This article was previously published in Currencies of the Contemporary: Biennials and the International in Southeast Asia, "Making Biennials in Contemporary Times – Essays from the World Biennial Forum No 2" (2014).

1983 /1991

The phrase “No More Imagined Communities” invokes a masterwork of the study of nationalism that is also a masterwork of Southeast Asian studies.1 And though prompted to look beyond it, the student of contemporary art in that region is apt to have a hard time doing so, without also looking at or through it. So let me begin by revisiting it – alas, too briefly to do it justice, but attentively, at least, to the long shadow it still casts, and the considerable light it still sheds, on the subject before us: the “contemporary” international survey exhibition. This is, no doubt, a genuflection of sorts, but also an invocation of a spirit, or of several spirits, that find voice in that text and which still have something to say to us.

Imagined Communities long ago became a touchstone of Southeast Asian studies, especially political and historical ones, and so it remains, albeit too often passing unquestioned as received wisdom for studies of art history and for much of the framing of art that has lately come to call itself “curatorial.” It may be inevitable that seminal texts get simplified, but if Anderson’s thesis has often escaped interrogation in cultural studies, its implications have been smuggled less critically still, and often unconsciously, into art writing. To start to correct this, we would need to re-read the book on its own terms, before addressing its intersection with our own terms – with the discourses of modern art. But although I cannot affect such a deconstruction here, for our more immediate purposes it will help to begin by asking: What are the book’s terms? And where might we locate this intersection?

Imagined Communities is above all a book about the discursive production of the nation form, and even in this crude, summary dimension one sees a place for modern art – in most of Southeast Asia an early, if not constitutive, component of that national “assembly.” At the same time, though, this story of production – haunted by Marxism’s reckonings with industrialization, especially Walter Benjamin’s – is also a story of the reproduction of that form, a narrative that both demands and complicates a post-colonial analytic. We will see in a moment that the complexities of reproduction precipitated a telling revision of the book. Imagined Communities is equally a book about media and mediation – a media theory – concerning a program (in Vilem Flusser’s sense of this word), a socio-technical assemblage by which words and ideas come to be circulated and composed so as to produce that national form. That assemblage Anderson calls “print capitalism,” a phrase that summons the very modernity that would come to pass under the sign of Nation, yet encompasses at the same time a good many other modernities: at least, that of the printed word, and the multifaceted modernity of capitalism (of the market economy and capitalist exchange relations; of disenchantment and the emergence of secular powers; of emancipation, class struggle, and representational governance...); but also that of the technologies of reproduction more broadly, of print and later broadcast and electronic media; along with the modernity of language itself, in its more or less timely evolution to reflect and also to produce (or perhaps as often, to retard) the modernity of a society. So many incomplete and mongrel modernities, then – “mottled,” Anderson would say – that came to be peppered across the cities, jungles, river plains, and archipelagoes of Southeast Asia. How have these mottled modernities furnished the modernity of art? And not just its modernity, a modernity that’s still with us, but also its historicity?

Anderson’s thesis is as crystalline, as impregnable now as it was thirty years ago. There’s much in it that remains to be unpacked, not least the importance of the nation form’s origination here in Latin America; and its passage across the Pacific, via the colonial nexus of the Philippines and the circumstantial vector of the Spanish language, a line of flight sketching a newly complete world picture – modern, orbital or “global,” as we now say – one that may be a suggestive precedent for our contemporary art’s “global” self-image. But Anderson was concerned with another encompassment: that which took the imprint of the Nation, not of a world. His “media theory” of print media and national language concerned the media that grounded the historicity and modernity of the imagined community. But this may be a limitation, for while indeed the glue that bound together heterogeneous communities with a common imaginary, these media could never do so comprehensively, nor were their concomitant modernities ever complete. Literacy might become ubiquitous in a given country, say, but would never do so to the exclusion of oral transmission.

In Southeast Asia, far from it. When print did kill off other media (e.g., premodern ones, or contemporary local languages), it moreover created the kinds of displacement, loss, and alienation that retard the cohesive advance of the nation form – hence the modern nation’s elaborate rituals of encompassment.2 Print media’s incomplete coverage of national communities may be contrasted with their sheer penetrability by electronic media, for both social and spiritual intercourse, now the key platforms of many national conversations. (Two conspicuous examples being mobile phones in the Philippines and Facebook in Indonesia.) So if there is a caveat on Anderson’s study, it’s that it tells too well the tale of media in national formation – a complex reduced in academic and bureaucratic parlance to “nation-building” – thus ensuring the containment of that narrative within the frame of that national modernity. This formation was the basis of a certain internationalism, following what Anderson called the Nation’s “serial” logic.3 Yet it did not provide for the reproduction or sharing of much Utopian promise – that of the Bandung Conference, say – but rather, of a modernity more pragmatic and concrete, more opportunistic, as an early multilateralism gave way to the realpolitik of Southeast Asia’s Cold War. With the consolidation of the region’s middle classes and dilation of its public spheres since the 1980s, the ground of national modernity has proved solid, but print media, however powerful, have been unable even fully to encompass most nations, and unable to mediate national conversations about what might follow that modernity.

Anderson himself confirmed the limitation with the addition of a new chapter to the second edition of Imagined Communities in 1991, in the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse. In what he calls a “discrete appendix,” he admits he accounted too brusquely for the transference of colonial to postcolonial forms of administration. “Census, Map [and] Museum,” for instance – the title of the new chapter – were all material and discursive forms of colonial-then-national power, effective, enunciatory, and performative. And they are salutary forms for the media theorist, for they also describe a certain shift from the word to the image: the census paints an ethnographic picture, “a new demographic topography,” he says; the map becomes a popular-national “logo”; while the Museum (all the capitals of Southeast Asia have them) staged the often fraught picturing of a national biography, and even enabled critical re-imaginings of the national community and its past.4 Anderson attributes the late nineteenth century emergence of the colonial museum, on which national museums would be modeled, to the shift from the commercial-colonial regimes of the East India companies towards the properly bureaucratic regimes of what he calls the “true modern colony.”5 He identifies a veritable “antiquities race” amongst the British, French, and Dutch colonizers, with uncolonized Siam limping along some twenty-five years behind. (And one can assume that delegates at a World Biennal Forum are mindful of the importance of this very period in the internationalization of art exhibition.)

Indeed, this Antipodean activity – while certainly not then a vector for modern art – made culture visible in a whole new way, and a more powerful ideological tool; no longer an object of curiosity, its collection, and display no longer simply the window-dressing of colonial plunder. For it also unearthed staggering artistic achievements that flew in the face of all racist-primitivistic narratives, attesting to a cultural depth that called for the creation of “alternative legitimacies” and a new, more elaborate order of domestication, in part through a prolific visual surveying, “a kind of necrological census.”6 These addresses of the past were plotted on maps for the colonial public, often appearing as little logos, half a century before the consolidated “logo-maps” of the nationalists who inherited this archaeo-colonial dispositif. Monuments functioned as images, as signs, ripe for the reproduction and seriality of print capitalism. But I wish to add two observations that Anderson doesn’t make. First, he doesn’t refer to these images as media; what’s important to him is that they render proto-national furniture as reproducible sign, but they supplement, rather than displace, the “images” rendered by the reproducible word of print in national vernacular; and whereas the latter permitted a crucial encompassment, a circumscription that was also an isolation, the exhibitionary media of museum and art – while no less useful at home – would have much greater amplitude beyond the national community. Nor, secondly, does Anderson mention that these monuments were themselves “media” – vast installations made up of thousands of images, pictures not just of a community or state, but of a whole world. In fact, of two worlds: earthly and celestial, whose junction they marked and explained by way of elaborate narratives and designs which enlivened the sacred. “The temple is the body,” writes the art historian, “on which these distinct yet connected ‘worlds’ are inscribed.”7 A structure like the Borobudur in Central Java, for example, was no less worldly in its pretensions and design than any contemporary kunsthalle or biennial. Every square inch of this tourist magnet is stuffed with art. Census, map and museum in one, it not only marked the center of a political and spiritual “sphere of influence” or niandala, but was itself a recursive diagram of that cosmos of which it was the center.

This, then, is the re-reading of Imagined Communities that I would suggest, after Anderson’s revision: Census, Map, and Museum were media – the nation itself was a medium – for the consolidation of an imagined community as cohesive, “discrete and bounded,” but also for its efficient extension and its (exhibitionary) reorganization, according to an iconological seriality, as an image that facilitates the imaging of a world. Could we not likewise expand the parameters of modern art’s history, beyond the straightjacket of national iconography? For however belated their emergence as authors of “modern art,” Southeast Asians were over many centuries plugged into world pictures byway of certain evolving exhibitionary norms, from their own, sacred, premodern worldings, through late feudal and colonial worldviews, to the no less coercive globalism whose bandstand is the biennial. The often shallow internationalism cultivated by the modern postcolonial state is just one step in this larger sequence.

1955

None was more mindful of the political capital that could be cultivated by spectacular, exhibitionary internationalism than Indonesia’s first president, Sukarno, host of the watershed 1955 Bandung Conference that assembled a new, postcolonial world and helped precipitate the nonaligned movement. But however much our better, anti–hegemonic instincts may be aroused by the spirit of Bandung, this “nonalignment” must be taken with a grain of salt. For the conference was a pragmatically inclusive survey of emergent nationalisms, most of them unstable compounds, and some very much “aligned” (those of China, Thailand, and the Philippines for example). That alignment was to prove corrosive indeed.

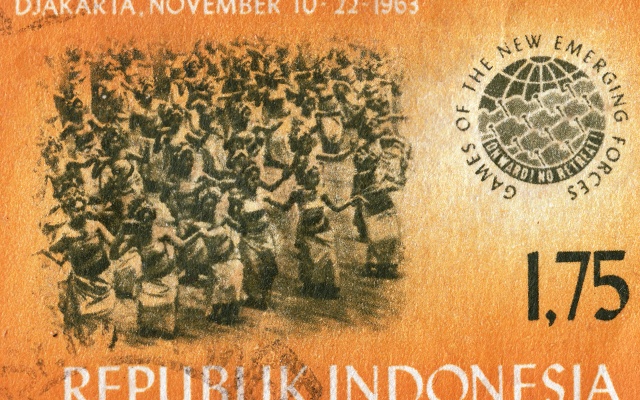

Eight years later, Sukarno’s adventitious Games of the New Emerging Forces (GANEFO) – set up in response to Indonesia’s suspension from the International Olympic Committee for excluding Israel and Taiwan from its Asian Games one year before – were by comparison neither so idealistic, nor so universalist in tenor. The international outlook to which GANEFO gave expression was a fundamentally pragmatic one, like the NASAKOM doctrine, Sukarno’s synthesis of nationalism, religion, and communism, which underpinned his “guided democracy.” There was apparently an exhibition that accompanied the conference in Bandung, as if such a spectacle required further imaging. It spawned a museum too. But to look at this historic convergence of nations and images in a properly art historical light will require a better art historian than me. Instead, I will draw a snapshot of this encounter from two external, literary, and quite personal viewpoints.

The first is a report on the conference by the leftist African-American writer Richard Wright, published in 1956 as The Color Curtain. The second is a glancing recollection in a 2009 lecture by Southeast Asia’s lonely, pioneering art historian T.K. Sabapathy, entitled Road to Nowhere: The Quick Rise and the Long Fall of Art History in Singapore.8 Both men of color; both descendants of colonialism’s massive global redistribution of labor; both postcolonial voyagers in the other direction. Both made lifelong commitments to art, and to the art of sub-alterns, in particular. Yet there was much to distinguish them at the moment their orbits nearly crossed in 1955.

Wright, already in his 40s, after a decade as an expatriate in Paris and with nine books under his belt, was a man wholly given to the struggle for equality and freedom under liberal democracy, and while no stranger to its abuses in the McCarthy era, he had been quite assured of his US nationality –sure enough to have conscientiously renounced it (he became a French citizen in 1947) and yet never shirking its somewhat dubious distinction in the midst of the mostly nonaligned nationals gathered in Bandung. The first edition of The Color Curtain that I read bore the stamp of the University of Malaya, an institution that no longer exists, a national institution of a nation that no longer exists, but whose resources were subsumed into what is now the no less National University of Singapore, where I work. This University of Malaya was the site of the birth – the stillbirth – of a regional art history inaugurated that very year, 1955, with the appointment of the Sinologist Michael Sullivan who started the university collection and offered Singapore’s first ever art history classes. Sabapathy, seventeen at the time, remembers himself as an enthusiastic debutant of the newly arrived discipline. At this point of origin, though, Southeast Asia had no art history to speak of. Sullivan saw its heritage in China and India, a heritage obvious in the faces of the colony then, and now, but less so in its material culture, which accordingly had to be sourced from those far-off places. Neither museum nor syllabus would survive Malaya’s partition and Singapore’s accidental national becoming. Both had fizzled out by 1973.

Sabapathys recollections are vivid but ambivalent. He recalls his first inklings of a newly representational world and new, worldly representations; the first frisson of postcolonialism; and how Bandung crystallized the stakes of decolonization and the emergent Cold War. The university was “not isolated” from these events, but he doesn’t dwell on their effects on art. The infant museum was somewhat insulated, he says, although Sullivan’s lectures led him to see “pictures, sculptures, temples [...] as formations of worldviews.” He “gleaned the faintest of insights into [...] representation; representation of the world as imagined and as pictured,” a perspective then unknown to him, but “glimpsed, faintly.”9 Twice, faintly. A slow awakening, then, to a world of representation, and to representations of a world, dividing.

Now from which side of the divide he would come to see this world was a matter settled in the ensuing years as he set off to professionalize in the US, then the UK.10 But we detect in this tentative awakening to a world picture, to art’s potential to picture a world – and to picture its world, otherwise – the caution and modesty of a young man lacking purchase on that world, a man at home yet somehow out of place. For in contrast with Wright, the internationalist so at home in the world, young Sabapathy was a man without nation. He identified with a place: Singapore. He may have felt “Malayan,” however Malaya was not a nation but a colony of the British crown, then in the throes of anti-colonial struggle, and therefore not represented at Bandung. It would be two more years before its independent Federation and ten more before the colonial entrepot of Singapore had been cast out and had reluctantly become a nation of its own, in 1965, by which time our young art historian was well on his way, studying at Berkeley.

Wright’s account of Bandung begins with a journalistic plebiscite of worldly Asians he met on the way there, followed by discussions with educated Indonesians once he had arrived. Even today we can feel their excitement and their pride, tempered though it was with some indignation, at having forged an internationalism of their own. This pride is an intoxicating thing, and a recent international turn in exhibition making, at and from the art world’s global periphery, suggests that it endures still. Does not the international biennial, in its own decolonizing turns, express just such an excitement? Again, a more thorough art historical treatment will have to wait. But these formal conflations – of the imagined community as assembly, the conference as exhibition, the nation as medium – might at least serve to slow and complicate the assimilations going on under the banner of a putatively “global” and “contemporary art.” If we are to historicize the biennial in Southeast Asia and the worldly aspirations it expresses, we first need to situate it squarely on this backdrop of ideological “alignment,” as a manifestation of the same somewhat liberatory, often indignant, and proud, but above all national consciousness, with all its anxieties, limitations, and pragmatism.

2013

In the time remaining, I will offer a sketch of three of Southeast Asia’s international platforms, by way of a fairly speculative conclusion. My contention is that the history of a global contemporary art is going to require a genealogy of worldliness, since the internationalization it describes in its own domain depends upon much larger and older processes of picturing the world and representing oneself in it, by means of exhibition. An internationalism thus qualified may have to proceed from national contingencies, yet it could also offer ways out of the cul-de-sac of national art history, by not just putting parochial internationalism in its place, but allowing for a skeptical, comparative exhibition history in which the “global” projections of contemporary art too may be grounded in the material and discursive situations that determine them.11 Each international survey show is a kind of mapping – this much is not controversial – but that mapping always frames a national self–portrait. This perhaps underrates the authorial agency of biennial curators and the autonomy (sometimes hard-won) of the organizations that hire them. But just how independent of state imperatives are these agents? Just how immune are curatorial teams to local fantasies of worldliness? The evidence from Southeast Asia makes the limitations on curatorial autonomy all too clear.

Rather than assimilate the art of diverse sites of production in the name of the contemporary, we should historicize the biennial format itself, before acceding to any global typology, in a local genealogy of “worldly exhibitionism” whose horizons are national and whose primary author has in fact been the state itself. Looking then beyond that horizon, it may be that the best guide to a post-national landscape lies in pre-national ones. For premodern Southeast Asia was already, in the words of Oliver Wolters, a geography of “many centers” – centers, not nations.12 We should in any case look past a UN-style pluralism and ASEAN’s fanciful “democracy” of noninterference, to that dynamic, premodern geography, a fluctuating field of obligations rather than universal rights; of uneven development and asymmetries of power; of temporary balance and unavoidable imbalance (i.e., rather more like what we see today around the South China Sea).

Regionalism comes with its own pitfalls, of course. “Southeast Asia” is after all a colonial-imperial construct, and the imposition is as much epistemological as political: not just in the type of administration but in the fact of administration. And it’s not just the kind of geography, but the fact of the geographic itself, as an enactment: a picturing and a writing of place with concrete strategic and legal ramifications. This kind of emplacement is decidedly not native to Southeast Asia.13 Yet postcolonial frameworks have tended to naturalize and reinforce it, drawing lines, fixing boundaries, inscribing people and places for the purposes of administration. However we may wish to discard this frame, a more realistic goal would be to make it reflexive: a regionalism that interrogates and contests its own premises may just be enough to disrupt the unconscious cartographies of contemporary art.

Certainly, that regional window is more revealing than a deep view of any particular Southeast Asian biennial, especially if we mean to historicize the international survey-making where the currencies of our contemporary are generated and laundered. The challenge is to connect this most recent phase, inaugurated by decisive entry into “the global,” with an older, mid-century internationalism whose more salient visual expressions far exceeded the scope of the institution of fine art.

In 2013, three biennials were held concurrently in Southeast Asia: Jakarta’s fifteenth, curated by the collective ruangrupa; Yogyakarta’s twelfth (the second of its “equatorial” stations), curated by Agung Hujatnikajennong with Sarah Rifky; and Singapore’s fourth, curated, allegedly, by a motley crew of some 27 Southeast Asians under the aegis of the Singapore Art Museum. Three competing visions of artistic regionalism, all of more or less local inspiration and design. The cartographic instinct was all too obvious in their isotropic branding devices. But what about the national portraits?

Let us start with Singapore where, perhaps more than anywhere, the biennial’s worldly aspirations are as transparent as its national-instrumentalist calling. Contemporary art there is more an economic than an intellectual vanguard, an instrument of gentrification though almost entirely government funded. After the economic miracle of the 1980s and 90s, a “Renaissance City” master plan was adopted, to cosmopolitanize a place seen as a financial powerhouse but a cultural backwater. Its biennial was thus always already international in scope. The first edition, directed by Fumio Nanjo (assisted by a Singaporean, a Sri Lankan educated in the UK, and an Anglo-Japanese based in Tokyo), accompanied the 2006 World Bank/IMF meeting. Nanjo was also in charge of the second, assisted by a Filipina and a local, artist Matthew Ngui, who went on to direct the third in 2011, assisted by an Australian and a US American. Across all three shows, the selection formula was fairly stable, the geography concentric: with a large local contingent; a spread of regional neighbors shipped in cheap; beyond that, the dim outline of a greater “Asia” and a wider “international.”

Amongst this biennial’s few charms, we could count an unselfconscious sense of discovery, of a region upon whose wealth Singapore has always depended, a region it sits in the middle of, was shaped by, but never dreamed it might actually be part of. One may be tempted to see Singapore’s regional survey-mania – enshrined as it is in state policy – as a kind of neocolonialism, yet what it produces is a succession of fraught, naive self–portraits. This was no less the case for 2013’s pointedly regionalist edition with its sprawling curatorial committee. For Singapore is more Southeast Asian than it gives itself credit for: you can find this bureaucratic regionalism in most of the region’s capitals, especially now, as the ASEAN “community” readies itself for greater economic convergence.14 Yet there maybe another kind of internationalism lurking here, for however neoliberal its national posture, Singapore’s art economy is still essentially socialist. Artists are dependent on the state; the curator, more empowered by the dark arts of administration than by authorship, is even more of a functionary.

The biennial’s seldom-discussed prototype was the locally curated SENI Singapore 2004: Art and the Contemporary, which emphasized the region’s strong collective activity, and established a foothold for nontraditional media in the local exhibitionary landscape.15 Its main exhibition was a “tentative mapping” curated by Ahmad Mashadi and entitled Home Fronts; it reasserted Nation as the primary frame and referent for understanding contemporary art but, to its credit, held that this relation need not be primarily representational.16 There was no attempt to posit universal or essential values on which disparate groups might insist or agree; particularities were stressed over commonalities. But it already expressed – albeit modestly – the regionalism that would emerge as the biennial’s bureaucratic destiny in 2013, revealing the key anxiety that structures the art-worldliness of this migrant society: a fixation on the notion of home. All of Singapore’s regional and international mappings may be read as homing signals.17

By contrast, Indonesia seems more sure of its place in the world, though in 2013, both of its biennials also mapped “locally-thought,” regional internationalisms. Both, in their ways, sketched a contemporary, nonaligned geography; but they arrived there by quite different means. The exhibition in Yogyakarta (Jogja) was the more aspirational, in its commitment to the authored biennial as token of the international contemporary. It occupied public and private institutional real estate. Each edition held under its “equator” rubric sees Indonesian contemporary art paired with that of a given counterpart from an equatorial zone to be mapped out over ten years.18 An accompanying “Equator Symposium” deliberately invokes the internationalism of 1955. The Jakarta show, meanwhile, was held in the car park of the public arts complex, Taman Ismail Marzuki, and various non-art public spaces. Under the thematic banner “Siasat” – an Arabic–derived word for “tactics” – it proceeded by way of a more lateral, artist-to-artist, perhaps more organic and sustained kind of networking that would rather refashion the biennial form, hack it, and localize it for the purposes of a specific community (though this approach must be put down to ruangrupa, not to the biennial organization per se).

The roots of these platforms run parallel. Though they aspire now to international and “contemporary” norms, both began in the authoritarian era as domestic painting surveys with juried prizes – Jakarta in 1974, Jogja in 1983. We would be hard-pressed to characterize much of the traffic in their early years as anything other than modernism, contemporary in only the chronological sense, until the mid-1990s. Neither show was internationalized until the twenty-first century. Both would eventually institute independent, nonprofit foundations, and both receive significant funding from their respective city governments. But those cities are very different indeed.19

Jakarta is the modern national capital, seat of state and military power, and of the market. The associated concentration of wealth has yielded competitors for the biennial, public and private, like the now defunct CP Biennale and the more recent SEA + Triennale. Meanwhile, the smaller, provincial rather than national capital, Jogja, with its claims to Javanese heritage and proximity to important archaeological sites, has long been a center of learning. It boasts the nation’s ranking art school and a large population of students, artists and artisans. Official patronage here has been relatively steady – thanks to the republic’s only surviving pre-independence monarchy – and not as susceptible to the unpredictable moodswings of national politics. Jogja was also home to Indonesia’s first discernibly “contemporary” art space, Cemeti Art House, founded in 1988 and still going strong. Market forces are palpable, but stronger and more enduring are the networks of local artists and autonomous collectives. This biennial has thus been institutionalized and internationalized in a more deliberate and artist-led way.

In broad terms, the last two decades have seen the mantle of both patronage and artistic creation in Indonesia pass from the crony networks of the Suharto era to a younger, more mobile and outward-looking generation that came of age with this new generation pictures for itself. What kind of “international” do you get when you put Indonesia’s two biennial-world together? It is nothing like Singapore’s received, Cold War map, and yet its contours may be just as revealing of a national self-imagining, and just as unconsciously derived.

This other Southeast Asia is archipelagic, and feels no special duty to include the mainland states, nor much affinity with East Asia; despite thirty years of hard and soft sponsorship of Suharto’s “New Order,” the US does not appear on this horizon at all. But it does reach out to encompass much of a once promised, nonaligned ecumene. For the sake of argument, we might juxtapose this worldly map of the two biennials with an older, pragmatic-Nationalist world picture – that of Bandung and GANEFO, for example. It would be hard to overlook the resemblance, a resemblance sure to be strengthened as Jogja’s equatorial platform reaches further afield in coming years.20 A certain internationalism is surely essential to contemporary art’s contemporaneity, but its currency may be more, or less, than meets the eye.

BIO

David Teh is a critic and curator working at the National University of Singapore in the fields of Critical Theory and Visual Culture. His research centres on Contemporary Art in Southeast Asia. He was a co-founder of the Fibreculture network for internet culture in 2001. Before moving to Singapore, David worked as a freelance critic and curator based in Bangkok, Thailand. His projects there included Platform, a showcase of Thai installation art (2006), The More Things Change… The 5th Bangkok Experimental Film Festival (2008) and Unreal Asia (55. Internationale Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen, Germany, 2009). More recently he was the co-organizer of Video Vortex #7 (Yogyakarta, 2011), and the curator of Itineraries (Kuala Lumpur, 2011) and TRANSMISSION (Jim Thompson Art Center, Bangkok, 2014). He is currently preparing an exhibition called Misfits for the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin, due to open in April 2017. David has contributed to numerous periodicals including Art Asia Pacific, LEAP Magazine, Art & Australia, Eyeline and The Bangkok Post. His essays have appeared in Aan Journal, Third Text, Afterall Journal, Theory Culture and Society and ARTMargins. His first book, Thai Art: Currencies of the Contemporary, will be published by MIT Press in early 2017. He is also a director of Future Perfect, a consultancy and project platform based in Singapore.

[1] Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism [1983], (London and New York: Verso), 1991.

[2] Encompassment has long been an impulse for innovation in the region’s official cultures, and the absorption of new media has inspired some of the most imaginative inventions of “tradition.” E.g. the Siamese elite’s propagation of that country’s first printed constitution in the 1930s; Suharto’s inauguration of the developing world’s first satellite (1976) with a ceremonial keris (dagger); or the distributed electronic seance, Ugnayan (music for20 radio stations) (1974), engineered by Jose Maceda for the Marcos regime in the Philippines.

[3] Benedict Anderson, The Spectre of Comparisons: Nationalism, Southeast Asia, and the World, (London and New York: Verso), 1998.

[4] Imagined Communities, p.169.

[5] Emphasis mine. Researchers and artists working with the NUS Museum in Singapore have explored this transition through the lens of the colonial museums of Malaya’s Straits Settlements at that time. See e.g., Erika Tan (ed.), Come Cannibalise Us, Why Don’t You? (exh. cat), Singapore: NUS Museum, 2014.

[6] Imagined Communities, pp.180–182.

[7] T.K. Sabapathy, Road to Nowhere: the Quick Rise and the Long Fall of Art Historyin Singapore, (Singapore: Art Gallery at the National Institute of Education, 2010), p.24.

[8] Published in 2010, op. cit.

[9] Road to Nowhere, p.9.

[10] Sabapathy traveled to California by sea, via Hong Kong, Japan and Hawai’i. So commenced an eighteen-year odyssey of which each step seemed to take him further from his object – a great tradition of Southeast Asian art. After classical studies at Berkeley and London’s School of Oriental and African Studies, he spent a productive but somewhat isolated decade teaching on the Malaysian island of Penang, a period which sealed his commitment to the art of his own time.

[11] This kind of contextualization is a strength of the Exhibition Histories series published by Afterall Books.

[12] Oliver Wolters, History, Culture, and Region in Southeast Asian Perspectives, (Ithaca, NY: Cornell Southeast Asia Program Publications), 1982.

[13] Thongchai Winichakul, Siam Mapped: a History of the Geo-Body of a Nation, (Honolulu:University of Hawai’i Press), 1991.

[14] Conspicuous recent examples include the Southeast Asia-centric SEA + Triennale held at the National Gallery in Jakarta, and Concept Context Contestation: Art and the Collective in Southeast Asia at the Bangkok Art and Culture Center, both opened in late 2013.

[15] The central exhibition, Home Fronts, brought together ten Asian collectives, seven of them from Southeast Asia. SENI’s organizers deliberately sought to counter the “absence of regular, high profile opportunities to showcase” artworks in non-traditional media. Chua Beng Huat, “Introduction” to SENI Singapore 2001: Art and the Contemporary (exh. cat), (Singapore: National Arts Council and National Heritage Board, 2001), p.11.

[16] Ahmad Mashadi,“Home Fronts” in SENI Singapore 2001, p.18.

[17] See also Open House (3rd Singapore Biennale) and Negotiating Home, History and Nation, mounted alongside it in 2011 and curated by lola Lenzi et al. This “homing” is part and parcel of Singapore’s cultural disposition, based on a conviction as prevalent amongst shopkeepers and taxi drivers as it is amongst policymakers: that Singapore itself “has no cultural tradition” and that those of neighbouring countries might therefore be appropriated as national heritage. This is born of the island’s enduring unhomeliness for its ethnic-Chinese majority. Older Singaporeans of any race, though, who grew up before independence, exhibit no such anxiety.

[18] The first equator edition explored India; the second addressed the Middle East.

[19] For a brief history of the Jogja Biennale, see Grace Samboh, “Biennale Jogja Time After Time” archived online at . See also Alia Swastika’s remarks in “Asia Pacific – Part A,” in Ute Meta Bauer and Hou Hanru (eds.), Shifting Grauity: World Biennial Forum No. 1, (Gwangju and Ostfildern: Gwangju Biennale Foundation and Hatje Cantz, 2013), pp.61- 63.

[20] Jogja artist Wok The Rock is curating the next edition (2015) with artists from Indonesia and Nigeria. The following show will focus on a South American country, with the “equatorial” mission set to conclude back in Southeast in 2019.