This essay addresses the representation of Africa in Poland, focusing especially on exhibitions and cultural institutions within Warsaw’s art and culture ecosystem. Two primary questions weave through the essay. Specifically, how do exhibitions and cultural institutions represent various dimensions of the relationship between Africa and Poland including the subjects of Africa in Poland, Africans in Warsaw, and Poles in Africa? What can we glean about the role of cultural and artistic projects in constructing and mediating knowledge about the continent of Africa in the city of Warsaw? Drawing upon research undertaken during my residency at the Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw in September 2019, this essay is informed by visits to several institutions and conversations with more than a dozen individuals who shared their views on the portrayal of the continent in the city.

With an estimated few hundred Africans in Warsaw, this capital city presents a very different diasporic scene than the better-known examples of Paris or London where many Africans from former French and British colonies reside. Unlike the British or French, the Poles had no colonies in Africa. The colonial histories and post-colonial conditions that shape African diasporic contexts in Paris or London do not carry over to Warsaw. While Warsaw does have other diasporic populations unified by language, history, politics, and religion, they represent a relatively small minority and African immigrants do not figure as numerously in Warsaw as Vietnamese, Ukrainians or Belarussians. At first glance, and in striking contrast to London or Paris, there was little discernable African presence on the streets, public transportation, or in shops. For most Africans who reside in Warsaw, immigration was motivated by opportunities for higher education and access to the broader context of cities in the European Union. My conversation with migration studies scholar Aleksandra Winiarska pointed out that Poland is less a destination in itself for African immigration than a springboard for mobility to western Europe.

Even without a robust African presence, the question of where and how Africa, Africans, and African culture are represented in Warsaw has many answers. I was surprised to learn that two Africans have served in Poland’s Parliament and less surprised to hear that Africans play on the Polish national soccer team. Other sites for making Africa visible in Warsaw include the media, public museums, private galleries, the university, and a film festival call Afrikamera now in its 12th edition, to name a few. These institutional spaces related to art and culture are powerful sites for the representation of Africa and Africans in Warsaw. Their capacity to advance or challenge narratives and to shape popular perception is worth underscoring. In Warsaw’s art and culture ecosystem on the whole, two dominant narratives coalesce – one constructs difference and one deconstructs it. The construction of difference – the Othering – that accompanies some representations of Africa and Africans in Warsaw can be read within the frame of racial and religious homogeneity characterizing Poland in 2019 as well as by current politics and complicated histories of empires, divisions, migrations, destruction, rebuilding, independence, centuries of cosmopolitanism, and decades of nationalism.

The National Museum of Ethnography in Warsaw is a somewhat expected institution for the representation of Africa. During my visit, a selection of the museum’s Africa collection was featured in an exhibition entitled, Magic Technology. The exhibition encompassed mostly wooden masks and sculptures used for divination, fertility, initiation, hunting and so on. These objects were displayed alongside various tools and implements on podiums in the gallery space. The selection of art objects aligned with well-known object types; however, the desired outcome of pairing art objects with tools and implements defied explanation. Why for instance, would a Bamana Chi Wara headdress share a podium with a metal wrench? Why would a Makonde mask be displayed alongside a metal clamp? Although this exhibition might have been an opportunity to engage in deconstructing difference, its theme and display reinforced stereotypes originating in 19th-century binaries of science versus magic and religion versus ritual. (Figure 1-2)

Il. 2

Il. 1

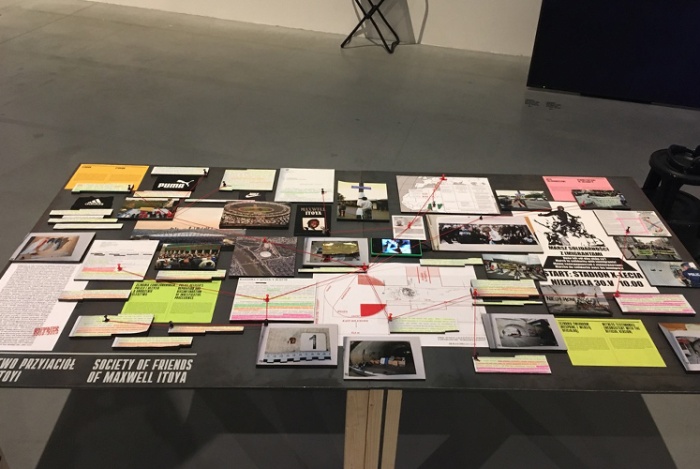

Another example was The Modern Art Museum on the Vistula’s exhibition entitled, Never Again: Art Against War and Fascism in the 20th and 21st Centuries. In the rectangular space filled with paintings was a table displaying archival documents about the death of Nigerian merchant Maxwell Itoya who sold his wares at the informal market at the soccer stadium in Warsaw’s Praga District. Itoya was killed on 23 May 2010 during a confrontation with police in the market. With conflicting accounts about the events preceding the shooting, Itoya’s death prompted public protest about racism and police brutality. The museum’s display was composed of photographs, documents, maps, and other images connected by red yarn. Its effect was to suggest linkages among people and stories while evoking an interpretation about Itoya’s death. As much as this exhibition was a compelling proposition in light of the national elections in October 2019 and larger political concerns globally, the display about Itoya offered necessary contextualization about his death as well as the population of African merchants who sold their wares at the soccer stadium from 2008 to 2010. (Figure 3)

Il. 3

During Warsaw Gallery Weekend in September, Propaganda Gallery featured an exhibition entitled, Tropical Craze, a mixed-media show incorporating the work of named and anonymous artists. The gallery space included two-dimensional and three-dimensional works. There were photographs including one marked by the phrase “Europeans Only,” display cases presenting objects of African material culture such as statuettes, renderings of weapons, and sculptures. The narrative advanced by the objects in the show was ambiguous, at once constructing and deconstructing The Other. The show seemed to both consolidate and question primitivist inscriptions about Africa and Africans while sparking reflection about race and the exclusionary politics for boundary crossing in migration and art world representation. (Figure 4–5)

Il. 5

Il. 4

Stretching beyond Warsaw’s art and culture ecosystem is The Razem Pamoja Foundation, a NGO based in Kraków. Comprised of a publishing house, an art gallery, and a store, the foundation offers a somewhat more complex and collaborative point of view on the relationship between Africa and Poland. Pamoja Foundation supports socially engaged art projects linking Polish artists to other parts of the world, including Africa. Per my conversation with activist artist Lukasz Roth who has participated in projects in Kenya and Indonesia, the foundation is a platform for collaborative solution design by way of socially engaged art projects. At the time of my visit, backpacks fabricated from African cloth by youth in Nairobi were displayed for sale in the foundation’s gallery. Like other displays and exhibitions focusing on material culture referencing Africa, this one indicates the ease with which objects move across borders. On the other hand, the movement of people across borders is complicated by the politics of migration, access to resources, and the networks created by diasporic populations. (Figure 6-7)

Il. 7

Il. 6

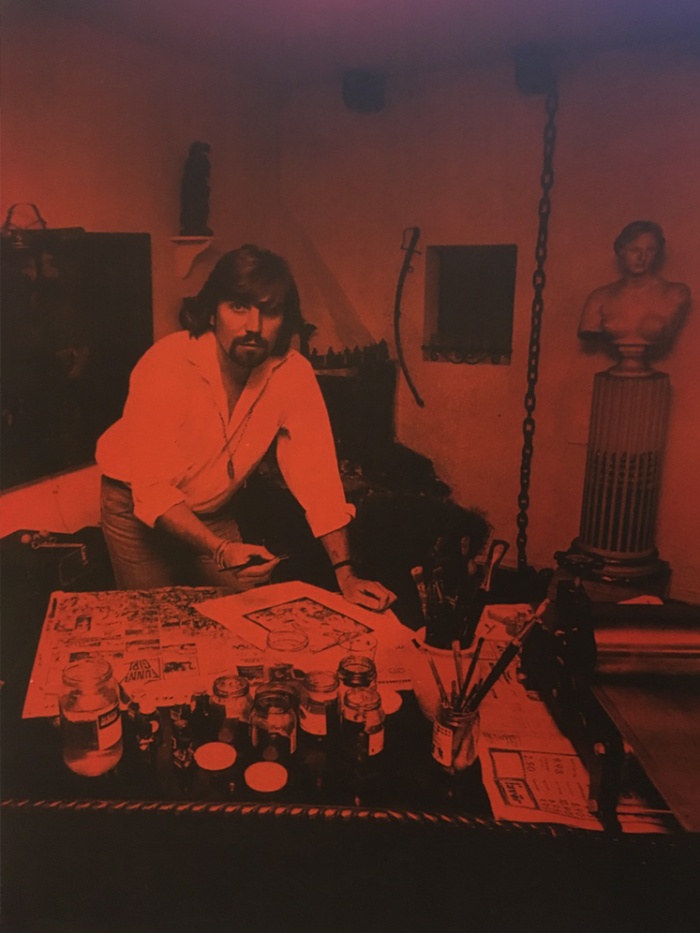

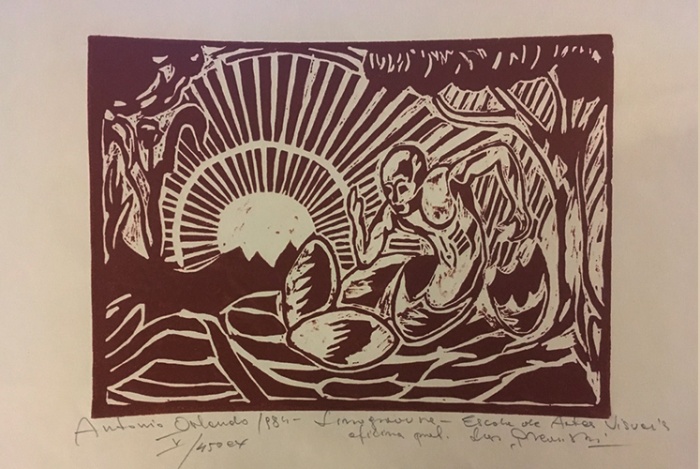

Another dimension of the relationship between Africa and Poland is the long history of Poles in Africa and especially in eastern Africa in the 20th century. While Poland had no colonies in Africa, it was involved in diplomatic and development projects in several African countries in the pre- and post- independence eras. Of particular interest to this inquiry is the work of artist Lech Rzewuski in founding the Escola de artes visuais in Maputo. Rzewuski attended the Art Academy in Wrocław and lived for many years as a professional artist in Sweden. It was after visiting his brother, Professor Eugeniusz Rzewuski who was based in Mozambique, that he moved to Maputo where he worked from 1981 to 1986. Lech was the founding artist-teacher at the Escola de artes visuais along with other expatriate artists from Cuba, Chile, and Georgia. Bringing his own supplies and equipment, Lech, together with Malangatana Valente Ngwenya, considered the father of modern Mozambican art, taught graphic arts to numerous students at the school. The role of European expatriate artists in establishing art schools in Africa is well-known in the history of modern African arts – Ulli Beier in Nigeria, Pierre Lods in Congo and Senegal, and Frank McEwen in Zimbabwe. To this history, we can add Lech Rzewuski in Mozambique. Even after his departure from Maputo, the influence of place on his practice was legible as exemplified in the work, African Dances (1987). (Figure 8–10)

Il. 9. Lech Rzewuski

Il. 10. Lech Rzewuski, Afrykańskie tańce.

Il. 8. Praca wykonana w pracowni Lecha Rzewuskiego w Escola de Artes Visuais.

Of the individuals and institutions in Warsaw’s art and culture ecosystem, a few stand out for their work to undo the Othering that characterizes some projects representing Africa. These underscore the power of art and culture to expand the boundaries of the continent’s representation in the city. Mamadou Diouf, a Polish musician and writer originally from Senegal, hosts a well-known radio show, heads an NGO dedicated to promoting understanding about Africa, and has authored the books A Little Book about Racism and How to Talk to Polish Children about Children from Africa. Another advocate for the understanding of African culture, dancer Dúnia Pacheco, originally from Angola, is well-known for her work teaching and promoting African dance and culture in Warsaw. Conversations with Diouf and Pacheco offered many insights about the specificity of Warsaw and Poland more broadly for African residents. Both have been settled in Warsaw for decades – Diouf arrived in 1983 and Pacheco in 1999. Both speak Polish fluently, have expertise in Poland’s history and culture, and have family in Poland. These critical elements to making a home away from home also bolster their authority to the describe the range of experiences associated with being African in Poland, from curiosity to racism, and from misinformation to goodwill (Figure 11–12).

Il. 11. Mamadou Diouf

Il. 12. Dúnia Pacheco. Zdjęcie: Violetta Wącierz.

While the exhibition, At First I Thought I was Dancing, at the Ujazdowski Castle took place in 2016, it prompted my first reflections on Africa, Africans, and African art in Poland. It remains a shining example of art’s successful deployment to undo constructions of difference and exoticism by resituating Africa as contemporary and global. Featuring the work of Senegalese artist El Sy, this was the first exhibition focused on a contemporary African artist in Poland. The show shifted the discourse from Africa as The Other in monocultural Poland to a more inclusive representation of Africa as integral to contemporary global art. Focused on the performative and socially engaged dimensions of Sy’s practice, the exhibition was very much in keeping with the Castle’s mission to be experimental and was a strong example of the need for an art institution in Warsaw to lead paradigm shifts about inclusion and art world globalization. (Figure 13–16)

Il. 16. Widok wystawy. El Hadji Sy, "Na początku myślałem, że tańczę", (c) Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej Zamek Ujazdowski, Warszawa, 16.06 – 16.10.2016. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka.

Il. 15. Widok wystawy. El Hadji Sy, "Na początku myślałem, że tańczę", (c) Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej Zamek Ujazdowski, Warszawa, 16.06 – 16.10.2016. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka.

Il. 14. Widok wystawy. El Hadji Sy, "Na początku myślałem, że tańczę", (c) Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej Zamek Ujazdowski, Warszawa, 16.06 – 16.10.2016. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka.

Il. 13. Widok wystawy. El Hadji Sy, "Na początku myślałem, że tańczę", (c) Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej Zamek Ujazdowski, Warszawa, 16.06 – 16.10.2016. Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka.

BIO

Joanna Grabski is an art historian whose research focuses on artists, art institutions, urban life, and art world globalization. She is currently Director of the School of Art and Professor of Art History at Arizona State University. Her book, Art World City: The Creative Economy of Artists and Urban Life in Dakar, is the product of seventeen years of research with artists, collectors, and art world mediators in Dakar, Senegal (IU Press, 2017). She is also co-editor of African Art, Interviews, Narratives: Bodies of Knowledge at Work (IU Press, 2013) and guest editor for a special issue of Africa Today dedicated to “Visual Experience in Urban Africa” (2007). Her essays on artists, urban creative expression, and visual life in Dakar have been featured in several edited collections and journals, including Art Journal, African Arts, Fashion Theory, Nka, Présence Francophone, and Social Dynamics. In 2012, she wrote, directed, and produced the feature length documentary film, Market Imaginary (distributed by Indiana University Press), focused on Dakar’s sprawling Colobane market, famous as a crossroads for secondhand clothing, shoes, and electronics.

* Cover photo: El Hadji Sy, "At first I thought I was dancing" exhibition. (c) Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, Warsaw, 16.06 – 16.10.2016. Photo: Bartosz Górka.