i kuratorka serii: Oksana Briuchowecka). Dzięki uprzejmości Oksany Briuchoweckiej.

Oksana Briuchowecka, Sprzątaczka, 2018. Plakat z serii Jestem Ukrainką (pomysłodawczyni i kuratorka serii: Oksana Briuchowecka). Dzięki uprzejmości Oksany Briuchoweckiej.

Ksenia Hnyłycka, Pracownica fermy drobiu, 2018. Plakat z serii Jestem Ukrainką (pomysłodawczyni i kuratorka serii: Oksana Briuchowecka). Dzięki uprzejmości Oksany Briuchoweckiej.

Ksenia Hnyłycka, Pracownica fast foodu, 2018. Plakat z serii Jestem Ukrainką (pomysłodawczyni i kuratorka serii: Oksana Briuchowecka). Dzięki uprzejmości Oksany Briuchoweckiej.

Dawyd Czyczkan, Pielęgniarka, 2018. Plakat z serii Jestem Ukrainką (pomysłodawczyni i kuratorka serii: Oksana Briuchowecka). Dzięki uprzejmości Oksany Briuchoweckiej.

I am Ukrainian has sparked outrage from parts of the Ukrainian community in the social media, as it was allegedly reproducing stereotypical portrayals of Ukrainian women workers; it was discussed on Ukrainian television and provoked a counter-campaign Jestem Ukrainką, jestem z tego dumna [I am Ukrainian, I am proud of that]. AndriJan Design studio created a series of posters with photos of Ukrainian women holding more prestigious jobs in Poland and boasting about their own success.

The exhibition Neighbors was the focal point of the festival, taking place at the Cepelia hall.8 Among the works on display there was a video by the TV Kryzys collective9 entitled Agencja [Agency], which came about as a rethinking of the authors’ activist experience. The project is a recording of a live conversation with recruitment agencies in Poland and the UK. In the first one the authors make a call on behalf of a businessman who is looking for cheap Ukrainian workers and declares his intention to violate the basic workers’ rights. The second is on behalf of a British employer interested in Polish workers. A comparison of the two conversations leads to the conclusion that the working conditions and status of Polish workers in Britain are similar to the conditions and status of Ukrainian workers in Poland – in both cases it is only the interests of the employer that are taken into account.

The exhibition featured Santiago Sierra’s artwork The history of Galeria Foksal told to an unemployed Ukrainian, created back in 2002. It is symbolic that even then, within the framework of his artistic practice aimed at exposing inhumane conditions and the miserly salary of labor migrants in different countries, Sierra hires a Ukrainian worker in Warsaw – as the one in the more precarious position – to listen to a lecture series on the history of a well-known Polish gallery Foksal. The artist had forced the worker to “work” a full shift at the lowest possible wage, listening to lectures steadily.

In this context, it is appropriate to recall the first works of Ukrainian artists on the subject of labor migration to Poland, authored by the R.E.P group.10 The artistic action Smuggling (2007), carried out at a border checkpoint between Ukraine and Poland, had members of the group smuggle Russian oil in hot water rubber sacks and Russian fossil gas in inflated balloons. It referred to the daily practices of small-scale Ukrainian smugglers, who live near the border and carry packs of cigarettes and hot water bottles filled with vodka or alcohol taped to on their own bodies across the border to Poland. The footage filmed during the action, depicting a mass border crossing, makes a depressing show. In 2008 the R.E.P. created an ironic video series Superproposition,11 dedicated to the employment of Ukrainian illegal workers in Poland. The artists imitated commercials that offered the services of Ukrainian workers to potential Polish employers, emphasizing such qualities as the low cost of labor, insecurity of migrants’ labor rights, and the absence of any insurance obligations.

In 2016, Ukrainian artist Taras Kamennoy also had a taste of the migrant workers’ experience while in residence at the Galeria Labirynt in Lublin as a "Gaude Polonia" scholarship recipient.12 There he created a performative project I am a Ukrainian worker, in which he noted the reaction of the Poles to him wandering the streets of Lublin, Krakow, and Warsaw and carrying a banner with the following text: "I am an Ukrainian worker, I am looking for a job, I don't speak Polish". The banner also listed the jobs he could take: “drawing, whitewashing, concreting, etc.” This list reflects Kamennoy’s real work experience – he, like many artists around the world, cannot earn a living solely based on his art. In recent years, Kamennoy has been working on construction projects in his native Kharkiv and reflects regularly on this experience in his artistic practice. The artist arranges personal exhibitions and even auctions of his own works for his colleagues directly at the construction sites where they work. In art institutions he exhibits artworks that provide an impression of life at a construction site (with the workers often living at the same place they work). Thus, Kamennoy’s works Modular Furniture (2014–2018) and Scaffolding-Dwelling (2015–2018), presented at the Neighbors exhibition, depict objects that served the builder-artist as a resting place and a tool of labor at the same time.

Taras Kamiennoj, Jestem ukraińskim robotnikiem, 2016. Dokumentacja akcji w Krakowie. Zdjęcie: Waldemar Tatarczuk. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

Taras Kamiennoj, Jestem ukraińskim robotnikiem, 2016. Dokumentacja performansu w Warszawie. Zdjęcie: Waldemar Tatarczuk. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

Taras Kamiennoj, Kozły-mieszkanie (2015-2018) i Meble modułowe (2014-2018) na wystawie Sąsiedzi. Zdjęcie: Taras Kamiennoj. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

Ksenia Marchenko, Ukrainian journalist, artist, and also a stipendiary of the Gaude Polonia, created the CtrlAltDel photo project in 2017, dedicated to the personal stories of Ukrainian migrants. Her characters came to Poland in different circumstances, but none of them had had an easy life: an engineer from Kolomyia, Volodymyr came to Poland for a three-month construction job in order to pay out a loan he had taken in Ukraine to develop his own business; Viktoria, forty years of age, had fled the war and left everything behind in Luhansk, but was able to build a new life in Warsaw and is now waiting for her documents to arrive; two large families of Crimean Tatars left occupied Crimea, and, under the lead of a 82-year-old grandmother, who had been granted refugee status, moved to the east of Poland, rented one house for everyone, started receiving the dodatek (allowance) for children and looking into work permits for the men. This individualized approach by the author brings the human dimension into the way this issue is addressed, reminding us that the “economic migrants” as a whole is comprised of individuals, each and every one of whom hopes for their own success and happiness.

In 2019, the topic of labor migration has not lost its relevance. The project Finally13 (2019) by Kharkiv-based artists Danyil Revkovsky and Andriy Rachynsky and the curator Natalia Chychasova explores the way Ukrainian workers get to the city of Gorzów in northwestern Poland: the artists joined the workers on their trip across Ukraine and Poland by bus, waiting at the border, going through inspections, meeting and talking with other passengers. The documentation of the long trip was presented in the form of a map, indicating the time spent at each stop. After arriving in Gorzow, the artists held a performance at the bus station, meeting the arrival of other Ukrainians with cookies, bottled water, and exclamations “Finally!”

Andrij Raczynski, Daniił Rewkowski, W końcu, 2019. Zdjęcie z wystawy w Centrum Sztuki MOS w Gorzowie Wielkopolskim. Foto- i wideodokumentacja performansu: Andrij Raczynski. Dzięki uprzejmości Natalii Czyczasowej.

Andrij Raczynski, Daniił Rewkowski, W końcu, 2019. Foto- i wideodokumentacja performansu: Andrij Raczynski. Dzięki uprzejmości Natalii Czyczasowej.

Andrij Raczynski, Daniił Rewkowski, W końcu, 2019. Zdjęcie z wystawy w Centrum Sztuki MOS w Gorzowie Wielkopolskim. Foto- i wideodokumentacja performansu: Andrij Raczynski. Dzięki uprzejmości Natalii Czyczasowej.

Misha Koptev, artist and “thrash” designer from Luhansk, directly joined the labor workers in Poland. After a triumphant performance at the Kyiv Biennial in 2015,14 Koptev decided not to return to LPR15 from Kyiv, obtained the status of an internally displaced person and rented a house in a village near Kyiv. In 2019, Koptev was invited by friends to earn some money at an Amazon warehouse in Poznan, where he worked for three months. In an interview with Polityczna krytyka,16 Koptev spoke in detail about his experience and the peculiarities of working as a packer at Amazon, and concluded that although his experience was not traumatic, he did not want to be a migrant worker anymore, instead he would like to go to Poland as a tourist or to present his professional activity. Theoretically, there is an opportunity, as Poland has artistic residencies and scholarships for Ukrainians. It is also worth mentioning such Polish cultural figures as Monika Szewczyk17 and Waldemar Tatarczuk,18 who have been observing and promoting Ukrainian contemporary art for many years, personally working with Ukrainian artists, regularly inviting them to participate in exhibitions and arranging their personal projects in Poland.

As a conclusion, I would like to speak about the key problem: in whichever country a person is working, it is important that their labor rights are protected and the safety of their lives and health is assured. As TV Kryzys aptly demonstrated, when it comes to employment of migrant workers, the interests of employers are always taken first – in turn, they do not lose the opportunity to abuse the precarious position of employees to increase their own income. Unfortunately, even today in Poland, after a series of scandalous cases,19 dishonest business owners still have the opportunity to employ people illegally and neglect their safety, risking the health and life of employees and demonstrating inhumane treatment.20

At the same time, the situation is obviously worse in Ukraine, as it forces people to go abroad in search of jobs: until recently, the lion’s share of the labor market was undocumented, and an official employment did not guarantee payment. Due to a lack of safety measures, masses of people are killed, especially so at mining and construction21 – and regardless of who’s in power, wages are mostly not relevant to the real subsistence minimum. At the end of 2019, the new neoliberal Minister of Economy, Tymofiy Milovanov, initiated, with the approval of the Cabinet of Ministers, an unprecedented draft bill of the Labor Law,22 which could worsen employees’ already precarious position by making them de-facto slaves of their employer. If this bill is enacted, a massive wave of economic migration from Ukraine could reach unprecedented proportions, whatever that may mean for neighboring countries. However, the bill was strongly opposed by the all-Ukrainian trade union movement, which the MPs were forced to notice – and the decision depends on the MPs’ vote.

Therefore, global labor solidarity is as timely today as it was a century ago. The fact that artists and cultural workers from Ukraine and Poland interact in a very supportive and productive way, as this article demonstrates, adds to this optimism. It is hoped that this positive experience will extend to other areas of cooperation between Poles and Ukrainians.

Translated from Ukrainian by Oles Petik

BIO

Hanna Tsyba is an independent curator, researcher, and author of texts based in Kyiv, Ukraine. She holds an MA in Cultural Studies from the National University “Kyiv-Mohyla Academy” in 2011. Tsyba’s research interests include contemporary art and politics as well as film and Soviet Studies. In 2018–2019 she held the position of a Curator and Manager of Public Programs in thePinchukArtCentre (Kyiv). She was a member of the Visual Culture Research Centre in 2008–2018. In 2018, Tsyba co-curated the 10th edition of Warsaw Under Construction festival. In 2017 she was the Head of the Press and PR department of the Kyiv International biennial, where she also curated the exhibition entitled Market that took place in Zhytniy Market in Kyiv. In 2011–2012 she worked as an art critic and editor in ArtUkraine magazine.

Cover photo: R.E.P. collective, Superproposition 2, a video still, 2008. Courtesy of the R.E.P. collective.

* Добре, як сусід близький, а перелаз низький

[1] "2020: Безлюдна країна" [2020: Deserted Country], 2018, Ukraine, 70 minutes. Directed by Korniy Hrytsiuk.

[2] Available at the online cinema takflix.com, the website’s pilot also released on the Eve of 2020.

[3] The visa-free travel regime between Ukraine and the European Union was agreed upon in June 2017. According to the agreement, a citizen with a biometric passport issued can stay in countries of the Schengen Area for up to 90 consecutive days in any 180-day period. Some Ukrainians use this opportunity to work seasonal jobs in Europe for three months.

[4] https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/news-trudovi-mihranty-z-ukrainy/30087119.html

[5] Центр візуальої культури [The Visual Culture Research Center] was created in 2008 as a platform for collaboration between academic, artistic and activist communities. The VCRC is an independent non-governmental organization engaged in publishing and exhibition activities, scientific research, public lectures, discussions, and conferences. The VCRC organized the Kyiv Biennial in 2015 (‘The School of Kyiv’), 2017 (‘The Kyiv International’), and 2019 (‘Black Cloud’). In 2011–2014 the VCRC team published a print magazine called Політична критика, which had been Krytyka Polityczna's first international publishing project.

[6] The festival (https://wwb10.artmuseum.pl/pl) was held in two cities — Warsaw and Kyiv.

[7] The name also referring to the book Neighbors by Jan Tomasz Gross, which had been used in Poland as a justification to introduce a controversial bill on the National Memory Institute (2018), which brought about a surge in anti-Semitic and anti-Ukrainian sentiments.

[8] The second floor of a post-war Modernist hall Cepela (Warsaw, 99/101 Marszałkowska Street) was converted, which is symbolic, into a gambling arcade. The hall was cleared for the exhibition.

[9] The project’s members are anarchists and co-founders of a Warsaw squat called “Syrena”. They have helped Ukrainian labor migrants – in particular, they organized industrial actions of solidarity with workers who had not been paid by their Polish employers.

[10] The Р. Е. П. [Революційний Експериментальний Простір, Revolutionary Experimental Space] was founded at the end of 2004. Members of the group include Ksenia Hnylytska, Nikita Kadan, Zhanna Kadyrova, Volodymyr Kuznietsov, Lada Nakonechna, and Lesia Khomenko.

[11] Created with the support of F.A.I.T. foundation and Zachęta – National Gallery of Art.

[12] Gaude Polonia is a scholarship program of the Minister of Culture and National Heritage of the Republic of Poland, designed for young artists from Central and Eastern Europe.

[13] Created during a short-term residence at the art center MOS in Gorzów Wielkopolski.

[14] During The School of Kyiv biennial, a performance of Misha Koptev’s Provocative Fashion Circus Wild Orchid was held: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R5UiBu9taJg.

[15] Luhansk People’s Republic is an unrecognized quasi-statehood occupying a part of Luhansk oblast.

[16] https://politkrytyka.org/2019/12/06/mysha-koptev-pryezzhajte-y-mat-ego-vjob/

[17] Curator of contemporary art, Director at Galeria Arsenał in Białystok.

[18] Curator of contemporary art, artist, Director at Galeria Labirynt in Lublin.

[19] There have been repeated reports of severe injuries or deaths of Ukrainian workers due to employers’ failure to comply with safety standards. In June 2018, Roman Kahiani, the 24-year-old brother of artist Anna Kahiani, was killed at a construction site in Poland due to a security breach: https://ciechanowinaczej.pl/artykul/tragedia-na-budowie-w/449003.

[20] Ukrainian worker left at bus stop by Polish employer after suffering stroke dies.

[21] In particular, during the reconstruction of the Central Olympic Stadium in Kyiv for Euro 2012, seven builders were killed due to safety violations (https://ntn.ua/en/products/programs/svidok/news/2011/10/24/6817) – no official data is available and information about this is still hidden. The same stadium held the 2019 debates between the presidential candidates Petro Poroshenko and Volodymyr Zelensky – none of them mentioned the killed workers.

[22] The government’s bill No. 2708 (http://w1.c1.rada.gov.ua/pls/zweb2/webproc4_1?pf3511=67833) is ought to amend the Labor Code. At the same time, another bill – No. 2681 (http://w1.c1.rada.gov.ua/pls/zweb2/webproc4_1?pf3511=67792) would effectively deprive trade unions of protecting the employees’ interests.