Edited by Anna Jäger

Thanks to Bonaventure S.B. Ndikung and Olani Ewunnet for editorial advice and research support.

Disclaimer: this text is a shorter version of a longer text written as curatorial note to an exhibition by the same title that took place at SAVVY Contemporary in 2018 and was curated together with Bonaventure S.B. Ndikung and Olani Ewunnet (as a research curator). Geographies of Imagination is a growing research and exhibition project that manifests itself as a cartographic time-line, performative process of un-mapping the geography of power and a space of discourse. The project is an attempt to rethink, reconfigure and pervert cartographic histories. Each iteration of Geographies of Imagination assumes a different point of departure and thus differing research processes and outcomes.

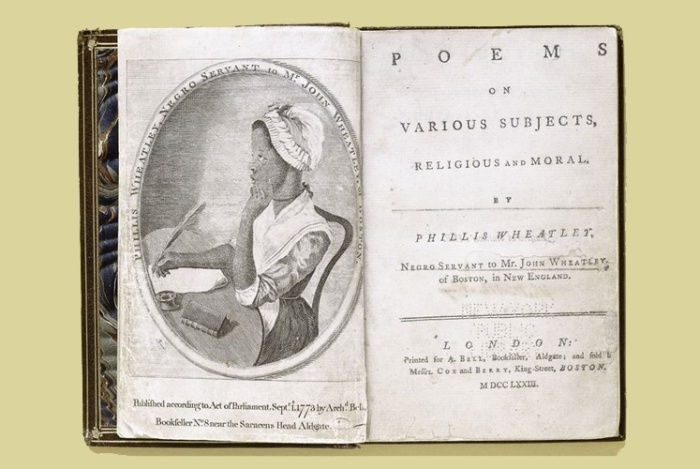

„Imagination! who can sing thy force?

Or who describe the swiftness of thy course?

Soaring through air to find the bright abode,

Th' empyreal palace of the thund'ring God,

We on thy pinions can surpass the wind,

And leave the rolling universe behind:

From star to star the mental optics rove,

Measure the skies, and range the realms above.

There in one view we grasp the mighty whole,

Or with new worlds amaze th' unbounded soul.“

Phillis Wheatley, On Imagination, in Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral by Phillis Wheatley, published 1 September 1773.

Anna Binta Diallo, cyfrowa wersja Tapety z serii: Neither Nor. 2014, Palimpsest. 2016 i Nostalgia. 2011. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

Some notes on the uses of imagination

Around the second half of the 18th century, Phillis Wheatley, the first published African-American female poet and a former slave, wrote a poem titled “On Imagination”. Here, imagination stands as a possible space for the slave´s emancipation, one conceivable through the mind, while the body keeps being trapped in the materiality of existence. Imagination can be understood as a space of resistance, one that allows for the oppressed to construct a being of and in dignity, a space that is less threatening, and a possibility of harbouring an idea of freedom, a space of protection for one’s self and one’s community.

Imagination drove the arduous journeys of generations of migrants across seas and deserts. It is a cognitive space that inspires taking great risks, that can be worth death. A strong courage lies in following the will of imagination, one that is not blind but determined. One that stands behind achieving radical changes, of existential paradigms considered unacceptable. All that is worth risking everything you have.

The Illusion of Power

Imagination, however, can, did and keeps playing a completely different role. The title chosen for this text is a direct reference to academic and anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot´s writings on the issue of false representations, of imaginary geographies essential to the West in the creation of its narrative empires and its reorganization of meaning used to legitimize its supremacy. These attempts run dialectically through much of the epistemological literature of the last two hundred years, and stand as the foundation of academic and museological disciplines such as Anthropology.

Narratives in which the white male is the subject, while other histories and identities are defined around the needs, the life-style and the history of the subject. The other in the white imagination is “‘the savage”’ that slides between heavenly and hellish extremes––, an imaginary other that the West needed to legitimize its supremacy. A supremacy based on “reason and justice" precisely because the other is utopia or barbarism, one that justifies exploitation (of bodies, of land, of labour, of environment, etc.) and dehumanization, offering to a community constructed on a false sense of whiteness the “illusion of power”1.

bell hooks in an essay from 1992 titled Representing Whiteness in the Black Imagination2 starts her argument by asserting that barely any black anthropologists or ethnographers have ever taken the study of whiteness as their focus, at the opposite end for instance to how many white academics, theoreticians or cultural producers have instead engaged with the study of blackness. However, she goes on, knowledge and observations about whiteness have always existed but passed through means mostly pertaining to oral tradition. Because the white other always needed to be well known in order to survive in a white supremacist society, to survive centuries of white domination. In times of slavery, of legal segregation, whiteness was connected to the mysterious, the strange, and above all the terrible. The white other was and, as she writes, still is, an imaginary figure of thought made of the bricks and steel structures of centuries of racism, of exploitation and of enslavement. It is deeply connected to terror. The white other is a terrorist because s/he is terrorizing. It embodies surveillance. It is looking in order to control.

You who are not Ourselves3

In The Origin of Others, Toni Morrison takes the reader through the genealogy of the construction of the other––the psychological, cultural and political work behind the act of othering: of constructing differences that sustain subalternity, slavery and exploitation while divorcing from moral judgement. She describes the need to find an outsider to define oneself and to preserve one´s privileges; of the human impulse, since time immemorial, to define those not in our clan or community as the enemy. This enemy is defined by (a perceived) difference - be it gender, race, class, wealth or else - and an impulse that is ultimately “about power and the necessity to control”4. As Cherríe Moraga argues in her article “La Guera”, many bio-minorities (a recent coinage by Arjun Appadurai, referring to the kind of minorities we speak about here5) have been caged in an oppressive imagery that has ultimately also been internalized by the oppressed. But more importantly, as she goes on “it is not really difference the oppressor fears so much as similarity”6. They fear the loss of their own privilege, they fear the desires of others for what they themselves fallaciously possess, they fear sameness. “What mimetic desire does the figure of the oppressed allow the oppressor to resolve by its victimhood?,” Arjun Appadurai recently asked7? The other, writes Ta-Nehisi Coates in his introduction to Morrison´s The Origin of Others, exists beyond the border of the great “belonging”, something that contributed to producing the sense of anxiety that brought the white and patriarchal supremacist people of the far rights to politically emerge again in recent elections, in the US as much as in several European countries (Italy, Germany, France, Poland, Austria, Hungary, are just a handful of examples).

In “Race in the Modern World - The Problem of the Color Line”, Kwame Anthony Appiah identifies different phases in processes of othering, and particularly in the understanding of race. If issues of racism could already be witnessed from ancient Egypt to Greece - or processes of othering based on what he calls people-hood (differences between people, for instance between Greeks, Egyptians, Sudanese and so on, that already philosophers like Herodotus wrote abundantly about) – then, what we understand as race in the modern world has its beginning in the 19th century with the understanding of race as a biological fact (hence starting with the birth of biology as a discipline). This conception in this particular historical period meets the making of nations and the raising of nationalism, contributing to the construction of the notion of people biologically belonging to precise geographical locations. Hence a body can be attached to geography, a body is constituted by and through the history of the movement and migration of people. A body is politically important because essentially inherited differences come along with specific psychological, moral and intellectual traits. The division of the colonized (and the colonizing) world, the drawing of boundaries and the making of geographies between the colonizing powers determined during the Berlin Conference in 1884 was equally following a logic based on racial bias rooted in a biological understanding of races and their relation to particular places. We can conclude then, as Appiah writes, that: “If nationalism was the view that natural social groups should come together to form states, then the ideal form of nationalism would bring together people of a single race.“8

Planetary Belonging

We can witness many phases and diverse theories, through the course of the 20th century that engage with explaining racial differences, geopolitical dissensions and other forms of alterity. Culture, systems of knowledge and of thought can be considered tools for definition the other, and processes of othering.

We agree with Appiah in thinking that the importance doesn't lie in defining ethnoracial groups but in understanding the social and cultural processes, the governmental and institutional laws and regulations, the neo-liberal agendas that are attached to them. And this is because, to paraphrase what the activist and politician Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez recently synthetized: we can’t really think of “a single issue with roots in race that doesn’t have economic implications” and we cannot “think of a single economic issue that doesn’t have racial implications”9. Othering, and the comfort of othering, is not about difference but power, the subalternity that derives from othering acts is the effect of the exploitation of difference through many forms. Within today´s global conditions under capitalism we could even dare to say with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak that the only two castes this has produced are the rich and the poor10.

With this text, I hope to have highlighted the connections between the varied and conflicting uses of imagination in constructing otherness, the role of geography as a tool of power and the ways power stands at the core of processes of othering. Ultimately, I want to engage with a core question bell hooks poses: how can we – understood as humanity - find a sense of belonging that will encourage and bring us to “embrace all of the conditions of the world” even beyond the human species and towards the earth as a whole? How can we engage in what Angela Davies calls “planetary belongingness”11? How can we stop our impulse to “own, govern and administrate the other”12? How can we undo the comfort in othering? Understanding the multiple reasons behind processes of othering can indeed help us undo them, at least in an effort to change “the present by putting it in a different relation to the past.”13

Maybe we need what Lauren Oya Olamina has in Octavia Butler´s Parable of the Sower14 ––a hyper empathy, a new form of empathy that will let us feel all the pain and all the love of the world, and everything else that exists in between. An empathy that will allow us to love without possession, to belong without identification15.

Karina Puente, Anastazja, z cyklu "(Nie)widzialne miasta". (c) Karina Puente. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

In Italo Calvino´s Invisible Cities, there is one named Fedora––a city connected to desire, but also to love, imagination and possession. Within Fedora there is a museum that contains an innumerable number of crystal globes, all representing the different imaginations and desires the inhabitants projected into the city throughout its history. When talking to the emperor, Marco Polo will conclude:

“On the map of your empire, o Great Khan,

there must be room both for the big, stone Fedora and the

little Fedoras in glass globes. Not because they are

all equally real, but because all are only assumptions.”16

BIO

Antonia Alampi writes, talks, and organises exhibitions and other programs. She is born to Southern Italy but lives in Berlin where she is Artistic co-Director of SAVVY Contemporary, a space wherein epistemological disobedience and delinking (Walter Mignolo) are practiced, and a space for decolonial practices and aesthetics. Recent exhibitions include the group show Geographies of Imagination (curated with Bonaventure Ndikung at SAVVY Contemporary, 2018), solo shows of Ibrahima Mahama (Extra City, 2018), and Jasmina Metwaly (SAVVY, 2018), the group exhibition and public program WE HAVE DELIVERED OURSELVES FROM THE TONAL – Of, with, towards, on Julius Eastman (curated with Bonaventure Ndikung at SAVVY, 2018), the first monographic exhibition of Jérôme Bel (Museo Pecci, Prato, 2017), the performance, discursive and educational program The School of Redistribution (curated with iLiana Fokianaki at State of Concept, Athens, 2017), the group exhibition Extra Citizen (curated with Liana Fokianaki, Extra City, 2017) and El Usman Faroqhi Here and a Yonder: On Finding Poise in Disorientation (curated with Bionaventure Ndikung SAVVY, 2017) among the others. She has written texts and interviews for various publications, including Mousse, Arte e Critica, Flash Art International, Ibraaz among the others and has edited books or journals of artists such as Jérôme Bel, Adelita Husni-Bey, Ibrahim Mahama and Doris Maninger, among the others.

* Cover photo: Anna Binta Diallo, Digital version of the Wallpaper from the series Neither Nor. 2014, Palimpsest. 2016 and Nostalgia. 2011. Courtesy of the artist

[1] Michel-Rolph Trouillot. Anthropology and the Savage Slot: The Poetics and Politics of Otherness (Palgrave Macmillan US, 1991).

[2]bell hooks. „Representing Whiteness in the Black Imagination”, in Cultural Studies, ed. Lawrence Grossberg, Cary Nelson, Paula A. Treichler (London/New York: Routledge, 1992, p. 338-346).

[3] This title is mentioned in bell hooks´s Representing Whiteness in the Black Imagination, when speaking of Michael Taussig´s Shamanism, Colonialism and the Wild Man.

[4] Toni Morrison. The Origin of Others (The Charles Eliot Norton Lectures, Harvard University Press, 2017).

[5] Arjun Appadurai.The Phantom Heimat (Keynote Lecture given at SAVVY Contemporary within the Symposium CARESSING THE PHANTOM LIMB. 'HEIMAT' –PROGRESSION, REGRESSION, STAGNATION?, 1 June 2018).

[6] Cherríe Moraga. La Guera (University of Illinois at Chicago, 1979), p. 32.

[7] Appadurai, Ibidem.

[8] Kwame Anthony Appiah. „Race in the Modern World The Problem of the Color Line“, in Foreign Affairs (94:2, 2015),

[9] Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez quoted in Raina Lipsitz’s portrait „Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Fights the Power“ (The Nation, 22 June, 2018, https://www.thenation.com/article/alexandria-ocasio-cortez-fights-power).

[10] As mentioned in a recent talk, Spivak gave in Berlin: Colonial Repercussions/Koloniales Erbe event series, at Akademie der Künste, 24-26 June, 2018.

[11] As mentioned in a recent talk, Davis gave in Berlin: Colonial Repercussions/Koloniales Erbe event series, at Akademie der Künste, 24-26 June, 2018.

[12] Toni Morrison. The Origin of Others, p. 39.

[13] Jonathan Arac, ed. Postmodernism and Politics, 1986, cited in bell hooks. „Representing Whiteness in the Black Imagination,” 1992, in Displacing Whiteness: Essays in Social and Cultural Criticism, ed. Ruth Frankenberg (Duke University Press, 1997, p. 175)

[14] Octavia Butler. The Parable of Sower (NY: Four Walls Eight Windows, 1993)

[15] Angela Davis, Ibidem.

[16] Italo Calvino. Invisible Cities ( London: Secker & Warburg, 1974, original 1972).