First published in Feast: Radical Hospitality in Contemporary Art, ed. Stephanie Smith. Chicago: Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, 2013, pp. 360–366. Courtesy of the Author.

Timing matters! The way in which power is divided and affirmed depends on the ability to act on cue when performing one’s part in the social game. The dinner party, banquet, and ball are classic occasions for this game to be played. But since, in the age of "hire and fire," life at work is a permanent talent contest, the pressure to perform and charm is on, perpetually. Recognition is awarded to those who can deliver a good show of potential on cue, when required. The temporal logic governing the economy of recognition is therefore that of the theatrical event – dramatic build-up, crisis, triumph, or defeat. It is what a fast-paced, competitive culture thrives on, as it produces its real-life (soap) operas in everyday social scenarios.

What is obscured by the enhanced theatricality of contemporary "high performance" culture, however, is an altogether different horizon of social temporality: the way time flows offstage when social relations are forged, fostered, and maintained over long periods of time to allow for social services to be provided, cultural events to be planned, and audiences to be built. This is the labor of constant care. It needs to be invested to maintain the social stage on which competitive performers can then make their appearance. The irony is: work that must be done to host an event is highly uneventful. The temporal horizon of sustained social communication, preparation, administration, and maintenance is that of long durations. Many small acts (e-mails, phone calls, etc.) eventually add up to something. But in themselves they are too many, too unspectacular, and too protracted over time to be convertible into the theatrical logic of instantaneous onstage delivery. The award ceremony organizer is hardly ever the prize winner.

This is why a painful contradiction has developed in contemporary society: providing social services and producing cultural events is a growth industry. Still, we lack the concepts to recognize the value of this form of labor as such. The heightened theatricality of "high performance" work culture, on the contrary, is rather geared toward rendering the value of long-term, offstage labor invisible, as it restores power to the age-old role model of the charismatic performer who knows how to play it fast. The contradiction between the invisible labor of hosting and the power of onstage performance, however, has long been present in our culture. In many ways, it seems, we may have technologically upgraded our lifestyles but emotionally never fully outgrown certain traditional value terms and role models.

A wide array of sociopsychological tools of analysis to dissect how power relations are negotiated and imbalances reified in the arena of human affairs are by now at our disposal. And these tools are crucial! Beyond analysis, however, the challenge is to touch on those residual intuitions that determine how we feel we should play our part in the social game. For even if we know that certain things are wrong, that doesn’t mean we wouldn’t still viscerally experience – and intuitively act in accordance with – certain expectations or feelings of entitlement that remain present in the social fabric (and hence make us subject ourselves to particular demands, acquire and develop some skills and sensitivities rather than others, etc.).

Art and literature do arguably have the capacity to tap into, and hence enable us to work through, the emotions that shape our experience on a precognitive level. One stunningly acute articulation of the social intuitions driving the interplay between a dedicated host and a cast of cultural performers takes place in Virginia Woolf’s novel, To the Lighthouse (1927). The relevance of her writing is undiminished – if not increased – because she bears witness to a historical threshold moment in which modern role models for highly individualized cultural performances are not just becoming available but coexisting and clashing with more traditional models of organizing the social. If we admit that we have skirted along this threshold rather than ever fully crossing it, Woolf’s writing indeed gives us an invaluable chance to grasp, on a deeply intuitive level, how the sensitivities of those who host the social relate to the assumptions of those who perform in it. Phenomenologically that means: she permits us to sense how social time is made to flow, who makes it flow, who goes with that flow, and profits from it – and thereby hopefully enables us to exorcise some of the demons and recognize some of the potentials that linger within the horizon of hosting (and) cultural performance.

Virginia Woolf, To The Lighthouse [Do latarni morskiej], Hogarth Press, Londyn 1927. Okładka pierwszego wydania wykonana przez Vanessę Bell. Źródło: Wikipedia.

The Invisible Labor of the Host

In To the Lighthouse, Virginia Woolf lays out a scenario of exemplary hospitality: a family of ten, the Ramsays, spends their annual summer vacation with guests in their country house on the Scottish coast. An aged scientist, a zealous young university lecturer, a faded poet (and opium addict), a couple about to be engaged, and the central female character, a young painter named Lily Briscoe, have what appears to be a wonderful time with the family. The flow of conversation is pleasant and easy on long walks and during dinners. People come together to talk, yet equally happily retreat again to pursue their own activities and read, write, paint, or play in the house or garden. There is a perfectly relaxed, organic rhythm to the manner in which the expanded family convenes and disbands, reassembles, and scatters again. Clocks seem to have stopped ticking. The pace at which days pass into nights indeed seems set only by the pulse of communal life, by the manner in which the heart of the expanded family beats as it contracts and expands again. The temporal experience the novel imparts is thus one of sheer social time, freed from the constraints imposed by the temporal economies of work and commerce. The place that allows time to flow in this manner is the house and garden at the coast, yes, but these in turn are sited in a world opened up by Woolf’s words. In this sense, the space in which social time flows freely is her language, spaced and paced in a manner that is uniquely hers: stunningly steady and succinct, synched to the frequency at which a highly alert mind perceives the colors and contours of the environment: in a crisp, clear flow of impressions. In this sense, the scenario of exemplary hospitality is a situation in the world as well as an occurrence in a particular writer’s language.

Do latarni morskiej, reż. Colin Gregg, 1983, Wielka Brytania. Kadr z filmu. Źródło: YouTube.

Yet, while Woolf tends to her cast of characters with her words like a most attentive host would, the manner in which she portrays the act of hosting in the story is far from ambivalent. For it is very much through the eyes of Lily Briscoe, a young modern woman with artistic ambitions, that she describes the function of the host as wedded to the traditional role of the lady of the house, which the older woman, Mrs. Ramsay, has performed for her entire life. Their relationship is complicated by the fact that Lily Briscoe cannot hope to fully bridge the gap that her modern position creates between her and Mrs. Ramsay. From the latter’s traditional point of view, finding a man to marry is a priority and she deems the desire for artistic accomplishments instead as inappropriate for a woman. As a result, sympathy and support in regard to her pursuits is something the younger of the two knows she cannot receive from the older. Still Lily seeks to be close to the lady of the house in order to Fuldy comprehend the secret of her hosting skills and honor the constant invisible labor through which she renders the inspired conviviality possible. She recognizes that this intuitive knowledge lies in the secrets of a special savoir faire, ‘which if one could spell them out, would teach one everything, but they would never be offered openly, never made public.1 Between the lines, it becomes ever more clear that the very impression that social life finds its own organic rhythm all by itself is deceptive. This is because there is a force behind the process in which things come to seem that way: the lady of the house, mother and host, has perfected the art of invisible social engineering. She is the heart producing the even pulse of conviviality. She senses and preempts possible disturbances, seats people around the dinner table in just the right pairings, and, with her imperceptible touch, erases any blemish and comforts any ego that might have been bruised by the hard words of an unthinking speaker. Remaining invisible – like the divine hand of providence – is the triumph of her art, the proof of her perfection as an accomplished host.

Virginia Woolf, To The Lighthouse [Do latarni morksiej], fragment.

Woolf’s portrayal of the art of hosting is hence equally an act of paying respect and a betrayal. For, by rendering the host visible, Woolf undoes the host’s own understanding of her role by making her an actor walking the stage rather than silently choreographing the social scene from the sidelines. So, despite the fact that Woolf hosts her host in a language that portrays her in the most movingly honorable way, there is next to no intimacy to the relationship between the two women (Lily and Mrs. Ramsay). This is largely because, while the host is in touch with everyone in the expanded family and touches up every mark of discomfort, she remains emotionally untouchable herself. Close to everyone and always on hand when needed, Mrs. Ramsay is infinitely distant and out of reach, alone in her world of ceaseless care. At the end of a long day spent creating the social, Woolf describes how she retreats, literally spent, into the splendid isolation of her selfless mind:

"He went. Immediately, Mrs. Ramsay seemed to fold herself together, one petal closed in another, and the whole fabric fell in exhaustion upon itself, so that she had only strength enough to move her finger, in exquisite abandonment to exhaustion, across the page of Grimm’s fairy story, while there throbbed through her, like the pulse in a spring which has expanded to its full width and now gently ceases to beat, the rapture of successful creation."2

Yet, as she is the force animating the social, her being is immanent to the social fabric and therefore cannot be extracted from that fabric in the form of one distinct persona. Her contours are blurry because she exists in all there is, socially. To talk to her, one would have to talk to the society she creates as a whole. Which one can’t. She is absent from her creation by virtue of being present in each and every one of its aspects. It’s a paradox of theological proportions! Which Woolf chooses to emphasize by means of a sudden plot twist: the host, caring for others, never for herself, hence neither acknowledging nor sharing the knowledge of her decaying health, dies, leaving the world that only she could animate in ruins.

Performing Affect, Consuming the Social, Killing the Angel

Woolf portrays the painful irony of the situation in a manner full of understanding, though it borders on social caricature performed with subtle black humor. The official head of the family, Mr. Ramsay, as husband of the host, is a distinguished thinker and writer. He is not a bad man. Yet still he is so entrapped in his own sense of entitlement that, despite his education and intelligence, he is largely oblivious to the labor of his wife’s considerable efforts to build and sustain his daily reality. Stumbling through the ruins of this reality after her death, he falls back on the only language of feelings that his literary and philosophical education have provided: the idiom of the romantic quest, the words of yearning and lament. He takes his children out on a boat trip in the sea to the lighthouse that they have been looking at from their garden. Out on the waves, in the boat with what is left of his family, the drama of the occasion prompts him to express his desperation at the loss of his wife: a theatrical display of grand emotion, well staged against the sublime backdrop of the solitary tower out at sea:

"Sitting in the boat, he bowed, he crouched himself, acting instantly his part—the part of the desolate man, widowed, bereft; and so called up before him in hosts people sympathizing with him; staged for himself as he sat in the boat, a little drama; which required of him decreptitude and exhaustion and sorrow (he raised his hands and looked at the thinness of them, to confirm his dream) and then there was given him in abundance women’s sympathy, and he imagined how they would soothe him and sympathize with him, and so getting in his dream some reflection of the exquisite pleasure women’s sympathy was to him, he sighed and said gently and mournfully,

But I beneath a rougher sea,

Was whelmed in deeper gulfs than he,

so that the mournful words were heard quite clearly by them all."3

It’s not that his emotions are not somehow also heartfelt. Still they are mobilized with the aim to produce an effect on a public and thus remain inseparable from the theatrical techniques intuitively rehearsed to generate that effect. The inherent theatricality of his emotion evinces the gap that separates his mental world from the universe that Mrs. Ramsay created and sustained. His moment of emotional release is (unconsciously, yet carefully staged as) momentary, instant, eventful, and climatic; dramatically visible. Her emotional labor, on the contrary, has been invisible, lifelong, constant, with no release other than death. His intuitive feeling for dramatic timing, momentary built-up, and climatic effect couldn’t be more different from her sustained sensitivity for the long-durational processes of creating social time. What happens on his stage fails to touch on the emotions she invested by creating this stage. Very sadly so. But while Woolf portrays the head of the family as a self-important, overeducated fool, she equally makes it clear that he merely does what a man in his position, at that time, would have felt and done. He represents what society entitles him to be, a position that his wife, in fact, also considered her vocation to enable and support. He is partially, if not largely, her creation too.

Do latarni morskiej, reż. Colin Gregg, 1983, Wielka Brytania. Kadr z filmu. Źródło: YouTube.

And, after all, he is a writer. Which brings a different irony into play. For Woolf is a writer, too. And her alter ego in the novel, the young woman painter, is as ambitious as he is in his quest for the grand and sublime. So in many ways, ironically, her speaking position is as removed from that of the lady of the house she honors, as is it is close to the man she mocks. His role is utterly defined and limited by the laws of his patriarchal privileges. Still, he lives the life of the mind that the young female protagonist also pursues. So much of what she says about him, mutatis mutandis, could also, in one way or another, at some point in her future career, apply to her. One thing they share, for instance, is a sense of ambition (and its discontents). She is at the beginning of her career and still troubled by doubts about how and whether to embark on it. He is already well established, but similarly tormented by doubts. For even though his works are known, he believes he hasn’t yet received the recognition he deserves. For years now, he has been writing his putative magnum opus, the definitive articulation of his thought system to outmatch his opponents and set the record straight. Even if she doesn’t subscribe to that particular brand of megalomania, the female protagonist nevertheless admits to searching for accomplishments in her art and judges herself severely on these grounds.

Finally, both effectively consume the socialibility that is generated for them by the lady of the house. Arguably, she does so consciously, while he simply takes for granted that the household is maintained and the entertainment of guests arranged for him. Instead of showing his appreciation, the head of the family instead much more frequently uses the social environment created for him as a welcome backdrop against which to stage the singularity of his putative genius (e.g., by pointing out the intellectual shortcomings of his guests to his wife, by secretly lamenting her limited capacity to comprehend the flights of his intellect, and by harboring the feeling that he would have written better books had he not compromised his philosophical pursuits by committing himself to the prosaic reality of married life…). Still, consciously or unthinkingly, as producers of art and thinking, both characters effectively remain consumers of the social life, space, and time that their host creates for them. What makes the difference is the manner in which Woolf manifests her debt, as a writer and artist, to the host, by dedicating To the Lighthouse to the description of her art, and hosting the host in her language. But there is a catch. For while she uses her art to honor the host, Woolf equally keeps pointing to the tensions that, for her, persist between her commitment to artistic pursuits and the moral embrace of the social responsibilities wedded to the traditional role of the female host. In a most pronouncedly aggressive manner, she in fact speaks out against the constraints of the traditional role in her essay "Professions for Women." Here, she asserts that the only way to liberate her practice and write freely was to actively renounce the expectations placed on her as a woman and reject the role of the lady of the house she had previously portrayed in the guise of Mrs. Ramsay:

"In those days—the last of Queen Victoria—every house had its Angel. And when I came to write I encountered her with the very first words. The shadow of her wings fell on my page; I heard the rustling of her skirts in the room. […] I turned upon her and caught her by the throat. I did my best to kill her. My excuse, if I were to be had up in a court of law, would be that I acted in self-defence. Had I not killed her she would have killed me. She would have plucked the heart out of my writing. For, as I found, directly I put pen to paper, you cannot review even a novel without having a mind of your own, without expressing what you think to be the truth about human relations, morality, sex. And all these questions, according to the Angel of the House, cannot be dealt with freely and openly by women; they must charm, they must conciliate, they must—to put it bluntly—tell lies if they are to succeed. Thus, whenever I felt the shadow of her wing or the radiance of her halo upon my page, I took up the inkpot and flung it at her. She died hard. Her fictious nature was of great assistance to her. It is far harder to kill a phantom than a reality. She was always creeping back when I thought I had despatched her. Though I flatter myself that I killed her in the end, the struggle was severe; it took much time that had better have been spent upon learning Greek grammar; in roaming the world in search of adventures. But it was a real experience; it was an experience that was found to befall all women writers at the time. Killing the Angel in the House was part of the occupation of a woman writer."4

So there is a strong ambiguity to the position that Woolf takes vis-à-vis the savoir faire of hosting associated with the traditional role of the lady of the house. On the one hand, she shows the utmost appreciation for the deep understanding of human affairs and power to create social life by hosting the host as the pivotal figure of her novel. On the other hand, she pronouncedly speaks out against the tacit moral imperative to "charm" and "conciliate" that forced the traditional practitioners of the art of hosting to curb their powers in relation to public appearance. How are we today to think through this tension at the heart of her thoughts?

Contemporary Lines of Flight: Angels with Inkpots? Or Anti-Angelic Hosts?

As Woolf herself writes, the spirit of the Angel of the House is a revenant from another era. Still, its invisible spectral presence perpetually grows stronger in the field of social services and cultural production today: the more the demand to turn culture into a spectacle increases, the more the labor of cultural workers organizing those spectacles in hours and hours of communicative work becomes invisible. The labor behind the scenes is effaced by the high visibility of the result it produces. While some aspects of the traditional gender roles have changed and overt patriarchal structures are in the process of being dismantled in many places, certain specters still return frequently to rear their ugly heads. The strong focus on the performative aspects of work in post-Fordist working environments has effectively made working culture more theatrical. The manner in which the value of work is in many fields today determined in the form of so-called "performance evaluations" effectively privileges those who know how to put on a good show in the opportune moment. It massively disadvantages those whose labor cannot be rendered visible in the mode of instant impressive delivery required when the eyes of evaluators are on them.

Virginia Woolf, To The Lighthouse [Do latarni morskiej], fragment.

Since one central aspect of hosting (cultural events, artists, audiences) involves the careful maintenance and cultivation of social relations, its temporal horizon is that of long durations, and its medium is many small communicative acts (phone calls, e-mails, conversations) through which, as Woolf puts it, "the thing is made that endures,"5 i.e., the social tie is tied and the trust is generated on the basis of which collaborations in culture lead to the production of events. None of this can effectively be rendered visible as such, when evidence of professional credentials are expected to be produced on the spot by deans, donors, board members, shareholders, media representatives, etc., during an official or unofficial performance review. To speak about the kind and amount of mundane work – the daily correspondences and financial housekeeping – that actually has to be done to prepare an event is hardly going to sound eventful enough to create the kind of buzz needed to sell yourself as a promising managerial talent or inspired leader. In the cultural field, moreover, the unofficial reviews often enough happen during dinner parties or festive events, so the ability to impressively perform and confirm one’s potentials when drunk further reinforces traditional patterns and privileges. Created and expanded over centuries, patriarchal culture offers a vast repertoire of roles to play, things to say, and gestures that may be performed by a man who needs to jovially assert his claim to leadership in an inebriated state (and ‘ham things up’ without compromising his respectability, e.g., in front of a group of conservative donors or museum patrons). This repertoire seems intuitively accessible to men; its successful use reinforced by the relentless depiction and repetition of such gestures by male characters within popular media; there is little risk of misunderstandings. The repertoire available for women is still limited by the relative short history of their access to public power positions.

A service-oriented labor culture acknowledges social communication as a form of work. Consequently, the work of the mediators and communicators, which, in the days of Woolf and up until fairly recently, would have been understood as a secondary form of productivity has today been acknowledged as a primary force in the production of culture. In the arts, the appreciation of conceptual work that consists of small communicative acts or takes the form of long-term projects testifies to this development, as does the acceptance of the curator as a peer to the artist in terms of creative potentials and cultural credits. In parts of the cultural sphere attuned to these developments, a lot of the poses for dramatically staging the presumptive singularity of male genius that Woolf targeted, have therefore been rendered (partially) unusable. This shift is one important factor for the change in the cultural field brought about by the work of women artists and organizers. Still, the forces of resistance against these changes continue to be strong. Very much so, because the pressure to perform that has arisen parallel to the changes in the working culture in turn strengthens the dominance of conventional patterns and power structures in cultural institutions as well as on the art market and in popular media where grand gestures and fast timing matter more than ever. CEOs, museum directors, and stand-up comedians, for instance, today still tend to be predominantly male. And not a few rely on invisible task forces of angels to run their house from its office while they front the operation and take credit for it in public. This situation is as unacceptable now as it always was.

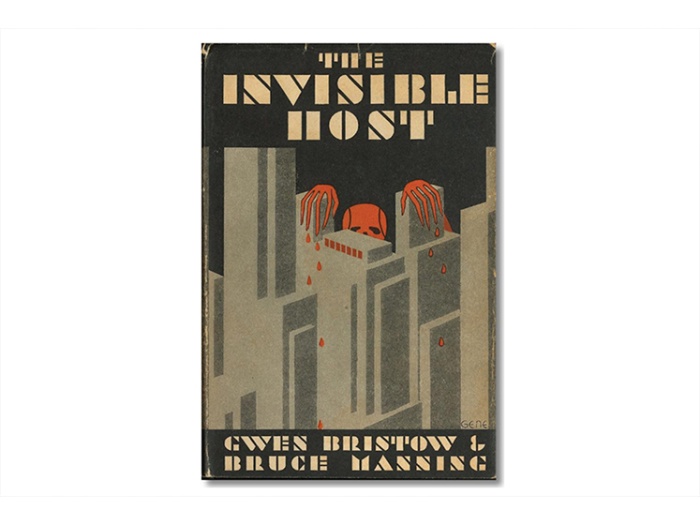

Gwen Bristow, Bruce Manning, The Invisible Host, The Mystery League, Inc., New York 1930. Okładka pierwszego wydania. Źródło: Wikipedia.

This is not the end of the story. To host the hosts of culture in a culture and language attentive to the invisible sides of the art of hosting continues to be a crucial challenge. And here Woolf remains exemplary in her manner of attuning her language to an awareness of the long-term processes in which this labor is realized, without forcing them to prove their worth in theatrical gestures that would only deny their own modalities of constituting cultural values. Still, Woolf hurls the ink pot at the Angel. Is she right to do so? Would it, from a contemporary perspective, not be more just to tell the story of angels armed with ink pots: of hosts who know the secrets of the invisible art of hosting as well as the techniques of commanding the laws of representation? On the one hand, this question is rhetorical. And the answer is, "Of course." On the other hand, however, Woolf’s insistence on breaking the tradition – and her resistance against simply accommodating the knowledge inherent to the traditional role of the lady of the house in her modern understanding of feminist cultural agency – needs to be taken seriously. For what she attacks here is not simply a convention but very much also a morality. She seeks to exorcise the moral sense of duty to be blamed for the intuitive internalization of unjustified social demands. If we attempt to think this symbolic act together with her dedication to hosting the host in her language, then the challenges to be faced are: what concepts and criteria can we mobilize to embrace the labor of hosting as a primary form of cultural production without taking recourse to morality? What would an adequately anti-angelic language be that debunks a conventional repertoire of self-sacrificial altruism and instead acknowledges that hosting could be as amoral a joy and practice as writing?

BIO

Jan Verwoert is a critic and writer on contemporary art and cultural theory. He is a contributing editor of frieze magazine, his writing has appeared in different journals, anthologies and monographs. He teaches at the Piet Zwart Institute Rotterdam and the de Appel curatorial programme. He is the author of Bas Jan Ader: In Search of the Miraculous, MIT Press/Afterall Books (2006), the essay collection Tell Me What You Want What You Really Really Want, Sternberg Press/Piet Zwart Institute (2010), together with Michael Stevenson, Animal Spirits — Fables in the Parlance of Our Time, Christoph Keller Editions, JRP, Zurich (2013), and a second collection of his essays Cookie! published by Sternberg Press/Piet Zwart Institute (2014).

* Cover photo: Virginia Woolf, To The Lighthouse, a cover of the first edition by Vanessa Bell, Hogarth Press, London 1927. Source: Wikipedia.

[1] Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse (San Diego, New York, and London: Harcourt, 1981), 51.

[2] Ibid., 38.

[3] Ibid., 166.

[4] Virginia Woolf, "Professions for Women," in Women and Writing, ed. Michèle Barrett (San Diego, New York, and London: Harcourt, 1942), 57–63, 59f. Originally delivered as a speech to the London National Society for Women’s Service on January 21, 1931. I thank Melinda Braathen for sharing this essay with me.

[5] Woolf, To the Lighthouse, 105.