The hippocampus is the part of the brain that retains special representation of our surroundings and participates in directing spatial navigation. Its cells combine into a map of the environment and are known as place cells.

A Look at the Tatra Mountains in Slovakia

I feel as if I have barely walked a few paces in Slovakia – not enough to cover a distance sufficient to empathize with the local population. I travelled more extensively in Thailand, during my stay in Bangkok in 2013. That was my first journey to the Far East. Before I saw the Tatra mountains – for the first time from the Slovak side – in the window of the Messy Project Space art gallery there, I had confronted their native representations. There are basic differences in the traditional methods of representing space-time in the West and the Orient. In Eastern representations, space is shown in axonometric views and timeless cycles. The Western takes employ perspective and involve a linear representation of space-time, in which situations have a beginning and an end. This is, of course, a generalization.

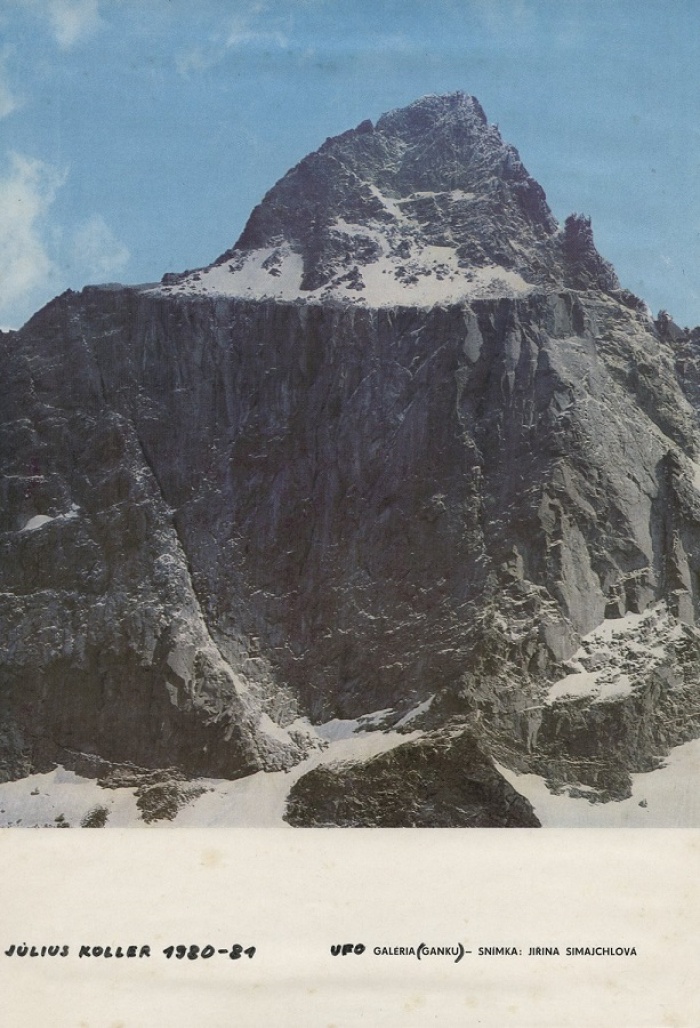

U.F.O - Galeria Ganku, Július Koller. Zdjęcie: Niwat Manatpiyalert. Dzięki uprzejmości Messy Project Space (Messy Sky).

In the Western tradition, axonometric projection has been used mainly in technical drawing. It is an attempt to view things objectively. An axonometric drawing makes it possible to measure an object or to determine its precise distance from another object. The Eastern tradition rarely employs linear perspective, although it is not unknown.

Chitti Kasemkitvatana, the co-founder of Messy Project Space (together with artists Pratchaya Phinthong oraz Thakol Khaosa-ad) , showed us the way to a nearby Buddhist temple, with paintings by Khrua In Khong, one of the most acclaimed Thai artists and mentor of the modernizing King Rama IV. Traditional Eastern representations have been replaced by views based on perspective, which reference the Western canon of landscape painting. The Thai people are proud of the fact that their country has never been colonized. The modernization of social mores was intended to counteract the imperialist inclinations of Western powers, while the adoption of Western fashion, language and diplomacy – was to both help the Thai population understand the advancing external forces and facilitate a Western understanding of the complexities of Thai culture. Khrua In Khong had never visited the Slovakian Tatras. In fact, he had never been to Europe at all. He learnt from those arriving from the West and used the power of his imagination.

The temple was some half an hour’s walk from the gallery, to the north. The paintings looked slightly inept. The perspective introduced had numerous vanishing points. However deliberate this may have been, the end result was reminiscent of axonometric representations using perspective. This multiplicity of vanishing points is typical of the collage. An agglomeration of images gives the impression of providing a choice of the viewing point. It also offers an authentic collective vision.

Malowidło naścienne w świątyni Wat Borom Niwat, Khura In Khong. Źródło: Wikimedia Commons.

The form of representation plays an important part in the process of memory, for one. Can we destroy a concept merely by the mode of its representation? Can a universal phenomenon be put to an end by giving it a point of confluence? I have a feeling that iconographic shifts are the most powerful in mediating the flow of matter and phenomena. The change of perspective has a significant impact on the interpretation.

Wyburzanie osiedla Pruitt-Igoe. Autor nieznany. Źródło: Wikimedia Commons, (c) U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research.

Osiedle Pruitt-Igoe. Autor nieznany. Źródło: Wikimedia Commons, (c) United States Geological Survey.

A Roman Room in Palmyra

For Polish architects, the journey to the Middle East and North Africa has often been a journey to the birthplace of their discipline, the Roman cities of Palmyra and Leptis Magna or the Great Mosque in Samarra. It could also prove to be an opportunity to discover the vernacular architecture of Damascus, Aleppo, Baghdad, and Algiers or the colonial modernism of Algeria and Libya.

Working on location involved the need to find a common language, often redefining the architectural practice of producing images rather than space. In private and government collections, the image became the means of evoking and controlling the local memory. This applied particularly to the notions of an Arabic city, a desirable image both from the point of view of the regimes that played down the ethnic and religious diversity of the population, and by the tourists whose Oriental fantasies were being reinforced. The focus of attention on images underlined the working conditions of the Polish architects in Algeria, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Syria, and the United Arab Emirates. Impressive drawings were often the sole means of persuasion at the disposal of the architect.1

Kościół Najświętszej Maryi Panny Królowej Pokoju na osiedlu Popowice we Wrocławiu. Zdjęcie: (c) Maciel Lulko, Architektura VII Dnia. Dzięki uprzejmości autora.

Its picture had been a part of my room for years. From the West, it was accompanied by the desert. We imagined that beyond it, there spread the sea. Today I know that it was the Gulf of Persia.

“You have built us quite a pretty mosque,” Wojciech Jarząbek was supposedly told by Cardinal Gulbinowicz on the completion of the new church in the Wrocław district of Popowice – a building in whose form one can see references to both the city’s gothic tradition and the architecture of Islam. Jarząbek was one of the architects who had travelled to the Middle East. Before working on his projects in Poland, he had worked in Kuwait and the UAE.

Memory is the body’s special ability to receive information from diverse sources as well as segregate and record it in the form of memory traces. Spatial memory is a specific kind of long-term memory, within which two varieties can be distinguished: idiothetic – based on self-motion cues, and allothetic – relying on external visual images.

The Roman Room is a mnemonic technique that aids the remembering, storage, and retrieval of information. It relies on associations of images with places in a known environment, whether real or imaginary.

The process, materiality

For their project Dust, the curators Anna Ptak and Amanda Abi Khalil invited artists from Poland and the countries of the Middle East. The exhibition at the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art (2015) was inspired by Reza Negarestani, who, in his Cyclonopedia, observes, “Each particle of dust carries with it a unique vision of matter, movement, collectivity, interaction, affect, differentiation, composition and infinite darkness.”

Widok wystawy "Kurz". Zdjęcie: Krzysztof Skoczylas.

The standard creative process of the architecture of an exhibition tends to follow a similar course. Its first task is trying to understand the curatorial text and translating it into a spatial concept. Next comes the analysis of the theme. A sketch on the back of an envelope indicates the rough idea. This sets the production in motion. The full conceptual blueprint arrives, based on a virtual or actual model. In the construction process, all the technical details are sewn up as is the overall cost of the works. finally, the project comes into being, overseen by the designer. In the case of the exhibition Dust, the process was reversed.

There was no design. The prototypes arrived straight away in the exhibition space. The Castle had been chock-a-block with non-inventoried objects – furniture that had seen better days, plinths, second-hand floor coverings, elements of old wall structures – remnants of previous exhibitions or art installations. They were all stored in cellars, rarely visited. It seemed natural to include all these things in the exhibition.

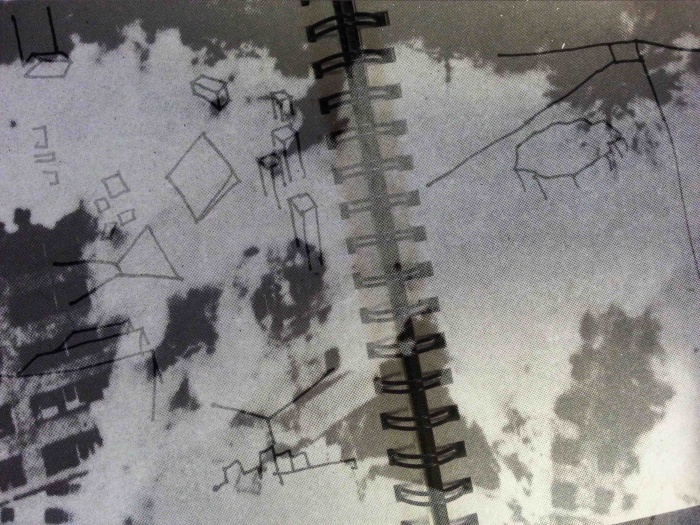

Boom, dust, smog, fallout

In my remote communication with the curators (as Amanda Abi Khalil was not in Poland and Anna Ptak often worked on the program from other locations), I employed a virtual model, which reproduced the progress in the prototyping of the gallery. The conduit was both the model itself and the selected frames. Most of the manual sketches were produced in the final stages of the realization, when the final touches were being put to the dynamics of the exhibition as a whole. These sketches were the key for me. They clarified the conceptual order of the exhibition. I used them interchangeably with the physical representations of the architectural elements in the gallery. I did the sketches in axonometric, broken perspectives, in various spatial shortcuts, with elements independent of one another, seen together or in spatial chronology.

Zdjęcie: Krzysztof Skoczylas.

I built the architecture myself, on some occasions with any necessary help coming from the assembly team, who had been used to shift the entire content of the storerooms to the exhibition hall. The workers were less than enthusiastic at the prospect of tampering with the forgotten mass, particularly as after the end of the exhibition it would have to be taken back to storage.

It is very likely that a routine approach, with a clearly outlined scheme and a definite timetable would have been less disquieting to the team. The character of the project demanded, however, that decisions about the exhibition architecture had to be made ad hoc. All gestures began to transcend the run-of-the-mill procedures, acquiring significance. Tampering with the abovementioned matter triggered an examination of the institution’s reactions and its resistance to non-standard solutions, but it also drew attention to the problems of ecology and managing resources of the institution. I left the subsequent fate of the re-formed matter up to the institution, suggesting only the possibility of cataloging the previously invisible resources. The architecture of Dust probably became the actor of both gesture and inactivity. The institution had to, and did, make a decision on how to manage the discovered resources.

This process was revealed publicly to a modest extent. A mention in the guide or any rumor probably barely attracted attention. Verbally explicit information did not require emphasis. The architecture of Dust not only touched on the management of resources but also on the understanding of their materiality. The experience of the space created – dedicated to the general public – remained accessible to the senses, thus exceeding the physical limits of the object.

Presence – image, space, body

The exposure of artists’ works is another level altogether of the exhibition construct. Usually, curators have their relational network clear. We aim to recreate it spatially.

In the rooms there had already functioned a spatial structure with spaces allocated to specific works. This was not a closed structure; it made possible the shifting of works from their initially allocated spots, and indeed this was taking place, provoked by a questioning of how we understood the space of artistic work and the limits of its autonomy. Each artist has his or her expectations and if they have been made explicitly, they are respected. What was particularly important for me, however, was the question of what kind of situation we place the audience in, the question of its presence and participation.

In the exhibition space there were intimate places, permitting relation with individual art works. Yet the space also offered broad-sweep points of vision, that allowed one to view the exhibition as a whole as well as providing the public with a chance to become a part of that whole.

In the center of the exhibition we placed the Settling Space, or the self-forming auditorium, built as part of the same system and in the same idiom as the rest of the architecture – more radical in its format, however. In principle, it enabled the curators and the architect to totally divest themselves of their power and control over the space, while simultaneously retaining their part in shaping it. Thanks to the mobility of the elements as well as the visualization of traces of the public and of artistic actions, the place became a map of the exhibition concept.

Widok wystawy "Kurz". Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka, 2015. (c) Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej Zamek Ujazdowski.

Widok wystawy "Kurz". Zdjęcie: Bartosz Górka, 2015. (c) Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej Zamek Ujazdowski.

If the curators and artists have no other specific requirements, I try to understand the exhibition space as a tool for aiding the individual view. Artists’ works are presented so as to enable the public to choose their preferred perspective (albeit not always in the most comfortable situation), thus gaining or maintaining subjectivity vis-à-vis objects and events. This will at all times be a subjective situation but it is my intention to keep fluid the boundary between the space for the public and the space for the artwork. In exhibitions such as Dust works remain in a relationship. Together with the architecture and the public, they create the environment in which architecture is a function of memory, supporting the individual record and a subsequent re-creation of the experience – both of body movement and the image received.

Widok wystawy "Kurz". Zdjęcie: Krzysztof Skoczylas, 2015.

Looking at the Slovakian Tatras through the eyes of Július Koller

In relation to the universal character of objective reality, subjective actions and cultural operation create situations directed at the future – they will result in a cosmohumanist culture, where – instead of a new artistic aesthetic – there will be a new life, a new subject, consciousness, creativity and a new cultural reality.2

I have always found small utopias seductive. U.F.O. - GALERIA GANKU is a photograph appropriated by Július Koller of a peak in the Tatra mountains from the Slovak side. I saw this photographic collage in the gallery’s window, with a clear view in the background of the roof tops of Bangkok’s Old City.

Galeria Ganku, Július Koller . Źródło: "Július Koller, Galéria Ganku", red. Daniel Grúň. Dzięki uprzejmości Daniela Grúňa.

In his praxis, Koller postulated endowing real subjects with subjectivity through viewing them subjectively. He thought that the only way to gain subjectivity in a technocratic environment was via individualization.

For his utopia, he chose Ganek, an almost three-thousand-meter-high peak in the Tatras, situated close to the border between Slovakia and Poland. A particular feature of the mountain that stimulates the imagination is that below the peak it has what looks like a well-defined terrace, known as the Ganek Gallery. In spite of being located close to the main Tatra ridge, the Gallery is inaccessible to tourists and can only be reached by experienced climbers. It was in that Gallery that Koller placed his utopian exhibition space.

The artist has cut out photographs of the mountain range from Tatra magazines, creating collages, to which he adds information about forthcoming exhibitions. He has organized a board of directors from amongst his friends, sending them invitations to fictitious exhibitions. This “mental space,” as he refers to it, is very safe. It requires no real action, artistic intervention, clashes with critics, reproduction of artefacts or facing up to the challenge of artistic formulae. It is a proof of the idealism of an artist trapped in an imagination-constraining life within a “small stabilization.”3

Translated from Polish by Anda MacBride

BIO

Krzysztof Skoczylas works at the interface between art and design disciplines. His interests include designing in the context of working of memory and recycling as an ecologically important element of creative activity. He is an author of exhibitions’ design, workshops, and space interventions for such institutions as Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, Fort Institute of Photography, Zwierciadło Foundation, Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, Museum of the City of Łódź, Wyspa Institute of Art, Dizajn Gallery BWA Wrocław, Studio Gallery BWA Wrocław, Bunkier Sztuki Gallery of Contemporary Art, Centre of Contemporary Art in Toruń, BWA Gallery on Tarnów, Muzeum Ziemi Lubuskiej in Zielona Góra, and Polish Institute in Berlin. He was a member of Warsaw's Scalpture Department of Academy of Fine Arts' building design team. He took part in preparations of Warsaw Housing Standard (Warszawski Standard Mieszkaniowy). He currently works on the project of rebuilding of Ujazdowski Castle’s office space. He runs his own architectural office in Warsaw.

* Coverphoto: Cycero bust. An alteration of Bertel Thorvaldsen's photo (Wikimedia Commons), Krzysztof Skoczylas.

[1] The information referring to the work of the Polish architects in the Middle East is taken from: Piotr Bujas, Łukasz Stanek, Postmodernizm jest prawie w porządku. Polska architektura po socjalistycznej globalizacji, Bęc Zmiana 2012. All "borrowed" fragments are stated by the footnotes.

[2] Július Koller quoted from the publication that accompanied the exhibition Eyes Looking for a Head to Inhabit presented at the Museum of Art in 2011.

[3] Information "borrowed" from the text Szał Kollera by Anna Miller, published in the magazine “Szum,” available online: http://magazynszum.pl/szal-kollera-w-muzeum-sztuki-nowoczesnej/, [accessed: 20 June 2018].