It’s December 28, 2019. I’m waiting for my curator’s fee, which I was supposed to receive half a month ago, and which I was promised to have received for sure two days ago. I’m thinking of ways to influence my employer. As far as I know, the most effective tool to fight for working rights is a strike — just to refuse to continue working. The suspension of work causes material losses for the employer, that’s why it works. I have to confess that in my case it is exactly my work that is “causing” material losses for my employer. Just because the non-commercial art, I’m dealing with, is more of a way of spending someone’s money than of generating income.

In November 2014, Ukrainian artist Valentyna Petrova created an artwork, Labor of a woman artist is a hobby, for the exhibition called Lockout1 dedicated to the issue of labor. Petrova produced, namely embroidered a huge red streamer by hand with the given motto: “The labor of a woman artist is a hobby. Petrova explained that the motto referred to her family comments regarding her artistic practice as a waste of time as it was not materially rewarding: “your art is just a hobby, you need to earn money,” they used to say to her. A hobby is an activity performed in one’s leisure time for pleasure after the real job (one that is paid) is done. The time- and labor- consuming embroidery technique of the artwork is, of course, the core of its statement: the artwork is the outcome of long and tiring work.

Walentyna Petrowa, Praca artystki to hobby [Labor of a woman artist is a hobby], 2014. Haft na płótnie. Dzięki uprzejmości Oksany Briuchoweckiej.

Walentyna Petrowa, Praca artystki to hobby [Labor of a woman artist is a hobby], 2014. Haft na płótnie. Dzięki uprzejmości Oksany Briuchoweckiej.

The streamer was made in the year of Maidan Revolution, which probably defined its shape. The streamer is supposed to be used for the demonstration. Yet, the revolutionary medium of demands and claims here carries the message of social consensus that the labor of the artist is not worth being materially rewarded. This absurd combination of the form and content is a bitter statement that even in a revolutionary utopia there is no room for artists’ (and curators’, I would add) working rights. Petrova’s streamer a is a symbolic monument to labor that has failed to gain market value no matter how hard and skillful it is. Or probably it is a paraphrased statement of artistic freedom.

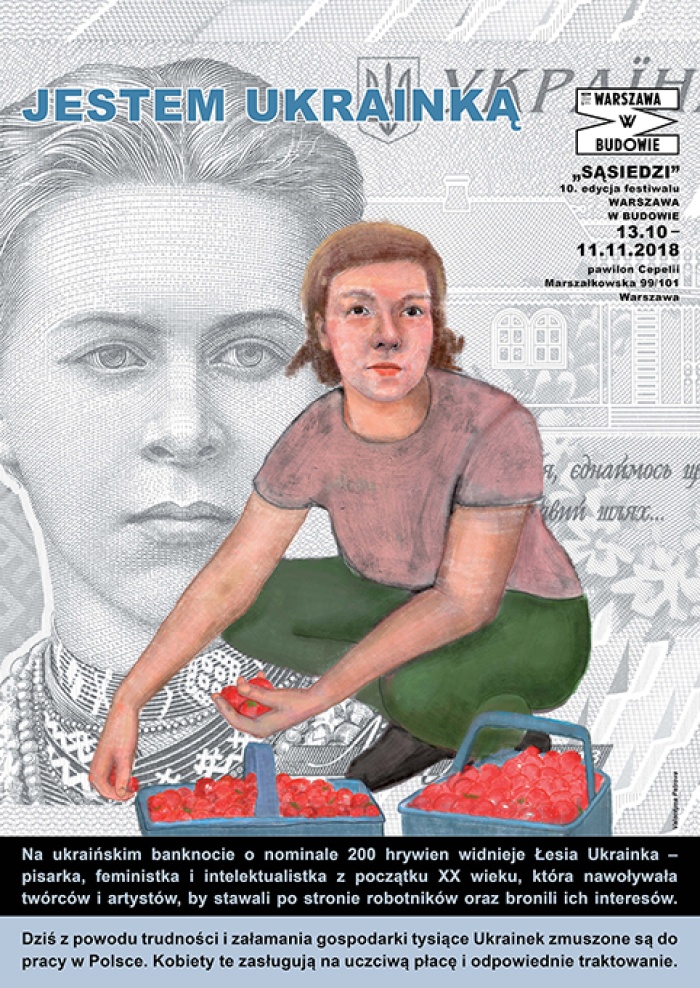

In 2018, Petrova participated in the poster campaign I am Ukrainian2 aimed to support Ukrainian female migrant workers in Poland, where she depicted herself as a strawberry collector. She drew herself just because she likes drawing self-portraits, upon the artist’s words. Indeed, she has never worked as a strawberry collector in Poland. Yet, as a representative of one of the most precarious social groups in Ukraine, the artists, she is definitely among the potential contenders for the role she depicted. While a hundred years ago, Ukrainian poet Lesia Ukrainka,3 called artists to stand on the side of the workers and defend their interests, contemporary Ukrainian artists often practically occupy the position of workers, forced to do various physical jobs beside or inside the artistic careers to sustain their living, and is exactly the group potentially disposed to labor migration.

One year later after the poster campaign Petrova wrote an article which started with the following: “Going to work in Poland — this phrase has been familiar to me since childhood. It has become a commonplace a long time ago. No matter where I was, whatever company I belonged to, there were always people nearby who or whose relatives lived partly or completely due to low-skilled work abroad, and I myself was offered a couple of times to go around abroad to make money. The environment that I now define as the place of my professional activity — the bohemian world of contemporary Ukrainian art — also turned out to be a place where you can find not just the art projects on the topic of migrant work, but also a real case of direct physical displacement to a neighboring country in order to get to earn several zloty.”4

Walentyna Petrowa. Autoportret artystki z Łesią Ukrainką w tle. Plakat w ramach kampanii "Jestem Ukrainką", 2018. Dzięki uprzejmośći oksany Briuchoweckiej.

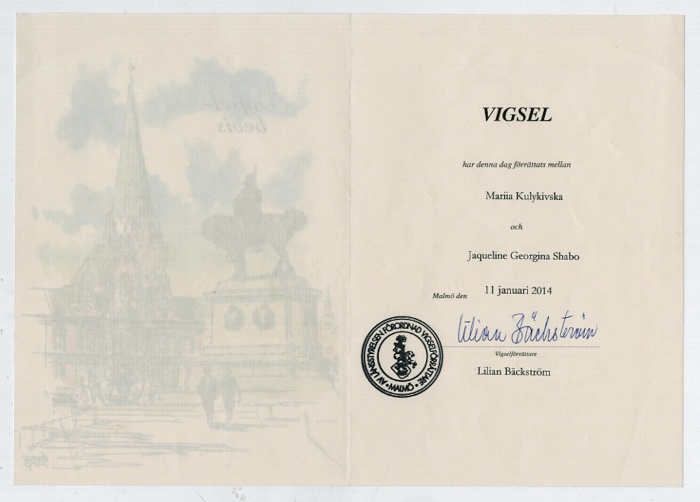

The same year as Petrova created her streamer about the precariousness of the artist, another Ukrainian artist Maria Kulikovska started “log-term performance, happening, life-experiment, an act of solidarity, artists statement and a manifesto of sisterhood/love”5 called Body and Borders. During her stay at the art residency in Sweden she officially married Swedish female artist Jaqueline Shabo.

Maria is originally from Crimea, and she performed the “life experiment” exactly after the annexation of the peninsula. She lost her home and found herself in the situation of a displaced person.

Through this marriage, the artists created same-sex family which was, as they claim, simultaneously legal in the “First-world country Sweden and illegal in the Third-world country Ukraine.” This legal ambiguity of the performed family pointed to the fact that human rights are distributed differently according to the nationality. At the same time, an officially registered marriage created the possibility for a displaced person from the Third world country such as Maria Kulikovska in this case, to obtain residency in Sweden.

The desire of Ukrainian society to become a part of European community was among the crucial driving forces of the Maidan Revolution. Against this background the performance of Kulikovska can be read as her personal implementation of the revolutionary dream. Applying the European values of sexual freedom upon her personal experience and literally performing it in her “lesbian marriage” (being herself heterosexual),6 she gets her personal permit to the European Union and its opportunities.

Akt małżeństwa Marii Kulikowskiej i Jaqueline Shabo. Dzięki uprzejmości Marii Kulikowskiej.

Maria Kulikowska, Jaqueline Shabo, Body and Borders [Ciało i granice], 2014. Dokumentacja fotograficzna performansu. Dzięki uprzejmości Marii Kulikowskiej.

Indeed, in three months after the marriage-performance Kulikovska did get the Swedish residence permit. The artist asserts that she obtained permission with an extremely short validation date because it was a homosexual marriage (in the case of heterosexual marriages the waiting time for authorization lasts over two years or more and the negative response is recurrent in the cases of non-European citizens). Staged as a promotion of sexual freedom and achievements of European democracy for a Ukrainian audience, the performance by Maria, at the same time, was quite a pragmatic case study of the possibilities of migration.

After receiving the residency permit Kulikovska moved to Sweden to work on collaborative art projects with her “artist-wife.” And, in order to pay her way in a prosperous European country, she started to work as a dishwasher in a nightclub. This artistic gesture created a legal opportunity for the labor migration of the artist.

What strikes me in the Body and Borders performance is that the life of the artist cannot be discerned here from the artistic action. What is at play is exactly the social existence of the person Maria Kulikovska with her set of identities, possibilities she has, and the limits she faces. She performs at the intersection between art and social reality, explicitly manifesting that her artistic strategy cannot be separated from the survival strategy of the artist as a precarious human immersed in a concrete social reality, left alone with her burning everyday needs.

Ukrainian artist Iryna Kudria reveals the same approach. During 2014–2015 she worked as a cleaner to earn money. She documented her work and later presented the video documentation of it as an artwork. Called Untitled (2014–2015), the artwork consists of two screens with the same videos on them — Iryna cleaning an office — yet with two different captions. One video was captioned as an artwork by Iryna Kudria, the artist, while the other as a job performed by Iryna Kudria, the cleaner. The work by Iryna Kudria clearly shows, there is no real difference between the way Iryna Kudria as an artist operates and the way Iryna Kudria as a cleaner operates; it is exactly the same.

Irina Kudria, Untitled [Beztytuł], kadr z filmu, 2014-2015. Dzięki uprzejmości artistki.

The artistic collective Shvemy (Anna Tereshkina, Maria Lukyanova, Tonya Melnyk, and Olesya Panova) implements a similar strategy, sharing their identities of being artists and a sewing cooperative at the same time. They sew for money in order to sustain their own artistic and activist sewing projects. Sometimes they sew for money to support artistic institutions. In 2017, they performed 12-hour working day at the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art (Moscow). During the performance they recreated conditions as close as possible to the real working conditions of women in third-world garment factories: a twelve-hour working day with a fifteen-minute snack break, a tight room, monotonous work, three toilet breaks, and the conversations limited exclusively to production issues. In the end, the participants sold their products with the words “Made in slavery.” For the physical bodies of the artists the performance 12-hour working day was a real exhausting 12-hour working day. Yet, compared to the working day of the women in third-world garment factories it was lived publicly, making the exhaustion of the workers visible.

Grupa Szwemy, Dwunastogodzinny dzień pracy, performans, 2017. Dzięki uprzejmości artystek.

The same year at the ART Monte Carlo fair in Monaco artist Zhanna Kadyrova presented her work Market. In this work she reproduces a typical food-selling spot, where she was selling her sculptural pieces as food items made of ceramic tiles, cement, concrete, and natural stone. In Monte Carlo the artist sold her works by weight according to the price tag 1 gram = 1 euro, dispelling the mystery of art. After ART Monte Carlo the project traveled to numerous art fairs in different countries. The price per gram always equals one of the local country’s monetary, where the performance Market is being shown. Dressed as a saleswoman Kadyrova sells her artworks from the Market spot at art fairs7 making explicit the market reality behind artistic practice — the flip side of art — which is usually shyly (or hypocritically) edged out from the impeccable gallery rooms. The link to the local currency points to the inequality embedded in it. To survive the artist needs to sell her works; the richer the country she sells in, the more money she gets, the more chances there are of maintaining her practice and her living.

Żanna Kadyrowa, Market [Targ], 2017. Fotograficzna dokumentacja performansu. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

The images of all the above-mentioned artworks could have easily become source material for the poster campaign I am Ukrainian. What we see in these works are the artists in the position of the most precarious social group, performing the task of staying afloat. The major artistic component in the performed “survival” tasks are the people who proclaim themselves artists, and on this premise expose their “dirty” job to the public.

There are so many decorations at hand produced by creative industries of late capitalism to nicely cover the real economic reality of exploitation. The public territory of art might be, instead, a space of disillusionment and exposure of the true conditions that define our lives. In case there is someone courageous enough to disclose honestly his or her true means of survival in today’s imperfect and precarious world.

Regarding my own situation as an unpaid curator I’m thinking: can this gesture of exposure have the same power as striking?

BIO

Lesia Kulchynska is an independent Kyiv-based curator, art critic, culture studies, and visual culture researcher. She worked as a researcher and curator at the Visual Culture Research Center in Kyiv (2011–2019). She is also a founder of Nomadic School of Visual Education and co-founder (together with artist Maria Kulikovska) of School for Political Performance. She curated and co-curated the following projects: Ukrainian Body (2012), discussion platform Between Revolution and War (2014), exhibition and research project Some Say You Can Find Happiness There (2015), The School of the Lonesome program of The School of Kyiv – Kyiv Biennial 2015, as well as the performance and exhibition project The Raft CrimeA (2016).

*Cover photo: Iryna Kudria, Untitled, 2014-2015. A still from a video. Courtesy of the artist.

[1] Curated by Oksana Briukhovetska at the Visual Culture Research Center, Kyiv.

[2] Initiated by Oksana Briukhovetska.

[3] At the bottom of each poster of the I am Ukrainian campaign there was a text: “On the Ukrainian banknote with the nominal value of 200 hryvnia, there is Lesia Ukrainka — writer, feminist and intellectual from the early twentieth century, who called creators and artists to stand on the side of the workers and defend their interests. Today, because of the harsh economic conditions, thousands of Ukrainians are forced to work in Poland. These women deserve decent wages and decent attitude.”

[4] https://politkrytyka.org/2019/12/06/mysha-koptev-pryezzhajte-y-mat-ego-vjob/

[5] https://www.mariakulikovska.net/en/body-and-borders-wedding

[6] For now, Maria is already divorced with Jacqueline and has married to a man.

[7] https://www.kadyrova.com/market-2017?lightbox=dataItem-jrajp54i2

https://www.kadyrova.com/market-2017?lightbox=dataItem-jlgcp34f