Role Playing in the Post-Truth Era

Post-truth is the international word of the year for 20161 as announced by the Oxford Dictionary, which annually picks a word that reflects the ethos of our current times. According to its definition, post-truth relates to circumstances in which “objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.”2

Apparently the usage of the term has increased by 2000% in the past year, with spikes reached during the UK Brexit referendum, the US Presidential campaign, and their outcomes. These socio-political events have weighed heavily on the global discourse that poses questions related to the influence that the narrations orchestrated in virtual “spaces” have on our global politics and relationship with ruling powers. The issue has been address by the US media in their apologetic response to the failing of polling machines, by Chinese President Xi Jinping3 during the Wuzhen Internet International Convention, and most recently by Italian Prime Minister Renzi who mentioned post-truth in the resignation speech he delivered after the results of the constitutional referendum.4

The global tendency of pointing fingers against the impact of our virtual life on our physical existence makes us wonder whether we can still discern where the dividing line between the two stands. The effects of mythologies engendered online and digital tribalism on the current perception of ruling institutions are taking a central role in what we may label as technological anxiety.

Let alone the impact that the coexistence of our online and offline lifestyles has on a more individual scale, on the construction of our own identity in the age of digital self-promotion and projection. The narratives of our lives are shaped in real time, by posting reposting, and pinning on digital interfaces in a cunning game to be won with the accumulation and constant nurturing of followers and positive feedback.

As social media apps are setting new sets of rules for our interaction with other users and with the reality that surrounds us, they increasingly morph replicating dynamics that remind one of a MMORPG (Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Game), though our virtual counterparts are not digital avatars anymore but our own image at its best angle, occasionally mediated by beauty filters.

MMORPG are changing too, with a tendency of mimicking reality through games that provide alternative worlds free of restrictions, where players can live ordinary lives where failure, laws, and death can be escaped with virtually infinite chances of rebound.

East Asia as a techno-imaginative geography

Technological anxiety has obviously taken a central role in the practice of a large number of visual artists operating in different decades and geographies, questioning the points of contact and diversion of our virtual and digital selves to pin down different aspects of the human condition in our tech-driven era.

When it comes to the imagery connected to technological anxiety and its aesthetic developments throughout the past three decades, it is interesting to note how the discourse has been woven into the representation of East Asia.

It is widely known that there are Western anxieties towards the Japanese supremacy on global technological production, which gave birth in the ‘80s to a series of stereotyped representations that were applied to the broader imaginative geography usually labelled as “East Asia.” When the concept of techno-orientalism was first introduced by David Morley and Kevin Robins in 1995,5 it referred to these representations, dystopic depictions of Japan as a reality where individuals were obsessed with technology and even dehumanised by it.

Twenty years after we might wonder whether these western constructed imagery of East Asia as the tech-other have influenced East Asian artists’ representation of the relationship between cultural and individual identity, the self, and technology. When we talk about identity formation and self-representation, one of the most cited quotes, usually in regard to African diaspora, is the seminal concept of double-consciousness advanced in 1903 by Du Bois, which refers to how being represented as the other influences one’s self-representation, the “sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others.”6 In the same way it can be argued that the cultural representation and self-projection of Asian artists is constructed by quoting existing archetypes produced by Euro-American society, through their transformation and subversion.

In this sense, several scholars have explored how Japan embraced in the past decades a process of self-orientalization that, through the construction of new representational sets, started shifting techno-phobia into techno-philia, conferring positive interpretations on to the negative stereotypes that western global entertainment and sci-fi literature had hegemonically established on a global scale.7

The self-orientalism employed by Japan became, in fact, a fundamental engine of growth that boosted the country’s economy after the ‘90s recession, through the development of a cultural branding and soft-power strategy based on the export of youth culture and related products.

This process of cultural export and the ever-increasing fandom for Japanese pop culture have also boosted the circulation of techno-orientalist imagery that transcend Japanese identity to subsume all of East Asia into a single universalizing entity.8 Hence, if recent Japanese identity is in large part constructed through the global projection and reception of various forms of its popular culture, can we detect the references and effects of its visual imagery in contemporary art produced within and outside of Japan?

We are going to consider here the work of three artists rooted in their cultural milieu though operating with a global projection, in the international art arena. The practice of Mariko Mori, Lu Yang, and Korakrit Arunanondchai, born in three different decades – respectively in the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s – share concerns over issues related to techno-humanism and cultural representation.

There are several reasons why the work of globally renowned Japanese artist Mariko Mori is often mentioned in relation to techno-orientalism, one of them being the resonance of the abovementioned dynamics that link Japan’s stereotyping subsequent self-representation, and technology.

In her early practice the artist’s performative body was an integral part of the work. In the series of photographs she realised in 1994, in Tokyo, Mori incarnated cyborg beauties, digital gaming avatars, manga characters dressed in silvery garments, shiny armor, and pointy ears. It is difficult to determine where the boundaries between self-orientalization and genuine representation of Japanese pop culture stand in this series.

While referencing globally popular Japanese youth culture trends, especially that of adolescent girls, Mori was at the same time questioning deeper issues linked to the categorization of female roles and their relationship to anime cyborg phantasies. This series seems to be the by-product of a negotiation between Mori’s cultural identity and its transnational representations.9

In the context of this duplicity and tension between the local and global, real and projected, it is not surprising that the term “cosplay” – an exported Japanese trend – coined by Nobuyuki Takahashi of Studio Hard at the 1984 World Science Fiction Convention in Los Angeles, borrows two English words to determine its own Japanese etymology.

The developments of the shifting identities of Mori’s avatars and idols by the end of the ‘90s are particularly fascinating. In the Esoteric Cosmos series, her characters had entered a techno-spiritual sphere, with her appearing in shamanic roles, and featuring elements from Shintoism and Buddhism, incorporating traditional iconography while experimenting with 3D technology, digital animation, and multisensory installations. The relationship between the past and cultural heritage is extensively present in Mori’s oeuvre, most notably in Beginning of the End: Past, Present, Future (1995–2006), a photographic cycle produced over a period of eleven years, in which Mori presents herself as a time traveler in a Plexiglas capsule at significant symbolic locations, from Giza, to New York, to Shanghai. For the artist, technology is a tool that allows us to reconnect with our past.

In the following years, as Mori’s practice started to increasingly focus on the relationship between humans and nature, and the merging of the two into one entity, the body of the artist began to disappear from the work. Drawing from the Buddhist concept of the world existing as one interconnected organism, in 2003, she presented Oneness, a sculpture of six alien figures in a circle linking hands. As visitors kneeled and hugged the aliens, their eyes would light up and their heart started beating. The work was both an allegory of connectedness, of the disappearance of boundaries between the self and others, and acceptance of alterity, transcending national and cultural borders.

Echoing spiritual concepts as well as the era of digital connectedness, Mori’s idea of a universal oneness links the material, spiritual, and technological spheres. In 2010 she founded the Faou’s Foundation, an organization aimed at the creation of site-specific installations placed in six unique ecological settings, each one located in one of the earth’s six habitable continents. The most recent, Ring: One with Nature is a luminous 6 meter-high ring installed at the peak of a Brazilian waterfall to mark the Rio Olympic Games.

As Mori has been shifting her focus on nature, though combining it with futuristic and outer space aesthetics, it is interesting to notice how the elements considered in her practice – techno-spirituality, performing body, cultural and individual representation – are visually and conceptually rendered in the work of artists of later generations.

Born in China in 1979, Lu Yang mixes biomechanics, Japanese visual pop-culture, Buddhist iconography, avatars, and superheroes in her work. Like Mori, Lu Yang addresses feelings of connectedness, in her case more directly linked to our existence on the Internet, where “you can abandon your identity, nationality, gender, even your existence as a human being.”10 Japanese cartoons – aired by many television channels during Lu Yang’s childhood in Shanghai – along with sci-fi movies and computer-generated effects and gaming, have significantly influenced her works.

Her 2013 animation Uterus Man was initially inspired by Mao Sugiyama, a Japanese performance artist and activist who infamously had his genitals and nipples surgically removed to promote asexuality and gender equality, and later served them at a banquet in Tokyo. The aesthetic choices for this work are largely taken from manga visuals, where Uterus Man is a sci-fi super-hero whose powers derive from him being the anthropomorphic embodiment of a Uterus. As he flies around in outer space we realize he is boosted by the power of menstrual blood. Uterus Man is a masculine character, but he owes his powers to exclusively feminine attributes.

The work has also become a video game produced by the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum. Uterus Man can use various tricks to fight his enemies, some of which – in line with Lu Yang’s fascination with the biomedical world – have genetic and hereditary properties such as changing the enemy into a weaker and lower-level evolutionary species, causing hereditary diseases or changing the enemy’s sex in order to lower their fighting ability.

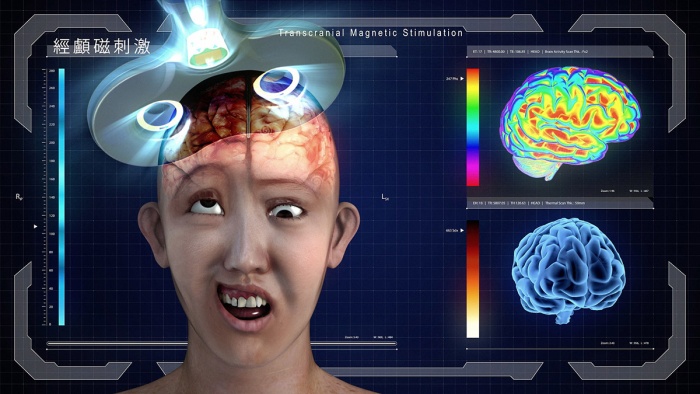

Lu Yang, Kadr z wideo Urojona mandala, 2015, animacja hd, 16 min. 27 sek. Za uprzejmością artystki

Lu Yang, Kadr z wideo Urojona zbrodnia i kara, 2016, animacja hd, 14 min. 37 sek. Za uprzejmością artystki

Lu Yang, Kadr z wideo: Urojona zbrodnia i kara, 2016, animacja hd, 14 min. 37 sek. Za uprzejmością artystki

Lu Yang, Urojona zbrodnia i kara. Widok instalacji w NYU Shanghai Art Gallery, 2016. Za uprzejmością artystki i galerii

Apart from the manga and gaming inspired visuals employed by Lu Yang, there are other elements that draw a parallel with Mariko Mori’s, which is the link between technology and spirituality. Using a wide spectrum of Buddhist iconography, Lu Yang has often paired religion with biotechnology and neurology. In her most recent work, the video animation Delusional crime and punishment, the human creator, God, is a gigantic 3D printer that gives shape to Lu Yang’s avatar, a sexless character that appeared in her previous works Delusional Mandala, 2015.

If in her Tokyo photographs Mariko Mori had used her own body as a performative vehicle to approach themes related to cultural identity and female representations, in Lu Yang’s case the virtually performing body of the artist becomes a machine to be dissected for the purpose of exploring and explaining functionalities of the human body and its components.

With the help of a robotic voiceover and images of Lu Yang’s naked avatar, Delusional crime and punishment illustrates what happens physiologically when our body is subjected to feelings of desire or pain. Though science is here flanked by religious tradition and symbols, both are presented at the same level, with an equal degree of veracity.

As the voiceover announces that “punishments from hell typically correspond to sins committed during life,”11 the MMORPG-like aesthetic suddenly triggers a link between spiritual precepts and gaming, with the artist’s avatar passing through death and a wide array of infernal tortures while hunted by mythological creatures.

In another scene, Lu Yang appears as herself – presumably – or as yet another cyborg girl alter-ego, dancing while dressed in a futuristic armor/costume as she carries on her shoulders what seems to be a weapon that incorporates a gigantic brain. The resemblance of this character’s appearance to Mori’s idol in her Warrior 1994 photograph is striking.

The performing body and the self, cultural-representation and the relationship between human, machine, and digital technology, take yet another visual identity in the work of Korakrit Arunanondchai, born in Thailand in 1986. Having exhibited his work in institutions such as the UCCA in Beijing, the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, and the MOMA PS1 in New York, Arunanondchai – who has studied in the US and currently lives and works in both New York and Bangkok – as Mori and Lu Yang, straddles the line between his own culture and its global representations.

In Arunanondchai’s oeuvre, the concept of oneness and connectivity takes the shape of a porous membrane that contains everything, humans, plants, animals, the living and the dead, the spiritual and the technological. This membrane encloses the world inhabited by the Denim Painter who, more than being Arunanondchai’s alter ego, is the self-projection of his artistic persona.12

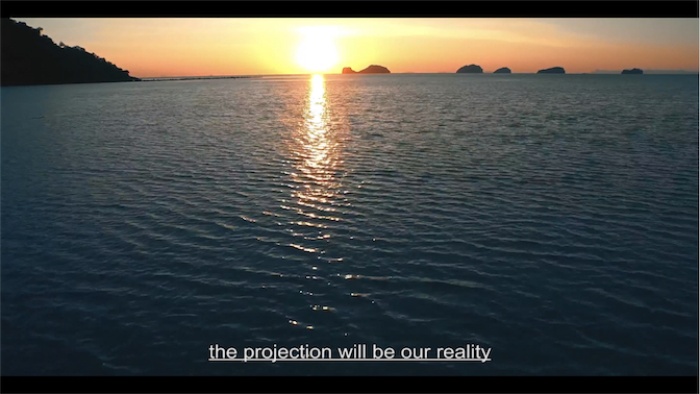

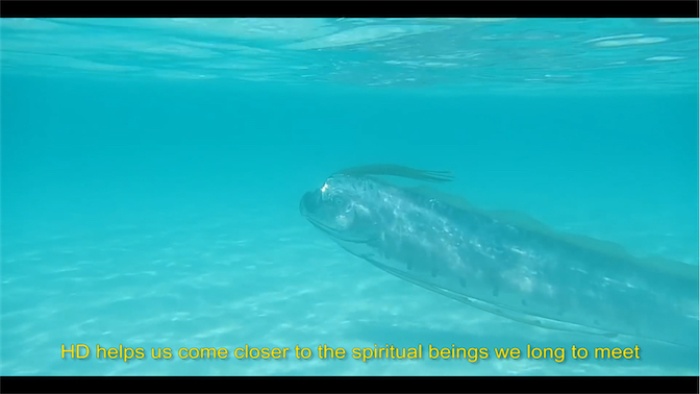

Korakrit Arunanondchai, Kadr z: Painting with history in a room filled with people with funny names 3, 2015, wideo na ścianie LED, 24 min. 54 sek. Za uprzejmością artysty oraz CLEARING Nowy Jork-Bruksela

Korakrit Arunanondchai, Kadr z: Painting with history in a room filled with people with funny names 3, 2015, wideo na ścianie LED, 24 min. 54 sek. Za uprzejmością artysty oraz CLEARING Nowy Jork-Bruksela

Korakrit Arunanondchai, Kadr z: Painting with history in a room filled with people with funny names 3, 2015, wideo na ścianie LED, 24 min. 54 sek. Za uprzejmością artysty oraz CLEARING Nowy Jork-Bruksela

Korakrit Arunanondchai, Kadr z: Painting with history in a room filled with people with funny names 3, 2015, wideo na ścianie LED, 24 min. 54 sek. Za uprzejmością artysty oraz CLEARING Nowy Jork-Bruksela

Korakrit Arunanondchai, Kadr z: Painting with history in a room filled with people with funny names 3, 2015, wideo na ścianie LED, 24 min. 54 sek. Za uprzejmością artysty oraz CLEARING Nowy Jork-Bruksela

Korakrit Arunanondchai, Kadr z: Painting with history in a room filled with people with funny names 3, 2015, wideo na ścianie LED, 24 min. 54 sek. Za uprzejmością artysty oraz CLEARING Nowy Jork-Bruksela

Korakrit Arunanondchai, Kadr z: Painting with history in a room filled with people with funny names 3, 2015, wideo na ścianie LED, 24 min. 54 sek. Za uprzejmością artysty oraz CLEARING Nowy Jork-Bruksela

Korakrit Arunanondchai, Kadr z: Painting with history in a room filled with people with funny names 3, 2015, wideo na ścianie LED, 24 min. 54 sek. Za uprzejmością artysty oraz CLEARING Nowy Jork-Bruksela

Korakrit Arunanondchai, Kadr z: Painting with history in a room filled with people with funny names 3, 2015, wideo na ścianie LED, 24 min. 54 sek. Za uprzejmością artysty oraz CLEARING Nowy Jork-Bruksela

Korakrit Arunanondchai, Kadr z: Painting with history in a room filled with people with funny names 3, 2015, wideo na ścianie LED, 24 min. 54 sek. Za uprzejmością artysty oraz CLEARING Nowy Jork-Bruksela

Korakrit Arunanondchai, Kadr z: Painting with history in a room filled with people with funny names 3, 2015, wideo na ścianie LED, 24 min. 54 sek. Za uprzejmością artysty oraz CLEARING Nowy Jork-Bruksela

Korakrit Arunanondchai, Kadr z: Painting with history in a room filled with people with funny names 3, 2015, wideo na ścianie LED, 24 min. 54 sek. Za uprzejmością artysty oraz CLEARING Nowy Jork-Bruksela

Korakrit Arunanondchai, Kadr z: Painting with history in a room filled with people with funny names 3, 2015, wideo na ścianie LED, 24 min. 54 sek. Za uprzejmością artysty oraz CLEARING Nowy Jork-Bruksela

Arunanodchai’s practice spans from sculpture and painting to multi-media installations, apparel, performance, and videos. Earth, water, fire, air, are recurring elements in his assemblages, where anthropomorphic mannequins and skeletons resurface from piles of mud along with tech waste and pieces of denim clothing. The latter becomes not only the material that gives the Denim Painter his epithet, but it almost embodies a symbol of tribal belonging. Although denim is a clear icon of American subculture and soft-power, it has pervaded Thailand since the ‘70s with the rise of local industrialization, and has hence become somehow a part of the country’s own imagery. Denim is then another symbol with a shifting significance that travels across cultures assuming different meanings. And mimicking its global ubiquity, denim is all over Arunanondchai’s production. For the Denim Painter and his crew it has become almost a uniform, it appears burnt and in pieces in his paintings, and it covers the cushions the spectators lie on when watching his videos.

Most of Arunanodchai’s leitmotifs harmoniously coexist, in Painting with history in a room filled with people with funny names 3, unified by the filmic narrative that evolves around the Denim Painter’s epistolary exchange with Chantri.

Chantri is a spirit that resides in a drone, or a drone with spiritual connotations, whose neutral observing eye is constantly recording from above. The two characters, who speak to each other in voiceover, are at once opposites and equals. The Denim Painter has a human body whereas Chantri is a machine, although to some extent the artist and the drone share the same practice and perhaps mission in the world.

When presenting this work Arunanondchai often accompanies it with a poem by artist James English Leary:

The artist as drone

Is lost in translation and home alone.

The drone is at home high above the world.

It hums the dizziness of freedom.

The artist is drunk on height and flight!13

[…]

Chantri and the artist are observers, recording machines, and in the same way the drone is a spiritual entity, as mythical as creatures such as Naga or Garuda – which is also the national emblem of Thailand. Arunanondchai embraces a techno animism that for some aspects unconsciously or consciously echoes Mori and Lu Yang’s artistic visions. Technology is a vehicle that allows us to reconnect with our folkloric roots where “HD helps us come closer to the spiritual beings we long to meet”14 and drones lift our sight investing our vision with godly powers. For Arunanondchai, who was educated in a Christian school in Bangkok – where most of the people are Buddhist – the spiritual dimension represents, as well, a personal path of rediscovery of his cultural heritage, to the extent that part of his oeuvre is dated according to the Buddhist calendar.

As in Mori’s Oneness, the ultimate catalyzer of connectedness is the physical embrace, as demonstrated by the Denim Painter crew as they perform a hug mob on the rooftop of a Bangkok high-rise building. Painting with history in a room filled with people with funny names 3 alternates aerial drone shots of Thai natural landscapes with urban scenes and music video aesthetics, with the Denim Painter rapping catchy Bangkok CityCity verses while surrounded by his jumping and dancing denim-dressed crew.

As Lu Yang, Arunanondchai brings the afterlife into the mix, envisioning heaven as “a simplified version of the world, recorded in high definition.” He wishes for – or predicts – a future where information instantly becomes knowledge and where “the projection will be our reality.”15

As the Denim Painter looks at Chantri, the artist reaffirms his humanity. While reflecting on the relationship between the real and the virtual, Arunanodnchai unearths issues of identity and alterity. Denim fabric, just as the Manchester United t-shirts worn by the Denim Painter’s crew in parts of the film, are in fact projections that in time have become part of the local reality.

Since the world of the Denim Painter encloses just about everything Arunanondchai holds dear, there is a high degree of personal history intertwined with the more transcending narratives. In the video the construction of the self through a negotiation with its projections is questioned on many levels, from his experience of having a twin brother – who also participated in the artist’s performance a MoMA PS1 in 2014 – to a postcolonialist discourse on orientalization and othering representations.

The funny names mentioned in the title of the work refer to those of western contemporary artists who are still globally part of visual arts studies curricula. Othering these references Arunanondchai shifts the point of view and makes of Western tradition the unfamiliar other.

The identity game requires hence at least two players, the first shapes the other one’s projection and the second reshapes it in response to the production of an empowering self-representation. It is a constant negotiation, a flux of data that contributes to the formation of our own perception at a certain moment in time.

As identity is in relentless motion there is no real self – can it get more virtual than that?

BIO

Francesca Girelli is a curator and writer based between London and Shanghai. For the past five years, she has been working as curator and researcher for Arthub Asia, and she is associate editor of Kaleidoscope Asia Magazine. Since 2013, she also curates DEFAULT (with artist Heba Amin), a biannual research-focused residency organized by Ramdom (Italy). Her research primarily focuses on film and new media, transnational curatorial issues, and transcultural perception of post-colonial and diasporic dynamics.

Among her main projects, in 2012 Francesca co-organized the City Pavilions Project, an integral part of the 9th Shanghai Biennale, and in 2014 she co-curated the 8th edition of Les Rencontres de la Photographie de Fès in Morocco. In 2015, together with Davide Quadrio, Francesca incepted an ongoing series of exhibitions, Crossovers, which has been inaugurated at OCAT Shanghai last year and will travel to Spazio Murat in Italy at the end of 2016. Francesca's curatorial practice addresses artists' active role in reshaping historical narratives by deconstructing and constructing the mechanisms behind the engendering of mythologies and collective memory. Since November 2016, Francesca has joined the Asian Department of the Victoria and Albert Museum to coordinate the development of a ground-breaking digital thesaurus focused on Chinese art iconography.

[1] “Word of the Year 2016 is...,” last accessed 11 December 2016, https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/word-of-the-year/word-of-the-year-2016

[2] Ibid.

[3] President Xi Jinping has reminded the populace, in a message concerning the necessity of governmental control over the net in order to fight the fake narratives engendered online, which he has defined as a medicine inflicted by authoritarian powers, rather than democratic ones. Gianni Riotta, “I fatti non contano più: è l’epoca della “post verità,” La Stampa, 17 November 2016, accessed 11 December 2016, http://www.lastampa.it/2016/11/17/esteri/i-fatti-non-contano-pi-lepoca-della-post-verit-7rqK1viJq99OPL7n5sslMJ/pagina.html

[4] Sofia Lotto Persio, “Read Matteo Renzi's resignation speech in full: ‘I am different. I lost and I say it loudly,’” International Business Times, 5 December 2016, last accessed 13 December 2016, http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/read-matteo-renzis-resignation-speech-full-i-am-different-i-lost-i-say-it-loudly-1594890

[5] Morley, David and Robins, Kevin, “Techno-Orientalism. Japan Panic,” in The Space of Identity: Global Media, Electronic Landscapes and Cultural Boundaries, (London, Routledge), 1995, 147–173.

[6] Edwards, Brent Hayes, “Introduction,” in The Souls of Black Folk, (Oxford University Press), 2007, xxiii.

[7] Lozano-Méndez, Artur, “Techno-orientalism in East-Asian Contexts: Reiteration, Diversification, Adaptation.” in Telmissany, May; Tara Schwartz, Stephanie, eds. Counterpoints: Edward Said’s Legacy, (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing), 183-206.

[8] Iwabuchi, Koichi, “Complicit Exoticism: Japan and its Other,” in O’Regan Tom, ed. Continuum: The Australian Journal of Media & Culture, Special Issue on Critical Multiculturalism. 8 (2), 1994, 1 April 2009.

[9] Allison Holland, “Mori Mariko and the Art of Global Connectedness,” in Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific, Issue 23, November 2009, last accessed 13 December 2016, http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue23/holland.htm

[10] Amy Qin, “Q. and A.: Lu Yang on Art, ‘Uterus Man’ and Living Life on the Web,” The New York Times, 27 November 2015, last accessed 13 December 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/27/world/asia/china-art-lu-yang-venice-biennale.html?_r=0

[11] Excerpt from the script of Lu Yang's Delusional crime and punishment, video animation, 14 min. 37 sec., 2016.

[12] Robin Peckham, “Korakrit Arunanondchai: The Denim Painter’s Universe,” Leap, 9 December 2015, last accessed 13 December 2016, http://www.leapleapleap.com/2015/12/korakrit-arunanondchai-the-denim-painters-universe/

[13] Leary, James, “The artist as drone,” in Letizia Ragaglia, ed. Korakrit Arunanondchai, Kaleidoscope Press, 2016, 55-57.

[14] Excerpt from the script of Korakrit Arunanondchai’s Painting with history in a room filled with people with funny names 3, 2015, video on LED wall, 24 min. 54 sec.

[15] Excerpt from the script of Korakrit Arunanondchai’s Painting with history in a room filled with people with funny names 3, 2015, video on LED wall, 24 min. 54 sec.