Chico Togni, zdmuchiwanie liści przy budynku Laboratorium U-jazdowskiego. Warszawa, 2018. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

The Annotated Speech

In June 2018, I was part of Re-Directing: East, a curatorial seminar at the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA), in Warsaw. This month-long residency program, curated by Marianna Dobkowska and Ika Sienkiewicz-Nowacka, focused on the subject of hospitality. It culminated in the public seminar Hospitality as a Strategy of Building Communities, moderated by Konrad Schiller. On this occasion, I presented The Tragedy of the Leaf Blower, a speech that went like this:

Konrad, Ika, Marianna, colleagues, ladies and gentlemen, today, when hospitality is very much the focus of this Re-Directing: East curatorial seminar, I would like to recall the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of 1943. It is described as the largest single revolt by Jews during the Second World War. Worst genocides preceded it, and worst genocides have followed it. Today, 75 years later when there are fewer surviving eyewitnesses to the Second World War, we need to ask ourselves if we have really learned from history or not?

I don’t think so! Yet, in times of migration crises this question is constantly present in public debate, as if time could ever improve human kind. When I was in Poland, a friend touched upon this issue, in an email conversation with my partner, in such a way that I had to paraphrase him in my speech:

“Ghettos worldwide and throughout history, physical and mental, defined by walls and fences, purchase power and ideologies, self-imposed and enforced continue to experience genocide. The rich and optimized, exterminating the poor and outdated, in competition for diminishing resources. Victory to the Warsaw Ghetto!, and enlightenment and freedom from all the world’s genocidal suprematismus. You can create a memorial for all the mass murders in history and a preview of the next one, already unfolding but putting Auschwitz in line with Jericho, as events in the very same tradition of genocidal mass murder, might put you in hell’s kitchen. The Nazis were the most madly and perversely industrious, but not the most efficient, effective, and successful mass murders in history. There are so many ghettos of poor, outcast, and chosen, enforced and elected with visible and invisible borders, like fences, and credit card availability and limits, and soon also fences across entire islands, regions, and maybe even continents, again, like in Roman times and those of ancient China, and gated communities across the world.”1

Ul. Świętokrzyska i al. Jana Pawla II, Warszawa, 2018, Kadija de Paula. Dzięki uprzejmości artystki.

Despite the walls, fences, gates, and ghettos of today, one of my colleagues says that humanity has never experienced such low mortality rates, and that historically we are actually living in a good time.2 Perhaps this is the point of view of those who did not experience actual destruction, and can now eat sushi and tapas over the rubbles of what is no longer here, enjoying the landscape of modern office buildings replacing an old Russian church, and the glass tower of an insurance company standing where the largest synagogue used to be.

The public who listened to it at the seminar, or you reading it now, might feel dizzy with these leaps from serious issues of war and genocide, to the subjective experience of being a part of this Re-directing: East thing. Well, I was dizzy too. Warsaw carries the complexity of being between what is now and what used to be before World War II, and I understand that anyone coming from such a traumatized society might welcome the seeming stability of the present. However, I have a hard time agreeing that lower mortality rates or longer lifespans represent social improvement. I actually see it as a larger, longer-lasting “enslavement” of the workforces of capitalism, which makes me question how we can talk about hospitality in the context of contemporary migration, when we naturalize and consume global capitalism as if we were living in better times?

To be honest, I too come from a ghetto. I’m a polaca da Barreirinha3 da República de Curitiba, a new Christian from a South American dictatorship, whose mediocre education was extraordinarily exemplar in the absolute disparities of the society I grew up in. My Brazilian roots made me a cordial woman, who needs to expand by being social, to extend in the collective for not handling the weight of individuality, and thus seeks to “live in the other.”4 A migrant since my teens I have also been living a nomadic Ostalgic5 life longing for the socialism I never lived, questioning the origins of inequalities and the whys behind injustices.

My ghetto was an immigrant ghetto in an European colony. My grandparents were not killed in concentration camps or war situations. They died of pellagra, tropical parasitic diseases, and banzo.6 In the ghetto where I grew up, Jews pretended to be Christians, and hungry Poles and Italians were a cheap replacement for the recently freed slaves. I come from the great concentration camp called the South, where genocide has been happening for over five hundred years. I personally never experienced war, but I experienced rape, gunpoint robbery, glass, and knifes put against my throat by eight-year-old kids, who have nothing to lose, because they never had anything, because they and their ancestors have been treated like animals to be traded and slaughtered at any time. These are the people who are now knocking on the doors of the North.

The Trap of Hospitality

When I was invited to be part of Re-Directing: East I was excited by the possibility of going as further East as I have ever been to meet people who, due to geopolitical conditions, I have not had the opportunity to collaborate with before. To me, hospitality is to take care of that which is different from you, and thus the challenge of creating an environment where exchanging experience and learning from one another, beyond political clashes, seemed particularly appropriate in a time where we are experiencing a level of polarization not seen in decades.

If the ambiguity of hospitality, lays in the role of guest and host, or the attitudes of welcoming and hostility, then hospitality is centered on the issue of shared resources, and ultimately the question of property and power. As a property-less person, whose practice is based and dependent on shared and ceded spaces, I am clear that my international mobility is part of a contemporary migration movement led by the precarization of labor, and in my particular case, the scraping of the arts. I am also clear that institutions benefit from hosting residents as one of the cheapest possible forms of artistic labor:7 providing housing and food in exchange for creative work. Yet, I would rather be exploited by globalized neoliberalism, than imprisoned by the dictatorship of my home country.

What I mean by the scraping of the arts is the precarization of art as a profession. The art world is divided between a few artists that are part of the market, and a huge number of artists that are part of the non-profit art practice. The ones that are part of the market exchange commodity for money like in any other business. Whether those that are part of the non-profit institutional realm, exchange time for cultural value.8 That is, the later exchanges material, and or intellectual production, for below market values.

Let’s take my participation at Re-Directing: East as an example: I spent approximately ten unpaid hours writing a proposal and preparing an application for this particular open call on hospitality; then I had a long Skype interview and was selected for the program; after that I spent another 30 hours communicating with the institution in preparation for the residency, making travel arrangements, researching bibliographies to share with the group, listing interests to be explored in Warsaw, and making program propositions, as requested by the organizers; in addition to investing 300 USD on visa and health insurance. Once I arrived in Warsaw, the CCA provided me with a stipend of 1000 USD, a live-in studio (equivalent to 800 USD), and travel to and from Warsaw, as well as to Berlin and Podlasie (equivalent to 1280 USD).

In exchange I devoted myself full time, physically and emotionally, to the program. Attended not only the 52 pre-planned hours, but also the extra talks, breaks, and overtime ramblings; answered Facebook group messages, at 6 a.m. or midnight; went to all “non-obligatory,” yet highly recommended and planned trips to the Berlin Biennial, Manifesta, and Podlasie. In the end, what the institution claims to be a 52-hour program distributed over 30 days, to me accounted for approximately 340 hours of activities, spread over nine months: 240 hours during the month-long program, in addition to writing the presentation for the public seminar in the evenings, plus the 30 unpaid hours of preparation and the 70 hours, or more, spread over months of conversation with the institution to negotiate the edits of the text you are reading now. That is, 340 hours of work for 1000 USD and a month of housing.

For the institution the cost of my participation in the program, including the public presentation, and this text, totaled 3080 USD. This is perceived as an expensive investment for such “under-the-skin activities” that need to be fought for and defended; those that do not yield large profits, and have limited visibility with respect to audiences. While this amount is irrisory if compared to what a big shot artist would get for an exhibition, it is still three or four times the salary of the curators of the residency team. A sign of the general precarization of labor, and the scraping of the arts. However low their salaries are, these curators still have a guaranteed monthly income in their home country, which I don’t have anymore, and thus I have paid the cost of instability. A sign of the contemporary migration crisis.

So how can one perceive disadvantage where another perceives privilege? The Dutch theater director Jan Ritsema explains that: “Artists serve Capital as agents and explorers for colonizing the world into economical and ideological globalization… Missionaries of Capital often disguised as its opponents… The artist has a low income, prefers to be mobile and values good quality of life above high or stable income… this is what the neo-liberal semi-capitalistic economies foresee for their future workforce: everybody permanently on holiday but managing the work 24/7 all by themselves… From the slave of somebody else, sold labor, much more people will become slave of themselves.” 9

Departing from this particular context which I find myself in and the welcoming language used by U-jazdowski in describing hospitality not just as a key idea, but the very starting point for this seminar, I proposed to focus my time and collective engagement with Re-Directing: East participants on the way we shared resources and exchanged experiences as a group. I proposed to bring our discourses to the body, by maintaining a common space through a collective generous effort of honest self and institutional critique, through micropolitical acts such as cleaning our common space, self-organizing our collective time and bringing all participants and staff, regardless of function, to the same engagement level.

However, from the very beginning a polarizing atmosphere prevailed. Perhaps there was widespread concern about whether sharing and collaborating was an actual way to develop something honestly and fairly and whether everyone could be included. We all tried to foster collaboration at some point but the common collective response was to go on our individual ways as soon as possible. In the very first days of the program, it became clear that even though we all talked about autonomous movements, precarious labor, gender politics, and popular struggle, no one picked up their dishes from the table. After the revolution, who is going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?10 None of us, because the outsourced cleaner will.

There was no collective response aimed at resolving the great challenge of eating. The response to collective hunger was always resolved individually or by the staff on behalf of the group. This meant that we were never hungry, but we also rarely chose what to eat. The same happened with the program. Comparing it to an ice-cream menu, we were presented with the best flavors that exist, but there was no choice, we had to eat them all!

Eating is probably one of the most challenging daily human efforts, be it to find resources or prepare them. The work of cooking that is commercialized at a wide range of values is often an unpaid “work of love”11 in the domestic context. When eating together fails to happen within the context of collective criticality, class maintenance and power relations become evident.

In this month-long residency this public seminar was probably the first opportunity we had to actually debate the topic of hospitality. Our program schedule was as packed and controlled as any nine-to-five office worker shift, and if you ask me why I didn’t question the program when it was presented to me, I’ll tell you honestly, that I didn’t understand half of what was being said, because of the language, because of the context, because I was rushed to the next activity, without having any idea of what I was getting myself into. Once I understood I had to attend a compulsory program that I was not particularly interested in, going against it became a very personal issue. How could a cordial woman like me, question, criticize, or resist the hospitable and caring people that were embodying the oppressive systemic structure imposed on them by the institutional environment?

“In every situation, there is a right, a left and a center. The left wants to move; the right wants to stay put. The general rule is that the center, the great majority, remains under the heel of the right, through the law of inertia. You know what you are dealing with, anyway: let things stay the same; at least we are familiar with them. Committing yourself to something new is by definition risky.”12

We did not come together to exchange, learn from each other, change ourselves or the world, but rather to gain and maintain access to the “privilege” of future work, even if precarious, low wage, without benefits, security, or dignity. In times of increased competition for diminishing resources we will hold on to anything. No one is willing to lose, to risk, to change, or to challenge, we rather listen silently to what we do not understand or even disagree with, and wait for it to be over, but we wouldn’t dare to interrupt, to be rude, to say no, or to voice the truth. That would be too much, it wouldn’t be appropriate, it could hurt future opportunities. And the future value of money is all that matters and this is why in the times we live in, artistic endeavors do not bring about any real change.

I acknowledge my privileges, particularly the mobility and access that allows me to partake in this and other self-enriching experiences of which, even though I am grateful for, I would rather be critical of than perpetuate a class maintenance system disguised as engaged, conscious, or hospitable.

Artistic practices keep adjusting its methods in response to institutional offers that are shaped by capital demands. Today in times of intensifying migration we talk about hospitality, yesterday it was gender politics, the day before it was climate change, but the institution won’t stop printing catalogues that will end up in the garbage, we won’t stop eating quinoa from Peru, avocado from Chile or shrimp from Bangladeshi migrant trade boats, because no one dares to stop the machine.

So, what would be a possible solution? How to slow down the machine while we are on it? How can we engage at a creative and intellectual level without being exploitive or hypocritical? A good start is to think more and do less. The value of residencies lays in the time and space they provide for creation. Thus, giving space and time for writers and thinkers alike would be just as hospitable as it is the case for artist residencies. If the idea is to foster collaboration, which seemed to be the case of Re-Directing: East, then space and time means a less-planned program and more time to share expertise, make connections, and create together. To apply hospitality and care as resistance against oppressive structures and systems, it is necessary to pause the institutional speed to look at the oppressive structures before reproducing them with our bodies by making a conscious effort to be truly open and available, rather than controlling and demanding. And please, no trendy topics, let’s stop with the instrumentalization of the arts, it’s enough, we cannot save the world! These palliative symbolic discourses collaborate with the deradicalization of movements. It appropriates radical demands into a mainstream discourse empty of practice which gives the illusion that our engaged discourses abolish us from our unengaged questionable actions.

Zepsuta Europa: postaraj się o prawdziwą robotę, Chico Togni, 2018. Dzięki uprzejmości artysty.

The Tragedy of The Leaf Blower

The leaf blower is a great example of the never-stopping machine. He wakes me up every sunny day at 7:30 a.m. blowing leaves beside the Laboratory Building (one of the two buildings of the CCA, where I was living). For the institution, the landscape contractor and the gardener, the leaf blower is a gift from God, saving hours of tedious raking and grooming, but the crude little two-stroke engines blower is a pollution bomb: running it for 30 minutes creates more emissions than driving a pickup truck for 6000 km. Those emissions constitute a public health hazard for anyone in the vicinity, but especially for the poor bastard running the thing at 100 decibels, but who cares about the lungs and ears of the leaf blower? The tragedy of the leaf blower is that it makes assholes of us all, users and neighbors alike.

We can talk about hospitality as a revival of collective thinking and the community stronghold, but if in real life we don’t ask ourselves how we are feeling throughout the conversation, there is no point in talking about hospitality, community, or collectivity. We can talk about hospitality as a total system: universalism vs. humanity, but if we can stand a three-hour theater play on modern slavery in Warsaw and cannot engage at a human level with an Ukrainian bum who asks us for a cigarette during the intermission of the play, there is no hospitality or humanity that can be talked about. We can talk about hospitality as a tool for emancipation; but if we don’t let our administrative staff or intern present themselves as part of a team we call non-hierarchical, there is nothing for us to talk about. We can talk about hospitality and self-recognition, but if in real life you don’t help me hold the door when I’m carrying a lot of luggage trying to enter the building we live in together, there is nothing for us to talk about.

To me, the real moral sense which guides our social behavior is instinctive, based on the sympathy and unity inherent in group life.13 Mutual aid is the condition of successful social living and if we think that things are not being run fairly and mechanisms are not reciprocal, then we should seek for collaborative solutions, and not individualistic responses, which ultimately only serve to further isolation and protectionism. I have tried to make clear to you what I believe hospitality is and I think this always begins at home, at the body. The more we succeed in overcoming division within and amongst ourselves, the more freedom we will have to focus on solidarity, cooperation, and hospitality. Fundamentally, the solutions are always simple: we can leave no one behind, we must open doors for each other, share the weight with one another, and NO we cannot leave the cleaning for later, because someone will end up doing it for us.

I would like to thank my hosts for the efforts made in being hospitable. I may not be the best guest, but I am certainly an even worst hostage. I know it could have been worse, but it could have been better too. So please let’s try to learn from history and remember that freedom is a possibility only if you are able to say no. To step out of ideology hurts, it’s a painful experience, you must force yourself to do it, it is the extreme violence of liberation. If you simply trust your spontaneous sense of well-being you’ll never be free. Freedom hurts.14 Freedom kills.

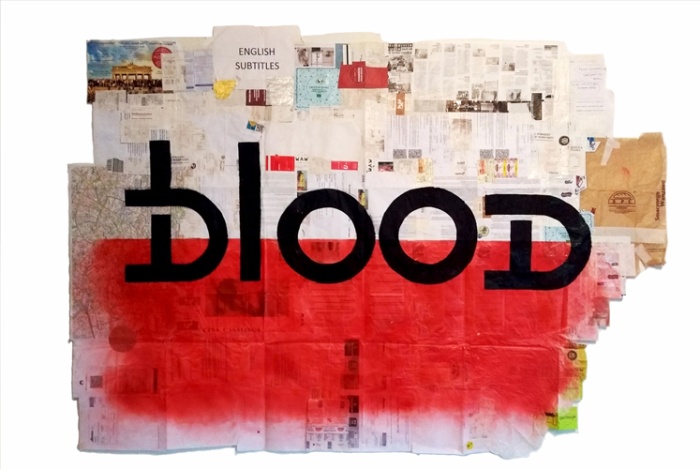

Krew, Kadija de Paula & Chico Togni, 2018. Akryl na znalezionych papierach, naklejkach i opakowaniach po produktach skonsumowanych przez miesiąc w Warszawie. 140 cm x 200 cm. Dzięki uprzejmości artystów.

A special thanks to Chico Togni, for the research assistance, love and support that made this text possible.

BIO

Kadija de Paula combines food, text and performance to create situations and happenings that question the value of labor, resources, and social habits. From a background in cultural management, she often works in collaboration with other artists to make institutional critique through self-organized alternative economical experiments that challenge the limits of life and art. With an IMBA in Arts Administration from the Schulich School of Business at York University, and a BFA in Photography from OCAD University, both in Toronto. Kadija was facilitator and mediator of residencias_en_red [iberoamérica], a platform of artist residencies in Latin America and Spain; and acted as Visual Arts consultant for UNESCO while simultaneously producing one ton of dough at pizzeria Ferro & Farinha in Rio de Janeiro. She is author and editor of independent published works, and co-translator of José Oiticica’s Anarchist Doctrine Accessible to All by WORD+MOIST PRESS Livorno. Kadija has presented her research, performance and visual work in seminars, exhibitions, and happenings at Sesc São Paulo; Q21 MuseumsQuartier Vienna; Wachauarena Melk; 32ª São Paulo Art Biennial; MATADERO Madrid; Villa Romana Florence; Jan van Eyck Academie Maastricht; Casa Daros Rio de Janeiro; United Nations University Tokyo; ArteBA; and MAM Medellin, amongst others. In 2018, she is a laureate of L’institut Français for a residency, in partnership with Chico Togni, at Cité Internationale des Arts Paris.

https://kadijadepaula.hotglue.me/

Video documentation of Hospitality as a Strategy of Building Communities Seminar (July 1, 2018, Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art) is available online:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zsbEfgj43vE&t=483s

[1] Paraphrased from Michael Altherr’s email to Chico Togni in June 2018.

[2] Comment made by the Polish curator Mirela Baciak at Re-Directing East 2018.

[3] Expression referring to the Polish immigrants who established themselves in the neighborhood of Barreirinha in Curitiba, the capital of Paraná, Brazil, at the end of the 19th Century.

[4] Sérgio Buarque de HOLANDA. 1936. “O Homem Cordial.” in “Raízes do Brasil” (26th edition) 1995, p.147. Companhia das Letras, São Paulo.

[5] The nostalgia for the socialist past in some post-communist countries as defined by Slavoj Žižek. 2016 in “No Way Out? Communism in the New Century” in The Idea of Communism 3: The Seoul Conference, edited by Alex Taek-Gwang Lee and Slavoj Žižek. Verso Books, London.

[6] Banzo (from the Quimbundo Mbanza, “village”) refers to the feeling of melancholy in relation to the native land and the aversion to the deprivation of freedom practiced against the black population in Brazil at the time of slavery.

[7] Compared to exhibitions, commissions, and sales.

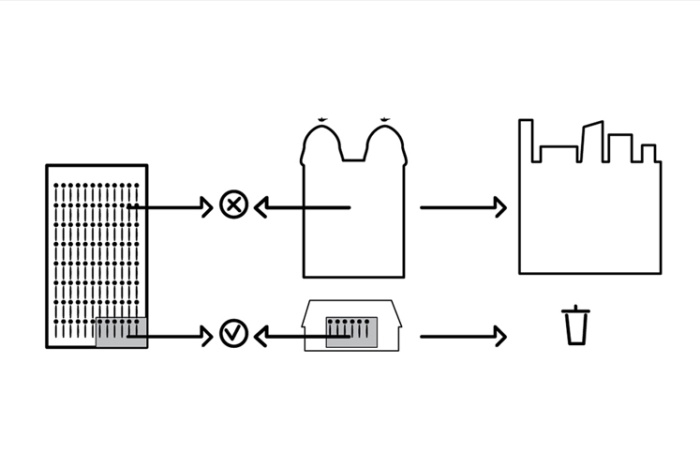

[8] Lize Mogel. 2009. “Two Diagrams: The Business of Art and The Non-Profit Art Practice” In Art Work: A National Conversation About Art, Labor, and Economics. 2011, US.

[9] Jan Ritsema. 2016. “Property Revisited or Let’s Help History Take Another Direction”. In “Identities: Journal for Politics Gender and Culture” (2015–2016). Issues No. 23–24, Institute of Social Sciences and Humanities, Skopje.

[10] Mierle Laderman Ukeles. 1969. “Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969, Proposal for an exhibition ‘Care.’”

[11] Silvia Federici. 1975. “Wages Against Housework” Falling Wall Press Ltd. Bristol.

[12] Cécile Winter. 2016. “Liberating Dictatorship: Communist Politics and the Cultural Revolution” in The Idea of Communism 3: The Seoul Conference, Ed. Alex Taek-Gwang Lee and Slavoj Žižek. Verso Books, London.

[13] Pyotr Kropotkin. 1897. “Anarchist Morality” pamphlet published in Moscow.

[14] Slavoj Žižek. 2012. The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology. Directed by Sophie Fiennes and distributed by Zeitgeist Films, USA.